OIG probe finds EPA broke the rules in pesticide cancer evaluation

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) did not properly conduct the cancer risk for a widely used pesticide, a failure that could jeopardize human health, the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) said in a report issued this week.

In its July 20 report, the OIG cited a number of problems with how the EPA evaluated the cancer risk of the soil fumigant 1,3-Dichloropropene, (1,3-D). Among other problems, the EPA did not adhere to standard operating procedures and federal requirements in doing the assessment, the OIG found.

“These departures from established standards during the cancer assessment for 1,3-D undermine the EPA’s credibility, as well as public confidence in and the transparency of the Agency’s scientific approaches, in its efforts to prevent unreasonable impacts on human health,” the OIG said of the EPA.

1,3-D is one of the top three soil fumigants used in the United States. From 2014 through 2018, an average of approximately 37 million pounds of 1,3-D were applied to an average of 300,000 acres of agricultural crops annually.

The OIG probe came after the EPA changed the cancer classification in 2019 in a way that essentially downgraded the cancer risk and allowed for vastly increased exposures.

The OIG explained in its report:

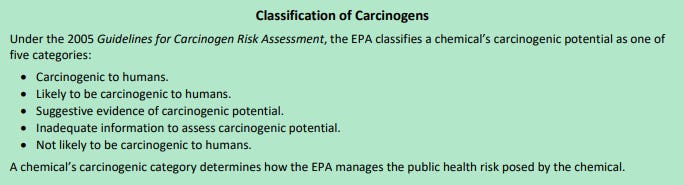

“From 1985 through 2018, the EPA classified 1,3-D as “Likely to be Carcinogenic to Humans,” which means that there is evidence of carcinogenic potential in two or more different species, sexes, or strains, or from two or more different sites or exposure routes. With this classification, the EPA quantified 1,3-D’s cancer risk, which was used to identify acceptable exposure levels, at the one-in-10,000 excess lifetime cancer risk level, meaning that if 10,000 people are exposed to the same concentration of this chemical over an estimated lifetime, one additional person would likely develop cancer from this exposure. In 2019, the EPA changed the classification for 1,3-D to “Suggestive Evidence of Carcinogenic Potential,” which means that there is evidence of tumors in only a single animal cancer study or only at a single dose. With this classification change, the EPA does not quantify the chemical’s cancer risk and establishes acceptable exposure levels based only on noncancerous effects. The cancer reclassification of 1,3-D allows the long-term exposure level considered an unreasonable risk to humans to increase 90-fold.”

The OIG said that in conducting its cancer-assessment for 1,3-D, the EPA falsely declared that “no studies were identified as containing potentially relevant information,” while the OIG easily found more than 100 relevant studies on 1,3-D.

“Without a thorough, comprehensive literature search, the EPA neglected to review all health-effects data and potential adverse effects on human health,” the OIG said in its report.

“The EPA’s resulting cancer classification downgrade could lead to significant increases in exposure levels to humans and affect the pesticide’s application rate and level of personal protective equipment required by applicators,” the OIG said. “The EPA needs to take action to improve the scientific credibility of and bolster public trust in the Agency’s 1,3-D decision.”

The OIG said it initiated the evaluation after multiple complaints were submitted to the Office of Inspector General Hotline.

The findings echo complaints that numerous critics have made for years about the EPA’s assessments of a number of pesticides and other chemicals.

The report follows a recent ruling by the 9th U.S Circuit Court of Appeals that found the EPA’s 2020 assessment of glyphosate, the active ingredient in Monsanto’s Roundup herbicide, was flawed in many ways. The EPA applied “inconsistent reasoning” in finding that glyphosate does not pose “any reasonable risk to man or the environment,” the court ruled.

The court vacated the human health portion of the EPA’s glyphosate assessment and said the agency needed to apply “further consideration” to evidence.

The EPA’s assessment that glyphosate is “not likely” to be carcinogenic to humans has been a key defense for Monsanto and its owner Bayer AG in litigation brought by people who allege they developed non-Hodgkin lymphoma due to exposure to glyphosate-based herbicides.

Last year, The Intercept revealed whistleblower allegations brought by a group of EPA scientists who alleged EPA management tampered with the assessments of dozens of chemicals to make them appear safer than they were.

EWG

EWG