Postcard from California: Close California’s last nuclear power plant

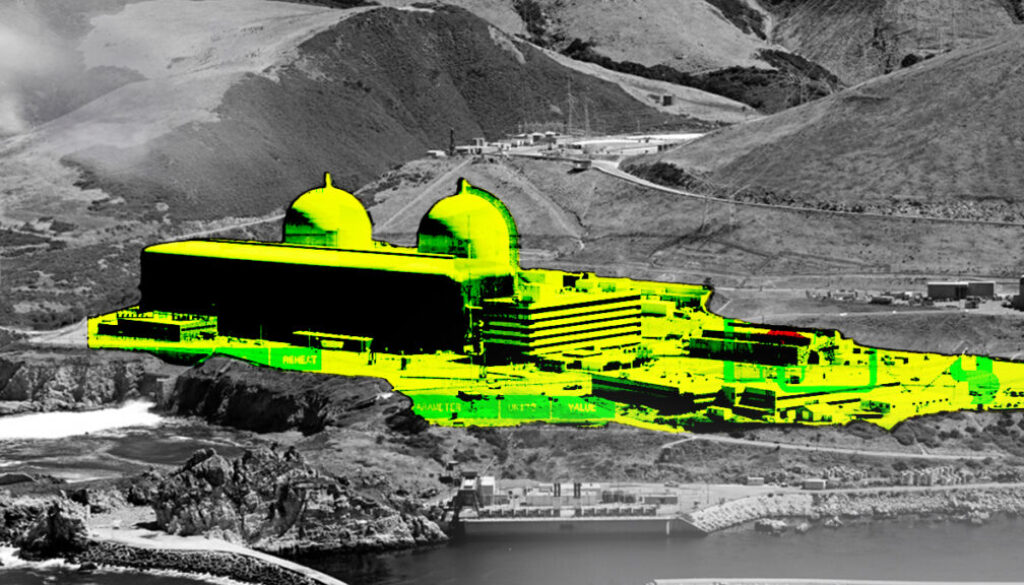

The last nuclear power plant in California, vulnerable to earthquakes and priced out of the energy market by cheaper renewables, is slated to close in three years.

But now both Gov. Gavin Newsom and the Biden administration, citing the specious notion that nuclear power is needed to help address the climate crisis, are poised to give the plant’s owner billions of taxpayer dollars to keep it open. It’s a really bad idea.

It was 1961 when Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E) unveiled plans for the first US commercial-scale nuclear plant on the Pacific Coast north of San Francisco. PG&E initially aimed to open a reactor on Bodega Head, a breathtaking peninsula near the village where Alfred Hitchcock later would film “The Birds.”

But a Navy geophysicist discovered a previously unknown arm of the San Andreas Fault ran through the peninsula, an unsettling find considering the fact that the San Andreas Fault triggered the earthquake that nearly leveled San Francisco in 1906.

PG&E settled on a new site 300 miles south, in the bucolic Diablo Canyon near the town of San Luis Obispo.

PG&E broke ground for the first of Diablo Canyon’s twin reactors in 1968. Seven months later, Shell Oil engineers discovered the Hosgri Fault a few miles offshore. Astoundingly, the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission allowed construction to continue. Since the reactors went online in 1985 and 1987, three other nearby fault lines have been found, nearly encircling the plant.

Decades of revelations about earthquake danger at Diablo Canyon have been punctuated with coverups, whistleblower scandals and reckless disregard by federal and state regulators.

Finally, in 2016, PG&E announced it would not renew the reactors’ operating licenses beyond their expiration in 2024 and 2025. The company said plummeting costs of solar and other renewable sources meant nuclear power could not compete in the energy market of the 21st century.

A study by Friends of the Earth found replacing Diablo’s output with renewables would save PG&E customers $2 billion to $5 billion. (I was a consultant to FOE’s campaigns to close Diablo Canyon and Southern California Edison’s San Onofre nuclear plant, which shut down in 2013. The state once had four nuclear plants.)

Falling behind

But California has since fallen behind on its goals for cutting greenhouse gas emissions. Independent researchers calculate that to achieve “net-zero” carbon by 2045, emissions must be cut at two to three times the current rate.

Unlike power plants that burn coal or natural gas, nuclear plants don’t directly emit greenhouse gases. (Emissions from uranium mining, plant construction and the handling of radioactive waste belie the claim that nuclear plants are “carbon-free,” and they need frequent refueling, so they’re not “renewable energy.”) Diablo supplies less than one-tenth of California’s electricity, and if that’s replaced by burning fossil fuels, emissions could rise, and the state could fall farther behind.

