Utah tribe wants polluting uranium mill closed

This Saturday the Ute Mountain Ute tribe in southeastern Utah is planning a rally to protest the last functioning uranium mill in the United States. The tribe says the White Mesa Mill, which sits on sacred ancestral tribal lands, has been polluting the environment and jeopardizing the health of local communities for decades.

“We keep fighting and fighting to get it to either shut down or get it to move,” said Michael Badback, a tribal member and longtime White Mesa resident.

More than 700 million pounds of radioactive waste from across the US are buried in the White Mesa Uranium Mill’s waste pits, according to a report by Grand Canyon Trust. And the site may soon become a dumping ground for radioactive materials from around the world, with waste streams from Canada, Japan, and Europe approved for shipment to the mill.

While the mill was designed to accept crushed uranium ore from mines, it can also accept waste streams as long as they contain uranium or thorium.

“Really what we have is a uranium mill that’s essentially functioning as a low-level radioactive waste disposal facility without being regulated like one,” said Tim Peterson, cultural landscapes director at Grand Canyon Trust. “It’s accepting this sort of stew or cocktail of materials that has all kinds of other components in it. We don’t have any other facility in the United States that has this particular mix in its waste pits, so we don’t really know how these things interact and what they might do together.”

If the mill were to meet the requirements of a low-level radioactive waste disposal facility, Peterson said it would need to follow a much more stringent regulatory process that would prohibit it from operating so close to the community, noting that some community members live less than 2.5 miles from the mill’s radioactive tailings cells.

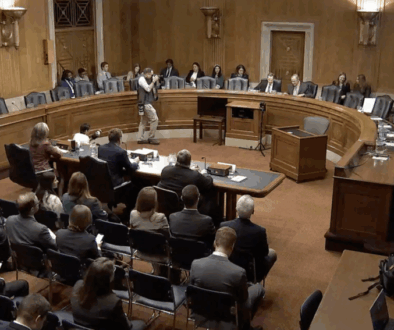

Last year, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) determined that the mill was in violation of the Clean Air Act, with one of its waste ponds not properly covered with water to reduce toxic radon emissions. A flight over the mill in July by the organization Ecoflight suggests a second pond may also be exposing hazardous materials.

A concerned community

In a proposed land management plan for Bears Ears National Monument, which is located about a mile from the plant, the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition wrote that air and water pollution from the mill are “directly affecting the local communities.” The coalition also expressed concern that toxic dust falling on local plants could pose cancer risks for tribal members who use them for food or medicine.

“This development causes a drastic change to the natural environment, but often it is only the start of the damage to the environment that may persist for generations,” said the coalition. “There is a sentiment among some Native residents in the region that southeast Utah is viewed as a money-making place for non-Native Utah residents. Concerns have been expressed that the non-Native people are not thinking of the future.”

Badback recalled how the world around him has transformed in the decades since the mine began operating.

“As a teenager, we used to hunt all over Black Mesa. We don’t have rabbits anymore, the cottontails we used to hunt and eat for winter. Our sagebrush is all dry near the mill. [In the past,] even during droughts they were still nice and green, almost a turquoise color. But now they’re not. When the wind blows, whatever crystals from the ponds that aren’t filled come down this way.”

Contaminants including nitrate and chloroform have been detected in the groundwater under the mill (the mill’s owners argue this happened before the mill was built). Badback and other White Mesa residents are concerned that waste from the mill may contaminate the aquifer that supplies local drinking water, too. When Badback runs the faucet, the water gives off a bad smell and leaves a rust color in the bathtubs and sinks.

“We just use it for our livestock, our animals and the trees,” he said. “We don’t drink it. We have to go an hour and a half just to buy water.”

He also worries about his grandson and other children who have to ride the school bus past the mill every day.

“A lot of our kids, they don’t play outside anymore like they used to,” said Badback. “Some of them have asthma now.”

The Ute tribe recently received an EPA grant to design an epidemiological study that will investigate ties between the mill’s activities and the community’s health problems.

Still operating

But while the area tribal residents worry about the health impacts of the plant operations, Energy Fuels, the company that owns the mill, is seeking to grow. The mill is accepting monazite ore left over from mining operations in the Southeast, extracting a mixed rare earth carbonate, and sending it to a facility in Estonia. The finished product is used in electronics.

Energy Fuels hopes to develop the capability to separate out individual rare earth elements from the carbonate concentrate onsite. However, Sarah Fields, a program director at Uranium Watch, recently questioned the legality of this move.

“The rare earth element line of business there is just to keep [the mill] operating even longer,” said Peterson. “When it was built and licensed, the original intention was to have it operate for 10 to 15 years and then have it clean up and shut down. Now, [over] 40 years later, it’s still operating.”

“We are deeply committed to addressing the world’s most pressing environmental issues, while advancing toward the electrification of the world economy,” said Energy Fuels in a 2021 news release. “Energy Fuels has and continues to be profoundly committed to responsible and modern mining and production, and all US uranium and [rare earth elements] production is done to the highest global standards for environmental protection and human rights.”

(Photo by Tim Peterson. A July 2022 Ecoflight shows a waste pit at White Mesa Mill that appears not to be properly covered.)