Farmer safety net growing more costly as climate changes

As cool weather sets in to the US Midwest, much of the farm state of Iowa is suffering from moderate to severe drought, but for farmer Brent Drey, another worrisome weather trend is also top of mind: Over the past few decades, the Drey family farm has noticed an uptick in rainfall, which often comes down so hard and fast that the moisture actually does more harm than good.

“There are times, especially in the spring, where it can dump three or four inches in a matter of an hour or two,” Drey said. “That really makes a mess for any farmer.”

Drey Farms, which grows 3,000 acres of mostly corn and soybeans near Sac City, Iowa, has sometimes lost production due to excess moisture, according to Drey. Flooding, heavy rains and excess snow melt can complicate planting, and drown out or sicken maturing crops as wet conditions lead to elevated levels of mold, fungus, and toxins.

For Drey and other farmers who suffer production losses due to excess moisture, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) has long offered a crop insurance program to cover their losses.

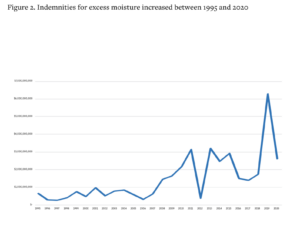

But an analysis released last month by the Environmental Working Group (EWG) shows that this safety net is growing increasingly more costly: excess moisture-related crop problems triggered $12.9 billion in insurance payments to Midwest farmers between 2001 and 2020. In 2008, payouts for excess moisture in the region totaled a little less than $1 billion, but by 2019 the payouts totaled closed to $3 billion, the analysis shows.

Climbing payments

Overall, those crop insurance payments for excess moisture problems have risen almost 300% from 1995 to 2020, according to the USDA’s Risk Management Agency, which runs the crop insurance program. The climbing payments come as annual precipitation in the region has grown.

According to a report by the US Global Change Research Program, over the past 30 years, increased rainfall from April to June in the Midwest has been the “most impactful climate trend for agriculture.”

“The climate crisis is already driving up costs of the program for both taxpayers and farmers,” said Anne Schechinger, an EWG farming and agriculture expert who authored the analysis.

The EWG report, which analyzed data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, found that 683 of the 738 counties in Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Ohio and Wisconsin, had rising annual county-level precipitation between 2001 and 2020.

In the same period, 661 of those counties with rising precipitation also received crop insurance indemnity payments from the federal crop insurance program for problems caused by excess moisture. According to the report, the excess moisture payments accounted for about one-third of all crop insurance payments made in those counties.

Since 1958, the Midwest has seen a 42% increase in the amount of total annual precipitation that has fallen in the most extreme events. Climate projections for the Midwest predict the trend to continue.

Climate change has also caused a shift of precipitation events to winter and spring, rather than summer, said Barbara Mayes Boustead, a climatologist at the National Weather Service. Frozen ground, combined with large amounts of snowmelt and a lack of vegetation in spring, compound with heavy rainfall events to make precipitation especially difficult to deal with.

Drey said the increased heavy rain events had carved new gullies and ravines into the landscape around his farm. In the spring of 2019, the fields were so soggy that Drey had to order a special tow rope to pull tractors out of the mud. Elsewhere in the region that year, floods washed out entire fields of crops.

“Dysfunctional”

Some industry experts are calling for the USDA’s crop insurance program to be restructured in ways that incentivize farmers to adopt new farming practices that could help mitigate losses associated with excess moisture as well as cycles of drought and other climate-related impacts.

The current system is “dysfunctional” and will eventually become “untenable,” as the climate continues to change, said Silvia Secchi, a natural resource economist at the University of Iowa.

Farmers should be planting cover crops, increasing the amount of land used for vegetation buffers, diversifying crops, and introducing pasture systems for livestock, among other measures, she and other experts say.

According to the USDA, less than a quarter of US farms currently practice sustainability techniques.

Another way to restructure the crop insurance program would be to expand the types of crops that are able to receive these subsidies, said Secchi. That would mean a farmer would receive subsidies for crop insurance for a broader array of land uses. Making certain conservation practices a prerequisite for farmers to be part of the federal crop insurance program could be an effective policy change, too, as well as ending insurance payments for crops grown on land most vulnerable to flooding, she said.

“If they didn’t receive the subsidy, people wouldn’t farm there,” said Secchi.

(Featured photo: Aftermath of the 2019 Midwest flooding at the Offut Air Base south of Omaha, Nebraska. Credit:U .S. Air Force, TSgt. Rachelle Blake).