Postcard from California: Food waste law fights hunger and climate change

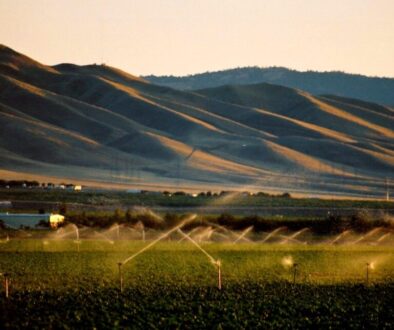

California produces far more food than any other US state, but we throw a lot of it away. Meanwhile, more than one in five Californians don’t always know where their next meal is coming from. Food insecurity is higher among Black and Latino households, and inflation is making the problem worse.

California produces far more food than any other US state, but we throw a lot of it away. Meanwhile, more than one in five Californians don’t always know where their next meal is coming from. Food insecurity is higher among Black and Latino households, and inflation is making the problem worse.

Now the state is aiming to relieve hunger by reducing food waste – and at the same time, help to address climate change.

A state law that took effect this year requires businesses and facilities that sell or serve food to donate leftover edible items they would otherwise throw out to local food banks. Grocery stores, wholesalers and distributors had to start donating earlier this year. Restaurants, hotels, schools, hospitals, state office cafeterias and event venues must comply by January 2024.

According to the state agency CalRecycle, Californians send more than 11 billion pounds of food to landfills every year. Nationally, about 80 billion pounds of wasted food goes to the dump yearly, making food the single largest constituent of municipal landfills.

Food rescue

While not all discarded food is fit to eat, the newly implemented law – SB 1383 – requires that by 2025 California will recover 20% of wasted food to feed people in need. Washington State has the same goal, but by mandating fines for non-compliance, California’s is the strongest “food rescue” measure in the country.

Rescuing edible food is only one front in the war on food waste.

The law also requires all Californians to separate food scraps, yard clippings and other organic waste from trash and recycling. Organic waste must go into a green bin for curbside collection and then is hauled to a closed-air composting facility or a biofuels plant, not an open-air landfill.

San Francisco and some other California cities have separated and composted food scraps and green waste for years. Others, including Los Angeles, phased in the program this year. Some cities (including Modesto, where I live) got waivers to delay organics collection until 2023.

CalRecycle says it’s “the biggest upgrade to our waste and recycling system since California started curbside recycling in the 1980s.”

But how does it help in the climate crisis?

Methane and climate

When food and other organic waste decomposes in a landfill, it emits methane, a powerful greenhouse gas. Historically, efforts to cut greenhouse gases have centered on carbon dioxide. But in the short term, methane has more than 80 times the atmospheric warming potential of CO2.

“When green waste and food scraps are dumped into landfills, they produce high levels of methane emissions for up to 18 years, making them one of the top sources of methane,” CalRecycle spokesman Lance Klug said in an email. “SB 1383’s green waste recycling and food rescue targets will cut climate pollution equal to taking three million cars off the road.”

CO2 lingers in the atmosphere for hundreds to thousands of years, but methane dissipates in about a decade. That makes it low-hanging fruit in the race to reduce greenhouse gases fast enough to avoid the worst impacts of climate change. While efforts to control CO2 are no less urgent, sharp reductions in methane will have an impact more quickly.

That’s why the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says holding global warming below the level that would trigger irreversible tipping points could hinge on how much the world can reduce methane emissions by 2030. In November, methane received heightened attention at COP27, the conference of nations that are parties to the Paris climate accords.

The largest sources of methane emissions are from agriculture, particularly livestock manure, and the energy sector, particularly oil and gas drilling and production. About one-fifth comes from waste, including organics and plastics, which emit methane when exposed to sunlight in landfills or in the oceans.

At COP27, the US Environmental Protection Agency announced sweeping new regulations cracking down on methane leaking from oil and gas wells. Drill sites also release toxic air and water pollutants that endanger the health of people who live nearby. Although in 2016 the EPA and the US Department of Agriculture launched a voluntary private-sector initiative to reduce food waste, the agencies have put scant resources behind it.

Zero-waste cities

That has largely left the task of keeping methane-emitting waste out of landfills to local governments.

Cities nationwide, including New York, Seattle and San Diego, have adopted zero waste goals that include diverting organic waste from landfills. In 1996, San Francisco was the first city in the country to begin curbside food waste collection. Today the city diverts 80% of organic and other waste from landfills, the highest rate of any city in North America.

A key zero waste strategy is the age-old practice of composting, which is no longer just the habit of backyard gardeners, but a centralized program that turns organic waste into a nutrient-rich soil supplement.

San Francisco’s food waste is trucked 80 miles to a facility that produces hundreds of tons of compost a day for sale to orchards, vineyards and farmers. It provides revenue for the employee-owned disposal company, and is a double win for the climate: Compost-enriched soil is more efficient at sequestering CO2 emissions from agriculture operations.

For Californians in cities new to organic waste separation and collection, complying with SB 1383 will be an adjustment – and not just in our recycling habits.

Some small towns and rural areas are finding it costly to rescue food and compost food waste, even with state grants. My monthly waste collection bill will go up by more than $5 next year, and by a similar amount in 2024. Some of my neighbors are grumbling about one more increased expense in a time of high inflation.

I get it. But to help feed hungry Californians, keep millions of tons of methane from heating the planet, and reduce emissions of other hazardous air pollutants from landfills, the costs are more than worth it.

- Bill Walker has more than 40 years of experience as a journalist and environmental advocate. He lives in California’s San Joaquin Valley.

(Opinion columns published in The New Lede represent the views of the individual(s) authoring the columns and not necessarily the perspectives of TNL editors.)