California’s fight over cancer-causing drinking water contaminant

Bertha Magana has lived in the same house in rural Monterey County, California since 1987; it’s where she and her husband raised their four children, and the place they enjoy visits from their 11 grandchildren. Recently, however, 61-year-old Magana learned that the well from which the family gets its drinking water is contaminated with an industrial compound known to cause cancer. Her family is healthy, but Magana is now plagued with the constant worry that comes with knowing her water is unsafe.

“I am very worried,” Magana said in a recent interview, translated from Spanish by an interpreter.

Magana is one of millions of people living in the United States who rely on drinking water that is laced with hexavalent chromium, a toxic form of the metal chromium also known as chromium-6 or Cr(VI). And her fears reflect the concerns driving a battle in California between public officials, industry advocates and public health advocates, as the state is poised to become the first in the nation to set a drinking water standard for the contaminant.

Chromium-6 is used in stainless steel production, electroplating, and in the manufacturing of many products such as pigments in dyes, paints, inks, and plastics and other surface coatings. Contamination of drinking water sources can occur via industrial waste discharges and leaching from hazardous waste sites.

Several scientific studies, including by the U.S. National Toxicology Program (NTP), have shown that exposure to chromium-6 can cause cancer and other health problems. Workers in industrial settings are at risk, as are people drinking water contaminated with the compound, according to public health officials.

The popular 2000 film Erin Brockovich brought chromium-6 to national attention, featuring the true-life tale of a legal assistant who discovered links between elevated rates of cancer and death among residents of Hinkley, California, and the contaminant in their drinking water.

Despite the known risks, California regulators have struggled for decades over how to ensure the safety of drinking water across the state, particularly in small and poor communities where there are few resources for expensive, high-tech water treatment.

“It is frustrating that we, as the fifth largest economy in the world, can’t figure out a way to make sure people have tap water that is safe to drink,” said Kyle Jones, policy and legal director of the Community Water Center advocacy group. “We’ve known about it for so long and done nothing about it for so long. It is a carcinogen, and doing nothing for as long as we have is difficult to accept.”

A “public health goal”

In March, the California State Water Resources Control Board issued a draft report stating it was considering establishing a Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) at 10 parts per billion (ppb) for chromium-6 in drinking water provided by public water systems statewide. They said the MCL reflects a “primary emphasis on the protection of public health, and avoiding, to the extent technologically and economically feasible, any significant risk to public health.”

Under the proposed plan, water systems with more than 10,000 service connections would be required to comply with the MCL within two years of it being adopted, while systems with 1,000 to 10,000 service connections would be required to comply within three years, and smaller systems with fewer than 1,000 service connections would be given four years to come into compliance.

The proposed MCL is unchanged from one set in 2014 by the California Department of Public Health that was later invalidated by a state court ruling stemming from a lawsuit filed by the California Manufacturers and Technology Association. The association argued that the state had not evaluated whether or not compliance would be economically feasible.

The American Chemistry Council (ACC) also has opposed strict regulation of chromium-6 in drinking water, arguing on its website that there is no solid scientific evidence showing adverse health effects in drinking water at doses “likely encountered by humans.” The ACC says that the current U.S. drinking water standard for total chromium of 100 ppb is sufficiently protective, according to “extensive data.”

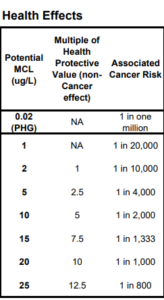

Several public health advocates say that a chromium-6 MCL at 10 ppb is not nearly protective enough as it is roughly 500 times higher than the Public Health Goal (PHG) of 0.02 ppb set in 2011 by the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessments (OEHHA).

They additionally point to the state water board’s own data showing the associated cancer risk is 1 in 2,000 at an MCL of 10 ppb, compared to 1 in 1,000,000 for the PGH of 0.02 ppb.

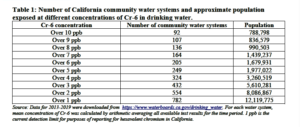

An analysis of California drinking water data conducted by the Environmental Working Group (EWG) found that roughly 11 million Californians who are exposed to levels of chromium-6 between 1 ppb and 10 ppb would see no required mitigation of their water systems, even though they would still be exposed to elevated cancer risks.

Chris Webb, a school teacher in a farming community near Watsonville, California, worries for his students’ health after school officials learned a few years ago that the water was contaminated and not safe to drink. Webb lives outside the area and can bring his own water to work each day. But for the students who live in the area, there is little escape from water sources that Webb believes likely also carry pesticides and other traces of farm chemicals.

“There are a number of carcinogenic issues we’re worried about here,” said Webb.

Nationwide concerns

While the focus is currently on California, worrisome levels of chromium-6 have been found at higher-than-recommended levels in drinking water that serves roughly 218 million people living in the United States, according to the EWG analysis.

Citing chromium-6 as well as other “known and emerging water contaminants,” U.S. Senator Tammy Baldwin (D-WI) last month introduced The Healthy Drinking Water Affordability Act, or The Healthy H2O Act, to provide grants for water testing and treatment technology directly to individuals, non-profits and local governments in rural communities.

Linda Birnbaum, former Director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and NTP, said setting standards for a contaminant such as chromium-6 is a complex matter because of requirements that standards be technologically and economically feasible. And the tighter the standards, the more costly and difficult required water treatment can be.

California officials have estimated that at the proposed MCL of 10 ppb, customers of some of the smallest water systems would see rate increases of approximately $40 per month. The total average annual costs per system is estimated to range from $82,711 to $15,865,599, depending on the system.

“That is what always drives it, is the cost,” Birnbaum said. “And rather than the polluter paying, it is the public who pays. I think the polluters should pay. If they polluted, why should the taxpayers have to pay to get rid of their mess?”

EWG

EWG

May 13, 2022 @ 4:39 pm

THANK YOU FOR PUBLISHING THIS NEWSLETTER. THIS TYPE OF IMPORTANT, INFORMATIVE, DATA IS RARELY AVAILABLE IN LOCAL OR NATIONAL NEWS OUTLETS UNTIL PEOPLE START DYING, AND THE DAMAGE IS DONE! THE WORK AND INFORMATION PROVIDED BY THE EWG ON THE NC DRINKING WATER SITUATION DUE TO CHEMOURS CHEMICAL COMPANY WAS THE PRIMARY REASON MY HUSBAND AND I CHANGED OUR MINDS ON BUYING A HOME IN NORTH CAROLINA & OPTED TO MOVE TO SOUTH CAROLINA INSTEAD! Thank You!