Advertising sugary cereals to children needs regulation, report says

By Carey Gillam

Food companies are continuing to push unhealthy cereals high in sugar content into the diets of young children through targeted television advertising despite pledges by leading companies to voluntarily regulate such advertising, according to a new analysis.

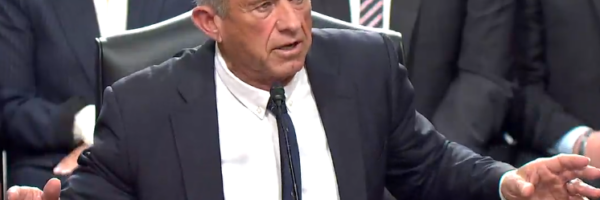

“Epidemic of chronic disease” spotlighted in Kennedy confirmation hearing

By Carey Gillam

America’s “epidemic of chronic disease” was spotlighted Wednesday in a contentious senate confirmation hearing for Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

Environmental and health programs thrown into chaos by Trump funding freeze

By Douglas Main

President Donald Trump’s surprise decision to freeze a massive portion of federal grants and loans — a move temporarily blocked by a federal court — has thrown environmental research, health programs, and community groups into chaos.

Upcoming Kennedy hearings to spotlight hotly debated public health issues

By Carey Gillam

Advocates for Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and his “Make America Healthy Again” agenda were gathered in Washington this week ahead of a senate committee hearing on Kennedy’s nomination to lead the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) – an event expected to put a spotlight on a number of hotly debated public and environmental health issues.

EPA proposal for pesticide tied to reproductive harm lands back with Trump

US environmental regulators are planning to change allowable levels of a weedkiller tied to reproductive health problems to a level critics say discounts years of documented health risks — and potentially marks a new battlefront within the Trump administration.

Amid series of rapid-fire policy reversals, Trump quietly withdraws proposed limits on PFAS

By Shannon Kelleher

Amid a flurry of actions curtailing Biden’s environmental policies, the administration of newly inaugurated President Donald Trump this week withdrew a plan to set limits on toxic PFAS chemicals in industrial wastewater.

Close to 30 million Americans face limited water supplies, government report finds

By Carey Gillam

Nearly 30 million people are living in areas of the US with limited water supplies as the country faces growing concerns over both water availability and quality, according to a new assessment by government scientists.

EPA moves to withdraw decision on paraquat, delays report on risks

By Carey Gillam

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is moving to withdraw its interim regulatory decision on paraquat, announcing that it needs more time to examine the potential health effects of the weed killing chemical that has been widely used in agriculture for decades, but also linked for years to the incurable brain ailment known as Parkinson’s disease.

Scientists cite disease “epidemic” in launch of new “Center to End Corporate Harm”

By Carey Gillam

Citing an “industrial epidemic of disease,” a group of scientists have launched an organization aimed at tracking and preventing diseases tied to pollution and products pushed by influential companies.

Lee Zeldin, Trump’s EPA nominee, pledges independence from industry ties in senate hearing

By Douglas Main

Incoming President Donald Trump’s nominee to lead the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) appeared on track for confirmation after a Senate hearing Thursday in which he pledged independence from industry money and influence.