Bill bans deep-sea mining in California waters

California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a bill this week that will prevent deep sea mining in the waters off the state coastline, a move that joins California with other western states in a bid to protect more than 2,500 square miles of Pacific Ocean seafloor.

Deep sea mining involves the retrieval of minerals and deposits from the ocean floor found at depths of 200 meters or greater. Critics say the practice can damage ocean ecosystems and pollute the water with destructive plumes of sediment that can harm sea life, but advocates say the practice is critical to meeting demand for minerals used in making an array of products.

“We know incredibly little about what’s in our ocean,” said Matthew Montgomery, a spokesman for state lawmaker Luz Rivas, who authored the bill. “But while we don’t necessarily know what’s on our ocean floors, we know how destructive this practice [of deep sea mining] can be.”

The California Seabed Mining Prevention Act aims both to protect ocean ecosystems and California’s economy. Valued at $45 billion and employing over half a million people, California’s ocean-based economy is the largest in the United States and includes tourism and recreation.

“I think it’s a precedent-setter,” said Arlo Hemphill, a Greenpeace USA expert on deep sea mining. “There are whispers that Hawaii might do something similar. If enough states do this, it sends a message to Washington that we need something like this at the federal level.”

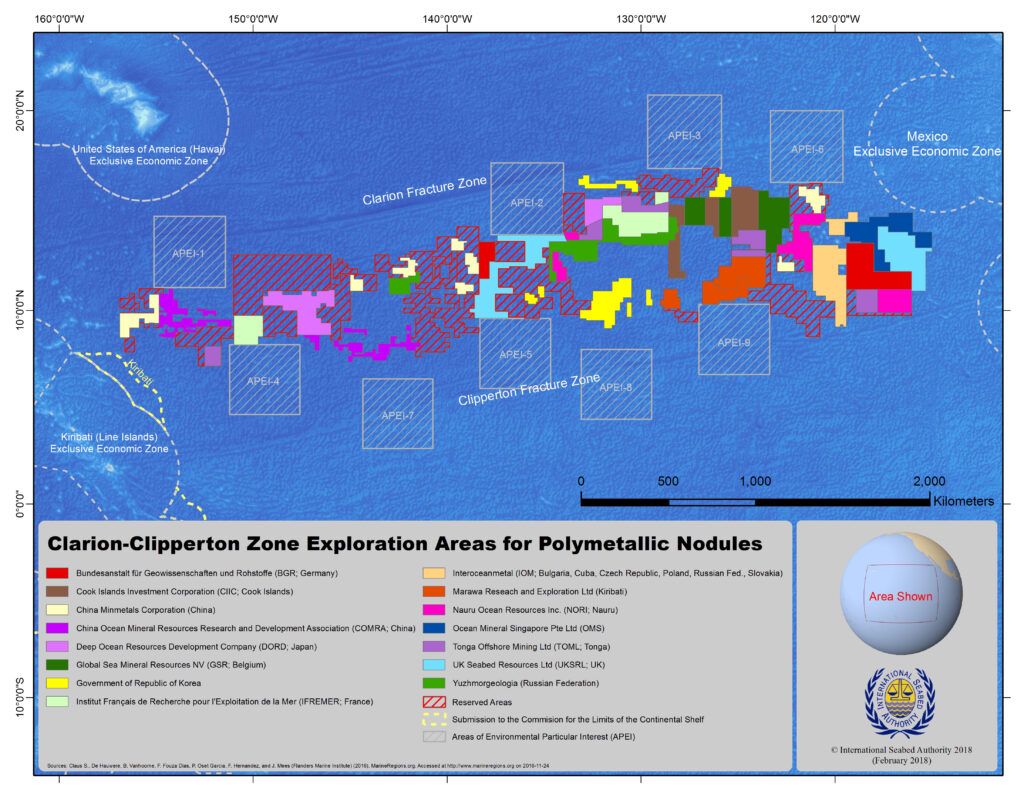

The new law does not stop foreign companies from staging their vessels at California docks. Last year, a Belgian company staged its ship in the port of San Diego before setting out to test mining equipment in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), an area between Hawaii and Mexico popular with seabed mining companies.

