As “red tides” bloom, citizen scientists help map ocean danger zones

By Lena Beck

Nearly every day, Florida resident Pradeepa Siva goes paddle boarding through Doctors Pass in Naples. The thin passageway between Moorings Bay and the Florida Gulf of Mexico is home to a couple of friendly dolphins, which Siva often sees on her outings.

But the journey is about more than exercise and wildlife sightings, because when Siva paddle boards she is also participating in a government-funded science project aimed at protecting public health as climate change brings warming ocean waters and predictions for rising incidences of a dangerous phenomenon known as the “red tide.”

Red tides occur when warming waters and other factors spur the growth of a type of rust-colored algae known as Karenia brevis. The algae produces toxic compounds that are harmful to humans as well as dolphins, manatees, shellfish and other sea life. Exposure to the algae can cause respiratory illnesses and other problems for people who are exposed, and, in rare occasions, be debilitating or even fatal.

Siva knows how frightening it can be to be exposed to red tide. “You can’t breathe,” she said. “You start coughing — like choking, coughing.”

One of the largest red tide events in Florida was recorded in 2014, when water temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico surged to record highs and the harmful algae bloom stretched 90 miles long and 60 miles wide.

Another red tide outbreak that began in late 2017 persisted for 16 months, impacting Florida’s southwest, northwest, and east coasts at the same time.

The threat is not just to health: Scores of businesses were shuttered in multiple Florida communities along the state’s southwest coast due to the 2017-2019 red tide outbreak, with estimated losses in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

As ocean surface waters are forecast to continue to warm, potentially larger and more dangerous red tide events loom as well as blooms of other types of harmful algae. Toxic blooms have been seen in Australia, South Africa and Japan and coastal regions around the world now face the risk of “unprecedented diversity and frequency” of these events, according to the US National Office for Harmful Algal Blooms.

Though algae are important to sustain marine life, some algae produce toxins. When they overpopulate amid fast growth, they pose a definite public health risk. These blooms are not always red, but can also be blue or green. They can be found in freshwater as well as saltwater, and in Florida, peak season often occurs in late summer or early fall.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis has set up a red tide task force and the state has allocated more than $40 million since 2019 to addressing red tide.

