As farmers struggle with PFAS ‘forever chemicals,’ Maine races for solutions

For the past 18 years, Maine farmer Bill Pluecker has worked long hours tending to his family’s organic vegetable farm, growing crops he sells directly to consumers through a community agricultural program.

Working on the farm is a job that Pluecker juggles with his position as a state lawmaker, and the combination of roles gives Pluecker particular insight into a devastatingly broad environmental contamination problem farmers are facing throughout Maine, and around the United States.

The problem is PFAS. Often referred to as “forever chemicals” because they do not break down and can persist indefinitely, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) have become recognized as a significant health and environmental threat with broad reach. Researchers have found PFAS contaminating water, soil, food, and even the bodies of humans and animals around the world.

Widely used in consumer goods and industry since the 1940s, PFAS include more than 9,000 synthetic chemicals that build up in living tissue and can endanger health.

“It’s overwhelming; it’s in our products, in our bodies, in our food system,” said Pluecker, who is grateful that his own farm appears not to be contaminated with the PFAS he calls “poison.”

Types of PFAS chemicals have shown up in farm wells and farm soils from New Mexico and Colorado to Vermont, often due to PFAS runoff from firefighting foams at airports and military bases.

Pluecker has sponsored numerous bills to try to address PFAS problems in his state, including one signed into law in April called “An Act To Prohibit the Contamination of Clean Soils with So-called Forever Chemicals.”

Action is essential to stop PFAS from endlessly looping through soils, waters and waste streams, Pluecker said.

One recent estimate by the Environmental Working Group pegged U.S. cropland potentially affected by PFAS at 20 million acres.

Sludge a key issue

PFAS contamination in agriculture has been tied to a decades-long practice in which semisolid treated waste products known as biosolids, or sludge, are applied to farm fields. PFAS are used by a variety of industries to make such things as electronics, paints, fire-fighting foams, cleaning products and non-stick cookware.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) states that sludge can provide a range of benefits that include the addition of nutrients to the soil, and a reduced demand for synthetic fertilizers. The EPA estimates that half of biosolids nationally are applied to land.

However, PFAS contamination is surfacing on farms decades after just one or two sludge applications, in wells adjoining former sludge-spreading sites and in dairy milk due to hay grown on contaminated fields. In some cases, farmers themselves have PFAS levels in their blood typically associated with industrial exposure.

In 2016, a water utility in southern Maine monitoring for unregulated contaminants found two PFAS chemicals – PFOA and PFOS – in well water on a dairy farm. The Maine Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) traced the contamination to land applications on the site of both pulp and paper mill sludge and biosolids.

When the DEP began testing wastewater sludge in 2019, the agency found at least one PFAS compound in all the samples. A milk testing program begun that year soon identified a second dairy farm with high contaminant levels.

The new law in Maine bans the approval of sludge for land application unless it is first tested for PFAS and determined not to be harmful. The law is one of many steps taken by Maine to implement policy and regulatory changes and to test farm soils and waters for PFAS. Legislators also approved a $60 million fund to help address the agricultural impacts of PFAS, including further research, long-term site monitoring and direct farmer support. An additional $25 million has been allocated for the DEP to complete its initial PFAS site testing.

“Maine is not a rich state,” said Sharon Treat, senior counsel for the nonprofit Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy. “We’re devoting a substantial portion of what we have to root out this problem and that’s the right thing to do. But it’s hard when no one has your back.”

In 2021, the Maine Legislature adopted a PFAS drinking water standard of 20 parts per trillion for the sum of six PFAS compounds. Subsequently, the DEP found contamination over those levels at 191 wells or water sources near where paper mill sludge had been land-applied, and the state installed water filtration systems. The statewide count of contaminated wells has since risen to 310.

To limit PFAS entering the waste stream, Maine lawmakers passed the nation’s first phased-in ban of PFAS, eliminating its use in most products by 2030. By January 1, 2023, the law requires disclosure of products with intentionally added PFAS ingredients.

Maine legislators also mandated in 2021 that the DEP test soils and waters at more than 700 sites where spreading of sludge was permitted. The agency then posted a map of those sites.

EPA slow to act

PFAS chemicals remain largely unregulated at the federal level though it has been known for decades about serious health risks that PFAS pose, including an increased risk of types of cancer.

The EPA still supports “beneficial use” of biosolids as an agricultural fertilizer, despite a 2018 report from EPA’s Inspector General that characterized 61 potential constituents of biosolids as “acutely hazardous, hazardous or priority pollutants in other programs.”

Critics of sludge-spreading have long warned that it carries contamination risks, and organic certification does not allow for sludge applications.

Last year, President Joe Biden announced a multi-pronged federal plan to “prevent PFAS from being released into the air, drinking systems, and food supply,” and to expand clean-up efforts of existing contamination.

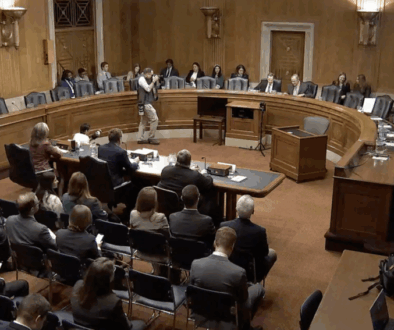

And in a recent U.S. House Agriculture Subcommittee meeting, Agriculture Secretary Thomas Vilsack suggested that more support might come through the Farm Bill slated for passage in 2023.

Some Maine advocates are skeptical, however.

“Most of the efforts are going to come from the state level,” said Patrick MacRoy, deputy director of the Maine nonprofit advocacy organization Defend Our Health. He said that agricultural impacts “will drive the discussion more than federal action.”

A lack of federal regulatory measures may continue hampering state efforts, said Richard Kersbergen, a University of Maine Cooperative Extension professor who has been researching the pathways of PFAS from soil into plants.

“It would benefit us if there was more federal guidance,” he said. “Maine is leading the way and that can be a difficult situation.”

(Editing and additional reporting by Carey Gillam)

June 7, 2022 @ 4:54 pm

To: Carey Gillam,

If you are a relative of Gail or Scott Gillam, whom I knew

while in college, I would just want them to know that Beth

Champagne is impressed with your work!

Best regards–