The CCZ is home to an abundance of rocks called polymetallic nodules, which contain metals that can be used to make batteries for electric vehicles.

California’s bill was signed just days after a mining ship departed from a port in Mexico to conduct what amounts to a dress rehearsal for commercial mining in the CCZ. A group of independent researchers are monitoring its environmental impacts.

The International Seabed Authority approved the test earlier this month despite a vote overwhelmingly in favor of a moratorium on deep sea mining last year at the world congress of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Laundry list of concerns

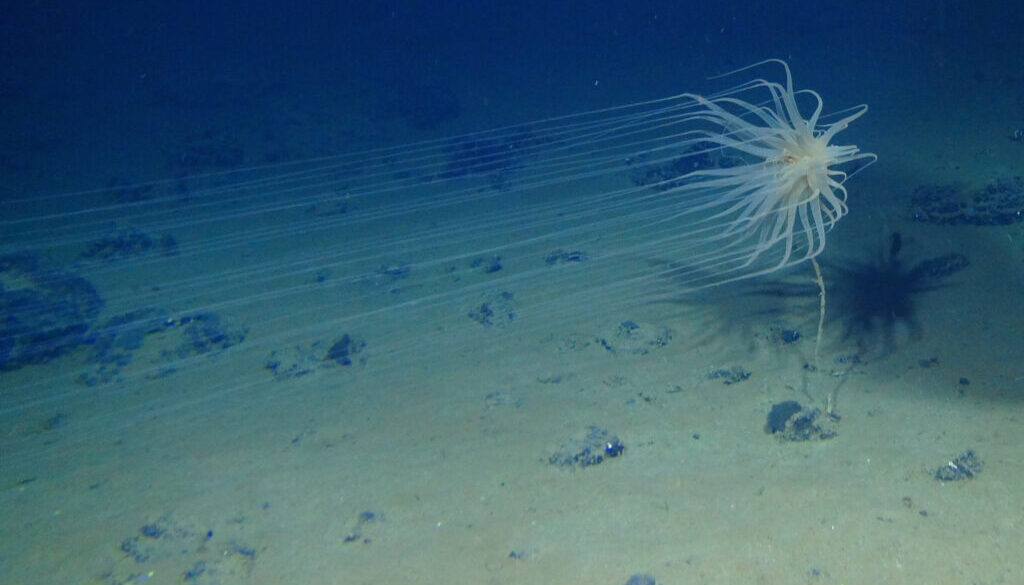

Deep-sea mining comes with a laundry list of environmental concerns. More than half of deep-sea creatures in the CCZ, including the enigmatic ghost octopus, depend on the nodules companies want to harvest, which take millions of years to form and could trigger a “cascade of negative effects on the ecosystem” if removed, according to a study by the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology.

Sediment plumes could potentially travel many miles, impacting commercially important fish. And some scientists are concerned that the practice may exacerbate climate change by stirring up carbon-containing sediment sequestered on the seafloor

“These are all unanswered questions we might find out the hard way by just doing it,” said Hemphill.

An April 2022 assessment of the science on managing deep-sea mining’s environmental impact concludes: “There are few categories of publicly available scientific knowledge comprehensive enough to enable evidence-based decision-making regarding environmental management, including whether to proceed with mining in regions where exploration contracts have been granted by the International Seabed Authority.”

A new study published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances offered some novel insights into deep-sea mining’s environmental impact. The study reports findings from a 2021 research cruise to the CCZ, where a pre-prototype collector vehicle cruised the seafloor at a depth of 4,500 meters, measuring the sediment cloud it produced.

The study revealed that the sediment plume stayed relatively close to the seafloor rather than quickly rising into the water column as expected.

“The big takeaway is that there are complex processes like turbidity currents that take place when you do this kind of collection,” study co-author Thomas Peacock, professor of mechanical engineering at MIT, said in a press release. “So, any effort to model a deep-sea-mining operation’s impact will have to capture these processes.”

(Featured image by Craig Smith and Diva Amon, ABYSSLINE Project/ NOAA. A Relicanthus, a newly discovered species in the CCZ, lives on sponge stalks attached to nodules.)