Citizen scientists

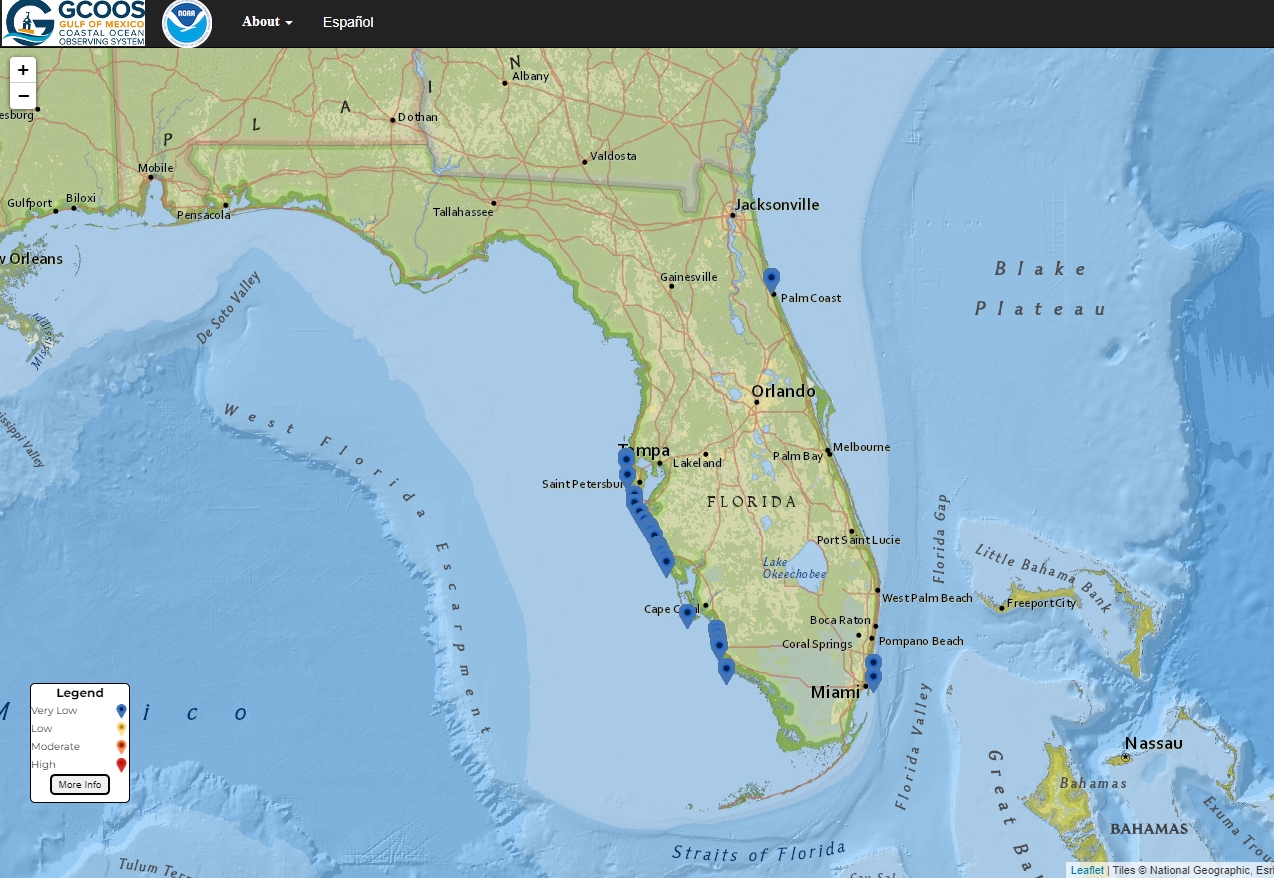

In an effort to address the threat, last year the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) launched the Red Tide Respiratory Forecast, an online map that shows the presence and severity of red tide at select locations. People can use the map to check safety conditions before swimming or fishing or engaging in other activities in the water. The warning system is especially important during peak bloom season from August to December.

The project is operated as a partnership between NOAA and the Gulf of Mexico Coastal Ocean Observing System (GCOOS), the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission-Fish and Wildlife Research Institute (FWC-FWRI) and Pinellas County Environmental Management.

The project is part of a nationwide effort to improve monitoring of, and response to, harmful algal blooms along US coasts.

“The need was clearly there, because people were getting sick,” said Richard Stumpf, NOAA oceanographer and principal investigator for the Red Tide Respiratory Forecast, which transitioned from an experimental project to fully operational last year. “And businesses were hurt badly.”

The forecast tool looks to a community of citizen science volunteers such as Siva who collect water samples from the ocean to contribute to the database. Last year, more than 5,400 water samples were uploaded by volunteers from 89 different sites.

“We don’t yet have every beach every day, which is our goal,” Stumpf said. “But we can potentially achieve that with the volunteers. That’s a huge, huge advantage to having those community volunteers.”

For Siva, the work is relatively simple: She bring two small vials with her when she paddle boards, collecting samples of seawater. When she gets home, Siva pours the samples onto a slide for a portable microscope. The device connects to an iPod, which Siva uses to take a 30-second video of each sample. She then upload the videos to a central server that automatically analyzes the footage for the presence of the toxic algae.

Expanding for Spanish speakers

The danger associated with bloom conditions can vary dramatically hour to hour, and beach to beach, making frequent, hyper-localized data like that of the Red Tide Respiratory Forecast essential to protect public health, scientists say.

Until this year, the Red Tide Respiratory Forecast was only presented in English, but recently was made available in Spanish in recognition of growing diversity in the area.

“The translation is a recognition that there are large communities in South Florida that are more fluent in Spanish than in English,” Stumpf said.

Nearly a quarter of Florida’s population are native Spanish speakers, and as red tide monitoring technology continues to evolve and improve, advocates say that it is essential to make this critical public health information accessible to these communities. The Florida Department of Health has information about red tide on their website — but still only in English.

Maria Revelles, director of the Chispa Florida environmental justice organization, said government-backed tools such as the red tide map need to be more accessible to non-English speaking populations.

“I think that the conversation is limited, and especially absent in minority communities,” Revelles said. “We need to talk to Black and Brown communities, because they are the ones that are hit every day, so they are the ones that probably have answers,” Revelles said.

The NOAA red tide mapping project is similar to a program in Sweden launched in 2005 to monitor for cyanobacteria blooms around the popular resort island of Öland in the Baltic for about a decade.