Postcard from California: Big Oil’s campaign to kill drilling ban near homes and schools

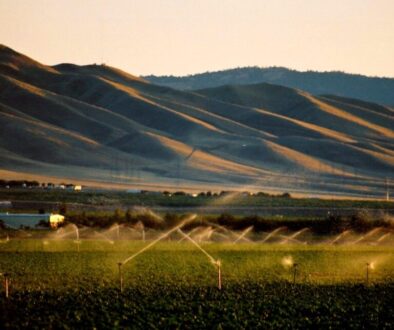

In September, California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a landmark bill banning new oil and gas wells within 3,200 feet – about two-thirds of a mile – of homes, schools, day care centers, healthcare facilities, parks, and businesses open to the public. The measure also banned “reworking” old, unproductive wells lying within the buffer zones.

It was a huge win for environmental justice advocates, capping a decade-long campaign to protect Californians from the well-documented health risks of living near drill rigs, including premature births, heart disease and asthma. More than 7 million Californians – disproportionately lower-income people of color – live within a mile of active oil or gas wells.

Newsom signed the bill, SB 1137, on a Friday. The ink had hardly dried when, the following Monday, the oil and gas industry launched a petition drive to throw out the new law.

Under California’s referendum and initiative process, if enough registered and verified voters sign a petition to overturn a law, it goes on the ballot in the next general election. But even before voters get a chance to decide, the law is suspended until the election. Once hailed as a progressive tool of grassroots democracy, the initiative process is increasingly used by special interests to kill laws they don’t like.

Two weeks before Christmas, the California Independent Petroleum Association (CIPA) announced it had gathered almost a million signatures on a petition to block the law, which was supposed to take effect this month. If roughly two-thirds are certified by county and state election officials, the buffer zones provided for by SB 1137 can’t take effect until after November 2024.

It’s a despicable move by fossil fuel interests. The industry has already spent or raised more than $20 million to try to kill the historic measure aimed at protecting public health. Even if they are only successful in delaying the law’s implementation, the move gives the industry almost two years to drill new wells that can keep pumping after the restrictions kick in.

Deep pockets

So how did they do it? Deep-pocketed corporate-backed initiative campaigns can hire armies of professional signature gatherers who wield clipboards outside supermarkets and malls, earning payment for each voter they sign up.

Investigations in November by Inside Climate News, and in December by The Associated Press (AP), found that some canvassers hired by consultants running CIPA’s Stop the Energy Shutdown campaign lied or misled voters asked to sign the petition.

Several voters said canvassers told them the petition they were being asked to sign would ban new drilling near homes and schools – exactly the opposite of what it would do. Others said the petition was explained as an effort to prevent higher gas prices – which in fact are tied not to in-state production but to the global oil market. When challenged, canvassers said they were just repeating what they’d been told.

It’s illegal to intentionally make false statements when circulating a petition, but that’s hard to prove. (CIPA denies the canvassers were told to mislead voters.) The California Secretary of State’s office confirmed to the AP that it had gotten complaints from across the state about the petition tactics but would not confirm an ongoing or pending investigation.

Stop the Energy Shutdown is not the California oil industry’s first campaign to overturn common-sense drilling regulations.

In 2020, Ventura County supervisors enacted rules upgrading environmental review of oil and gas developments. A political action committee linked to Aera Energy, a company jointly owned by affiliates of Shell and ExxonMobil, mounted a successful petition drive that suspended the rules until voters could decide.

Oil interests spent more than $6 million to campaign against the new rules, which were narrowly defeated this summer. If the industry spent that heavily in a county with a relatively small oil economy, imagine the resources it could deploy in a statewide campaign with much more at stake.

Industry “disinformation”

The California oil and gas industry, long accustomed to getting its way, now feels it’s fighting for its life. Last month a Western States Petroleum Association spokesperson whined to Politico that Newsom “wants us out of business.”

The governor has ordered a ban on sales of new gasoline cars starting in 2035 and called for phasing out all oil and gas drilling by 2045. In December, he unveiled a proposed price-gouging penalty on oil companies’ excess profits, which he charged are one reason Californians pay the highest gasoline prices in the US. In 2022, his administration denied all permits for new fracking wells in Kern County, center of the state’s petrochemical industry.

The industry’s campaign against restrictions on new wells near homes and schools may well backfire. Shortly after CIPA announced it had apparently gathered enough signatures on the petition, the state’s main oil regulatory agency called for an emergency order to impose the terms of SB 1137 this month.

If the industry’s initiative is certified, which could take until April, the emergency order would be moot. But Newsom would still have the power to establish buffer zones independently.

The Newsom administration began drafting buffer zone regulations last year, before deferring the issue to legislators. In an editorial, the Los Angeles Times implored the administration to resume the process and in the meantime deny all applications for new drilling in the buffer zones.

“It’s not good enough,” the Times wrote, “to just hope that Californians will do the right thing and see through a referendum that, if the signature-gathering process is any indication, will be clouded in fossil fuel industry disinformation designed to confuse voters.”

To protect public health, end the unacceptable practice of oil and gas drilling near the places Californians live, work and play, and stand up to Big Oil’s attempt to pervert direct democracy, the governor must act.

- Bill Walker has more than 40 years of experience as a journalist and environmental advocate. He lives in California’s San Joaquin Valley.

(Opinion columns published in The New Lede represent the views of the individual(s) authoring the columns and not necessarily the perspectives of TNL editors.)