Antarctic conservation strategies are “insufficient” to protect the bulk of species, study says

Current conservation efforts under the provisions of a major international treaty to protect the Antarctic are “insufficient” to halt population declines of most Antarctic life, according to a new study. However, scientists note that there are low-cost strategies that could more effectively protect the continent.

The study, which was published today in the journal PLOS Biology, found that unless more intensive conservation efforts are undertaken by the global community, population declines will continue for approximately 65% of terrestrial species and seabirds that call Antarctica home. Despite protections from the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, which has been in effect since 1998, emperor penguins are at particularly high risk of population decline, followed by a species of nematode worm, Adélie penguins, and other seabirds. Authors of the study write that conservation of Antarctic species is key for developing new technologies or medicines, and for protecting the continent itself, which provides “essential ecosystem services” like regulating the global climate.

“Antarctica is not safe from global threats. It’s not as safe as we thought it was. And we need global action to help save it,” said Jasmine Lee, a research fellow at the British Antarctic Survey and the lead author on the paper.

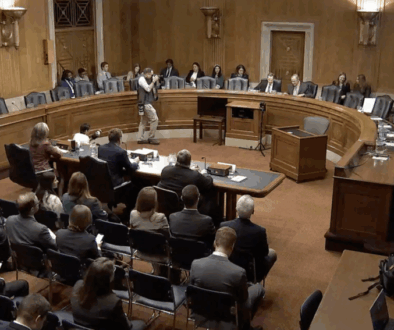

The study is the result of a workshop, held in 2017, that brought 29 scientists including Lee together to discuss and analyze Antarctic conservation strategies. The findings were published days after the close of COP15, when nearly 200 nations agreed to a set of goals for conserving biodiversity after two weeks of negotiations in Montreal.

The authors of the study recommended a combination of cost-effective strategies that would ultimately help protect Antarctic species from the many threats facing the continent, including pollution, climate change, invasive species, and infrastructure built by humans.

The top cost-effective strategies identified by the researchers included minimizing the impacts of human activity, preventing, reducing, and minimizing the impacts of new infrastructure, and reducing levels of transport to the continent. Since much of the human activity in Antarctica is a result of scientific research, implementing these strategies could mean that scientists would need to figure out ways to conduct research remotely, by using drones or other technology to reduce disturbances to wildlife.

Researchers estimated the recommended strategies would cost $23 million; a cost Lee described as “remarkably cheap” compared to other conservation efforts across the globe. “These might be easy conservation wins,” she said.

Climate change, said Lee, is the biggest threat to Antarctic biodiversity. Finding ways to transition the global energy system and mitigate climate change, she said, should be a top priority for Antarctic conservation.

The biggest barrier to improving the state of Antarctic conservation, said Lee, is money — both finding funding and determining how to disburse it. However, the study lays out detailed plans for many of the proposed strategies, meaning that once such methods receive funding, some of them will be “quite easy” to implement, she said.