That’s the line pushed by the nuclear industry and its apologists, trying once again to stay alive by touting a “nuclear renaissance.” And once again, many politicians are falling for it.

In 2016, Newsom, then lieutenant governor and head of the state lands commission, voted to close Diablo. US Sen. Dianne Feinstein agreed. But two months ago Feinstein said she had changed her mind.

And the governor unveiled a draft bill that would give PG&E a $1.4 billion forgivable loan to keep the plant open 10 more years. The bill, which would also exempt the extension from environmental rules opponents could use to challenge it, could pass before the legislative session ends Aug. 31.

Even more taxpayer money might flow to PG&E. In April, the Biden administration launched a $6 billion program to bail out nuclear plants slated for closure. Because Diablo is state-regulated, it seemed ineligible, but the Newsom administration asked the Department of Energy to change the rules. DOE has yet to decide, but if permitted, PG&E plans to apply for funds. (It’s unclear how the potential California loan could affect PG&E’s eligibility for the federal bailout.)

How much would it cost to keep Diablo Canyon open?

A recent study for a pro-nuclear group said renewing the reactor licenses and making necessary upgrades could cost $2 billion. But the study admits that could be underestimating the cost of new state-mandated cooling towers needed to protect fish and marine mammal habitat from the reactor-warmed seawater Diablo discharges into the Morro Bay State Marine Reserve.

“Plain stupid”

Rochelle Becker, executive director of the San Luis Obispo-based Alliance for Nuclear Responsibility, a party to the agreement to shut the plant, said keeping Diablo open would be “hamstringing the renewable revolution.”

“Nothing has changed since 2016,” Becker said. “Diablo Canyon’s energy is still too expensive, the seismic questions remain unresolved, and the costs to upgrade the deferred maintenance… are unknown. We intend to push forward with our goal of seeing Diablo Canyon retired for good by 2025.”

In a media briefing, clean energy consultant Robert Freehling said adoption of rooftop solar and other measures have already significantly cut harmful emissions and more reductions are forecast before 2025, reducing the need to keep Diablo open.

Freehling, who has consulted for the Sacramento Municipal Utility District, which closed its Rancho Seco nuclear plant in 1989, asked: “How many times do we have to (reduce the potential emission savings of keeping Diablo Canyon open) before we, as a state, acknowledge that we’ve already replaced it?”

Another consideration: For every year a nuclear plant operates, it generates reactor waste that remains dangerously radioactive for tens to hundreds of thousands of years. More than 90,000 tons of waste are stored at reactor sites nationwide, including waste from Diablo Canyon.

Shaun Burnie, a nuclear expert with the Greenpeace advocacy group, saw the impacts of the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan, and recently returned from Ukraine, where he investigated radioactive contamination at the site of the 1986 Chernobyl meltdown.

“The idea that in an active earthquake zone, you will continue to try to safely operate reactors that will generate waste that remains hazardous for many thousands of years is dangerously irresponsible and plain stupid,” Burnie said in a phone interview from his home in Scotland. “This has nothing to do with saving climate – it’s just the nuclear industry grasping for yet another life raft.”

Record of disaster

Californians should be sick at the idea of giving money to PG&E. The company claims “nothing is more important than safety,” but its record of disaster tells another story.

PG&E was convicted of six felonies related to lax maintenance that caused the 2010 explosion of a gas pipeline that killed eight people. Rusted transmission equipment sparked the 2018 Camp Fire that killed 85 people and destroyed the town of Paradise. And PG&E’s power lines have since been linked to three more megafires, which have killed five people and burned hundreds of thousands of acres.

How can California justify giving taxpayers’ money to a criminally negligent company that for 117 years has held a state-sanctioned monopoly over a vast territory and whose unceasing rate hikes have helped drive the state’s electricity rates to the second highest in the country?

In 2015, years before the catastrophic wildfires, the state’s top utility regulator said PG&E lacked “a safety culture” and could be too big “to succeed at safety.” In 2019, Newsom himself said PG&E could not be trusted after being “caught red-handed over and over again, lying, manipulating or misleading the public.”

Newsom should listen to his own words. California should be working to break up PG&E – not prop it up by extending the life of a dangerous nuclear power plant that should never have been built.

Bill Walker has more than 40 years of experience as a journalist and environmental advocate. He lives in California’s San Joaquin Valley.

(Opinion columns published in The New Lede represent the views of the individual(s) authoring the columns and not necessarily the perspectives of TNL editors.)