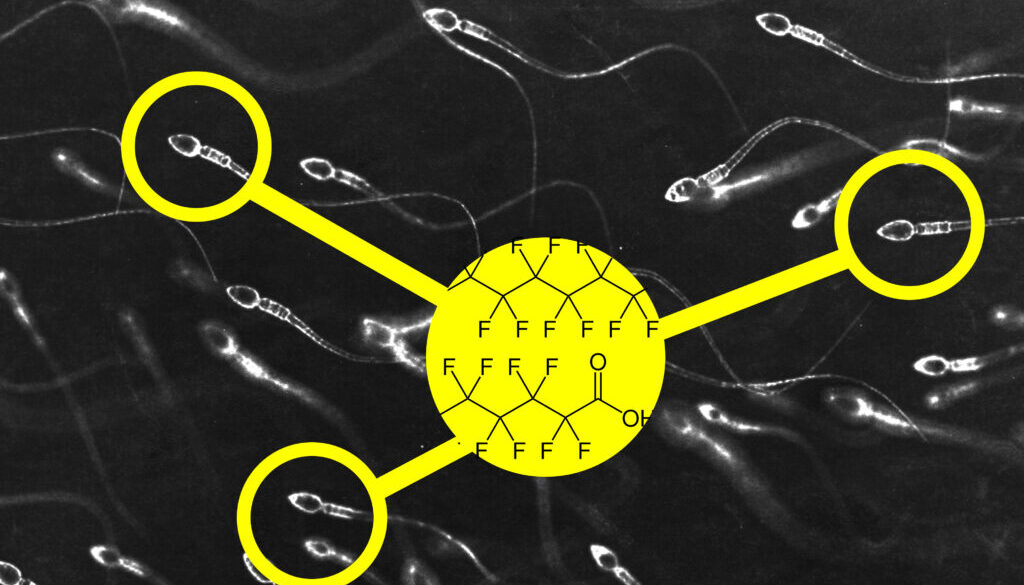

Pregnant mothers’ PFAS exposure may affect adult sons’ sperm quality

Exposure to toxic PFAS chemicals during pregnancy potentially can affect the reproductive health of male children after they reach maturity, researchers reported last month.

In a study that included more than 800 young Danish men, researchers found associations between lower sperm quality when the men reached young adulthood and levels of PFAS in their mothers’ plasma during early pregnancy.

The findings, which were published October 5 in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives, suggested that combined maternal exposure to seven of these toxic “forever chemicals” was associated with male offspring who grew up to have lower sperm concentrations, lower total sperm counts, and higher proportions of sperm that cannot travel normally (or at all).

The scientists identified one particular PFAS, perfluoroheptanoic acid (PFHpA), as the main contributor to all three effects on sperm quality, although they caution that more research is needed to confirm whether the chemical really has an outsized effect.

“This could mean that PFHpA is very potent or has a higher placental transfer than the other PFAS,” said Sandra Søgaard Tøttenborg, a professor at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark and an author of the study. “It could also be a chance finding, considering the multiple comparisons we’ve made and the low concentrations of PFHpA. Before we have other studies to compare with and a more evidence on the mechanisms, we don’t put too much emphasis on this finding.”

Global fertility decline

Male sperm count and quality are generally on the decline. A 2017 analysis showed a 50-60% decline in sperm concentrations in men from around the world from 1973 to 2011, while a 2019 study found that the proportion of men in two countries with a normal number of motile sperm dropped by about 10% from 2002 to 2017.

Pheruza Tarapore, an environmental and public health sciences researcher at the University of Cincinnati who was not involved in the study, thinks that endocrine disruptors including bisphenol A (BPA), bisphenol S (BPS), and PFAS may help explain this concerning phenomenon.

“I think exposures to all these chemicals probably contributes to this decreased fertility we are seeing,” she said.

But while exposure to PFAS has been linked to increased risk for cancer, as well as numerous other health impacts, and previous studies have found that these chemicals interfere with the female reproductive system, it has remained unclear whether PFAS affect male reproductive function.

Tøttenborg noted that previous studies examining fetal exposure to PFAS and offspring fertility only looked at the impact of two of the thousands of PFAS chemicals, PFOA and PFOS, and examined exposure later in pregnancy.

PFAS and sperm quality

To investigate the effects of a greater sample of PFAS chemicals, Tøttenborg and colleagues analyzed the sperm quality of 864 Danish men ages 18 to 21 from a cohort established between 2017 and 2019. The researchers retrieved plasma samples taken from the men’s mothers during primarily the first trimester of pregnancy, which had been stored in the Danish National Biobank. When they measured levels of 15 PFAS in the samples, they found seven with detectable levels across more than 80% of the samples and included these in the analysis.

Tøttenborg and colleagues found that each one-unit increase in maternal exposure to these combined seven PFAS during pregnancy was associated with an 8% reduction in sperm concentration when the male offspring reached young adulthood, as well as a 10% reduction in sperm count and a 5% higher proportion of sperm incapable of normal motility.

However, the researchers did not find a clear association between maternal exposure to PFAS during pregnancy and testicular volume or reproductive hormones.

“We have taken into account many factors that may confound/confuse the results such as maternal smoking,” said Tøttenborg. “We have used state-of-the-art techniques to analyze the PFAS and semen quality, and by design we have long temporal separation between exposure and outcome.”

Tøttenborg noted that the study focused primarily on long-chain PFAS, which are being phased out and replaced with short-chain PFAS. While these next-generation chemicals have been touted by industry as safer alternatives, research has found they are also quite toxic.

“We need more studies on the short-chain PFAS to say anything about them,” said Tøttenborg. “Based on what we found – and what we’ve seen in other studies – I believe there is good reason for concern.”