Postcard from California: A phantom lake rises again

At the start of the California Gold Rush in 1849, Tulare Lake was the largest body of fresh water west of the Mississippi River: In wet years, the shallow inland sea that is fed by four rivers covered 800 square miles or more of the lower San Joaquin Valley.

After white settlers displaced the indigenous Yokuts Indians, ferries and steamships plied Tulare Lake’s ports, and a thriving commercial fishery supplied salmon, sturgeon, and terrapins to the finest restaurants in San Francisco.

Fifty years later, Tulare Lake was dead.

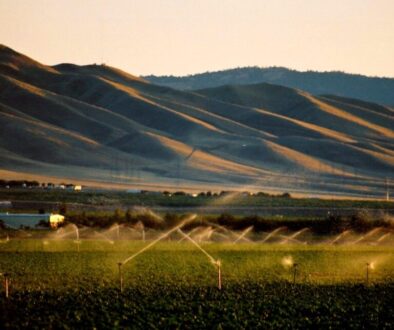

By the turn of the century, farmers had tapped its tributaries for irrigation, cutting the rivers’ flow. In the 1920s, Georgia cotton king J.G. Boswell came west and drained the remaining wetlands to stake out what became the world’s biggest cotton plantation. After the Depression, huge taxpayer-subsidized irrigation projects transformed the valley, including the desiccated lakebed, into one of the most productive agricultural regions in the world.

In rainy years, low-lying parts of the Tulare Basin flooded, and old-timers recalled the prediction of a Yokuts elder named Yoimut. Before her death in 1936, Yoimut predicted to an ethnographer that Tulare Lake would return one day. “It will fill up full and everybody living down there will have to go away,“ she said.

This year, her words are again ringing true.

Since January, a wave of atmospheric rivers dumped torrents of rain and snow on California, dramatically ending the extreme drought that began in 2020. More than 10,000 acres in the Tulare Basin flooded, drowning fields and orchards and forcing thousands of residents to evacuate towns in and around the dry lakebed.

The worst is yet to come.

Snowpack in the mountains above the basin is three times its recorded average. As it melts, more water than is held in Lake Mead, the nation’s largest reservoir, will cascade toward the valley floor. Experts say Tulare Lake could swell beyond Gold Rush limits, potentially wiping out entire towns, and the basin will remain flooded for years. In surrounding Kings County, damages and lost revenue could reach $2 billion.

“This year’s severe storms and flooding is the latest example that California’s climate is becoming more extreme,” Karla Nemeth, director of the state Department of Water Resources (DWR), said in a news release.

“After the driest three years on record and devastating drought impacts to communities across the state, DWR has rapidly shifted to flood response and forecasting for the upcoming snowmelt,” Nemeth said. “We have provided flood assistance to many communities who just a few months ago were facing severe drought impacts.”

It’s tempting to feel a guilty schadenfreude about the lake’s resurrection – a grim reminder that nature bats last.

Draining the lake was an act of incredible hubris that brought great wealth to Boswell and to his heirs, who still grow cotton, tomatoes and alfalfa on 150,000 acres in the basin. Industrial agriculture has contaminated drinking water with pesticides, devastated fish and wildlife habitat, and exploited generations of farmworkers, who overwhelmingly are undocumented Latino immigrants.

A more appropriate response is compassion, because the disaster is hitting those same workers hardest. Growers are eligible for federal relief funds, but many farmworkers have lost their homes and livelihoods.

“When crops get lost because of these floods, farmers get a lot of that made up; there’s disaster relief“ through the US Department of Agriculture, a United Farm Workers spokesman told a Fresno TV station. “There’s no such program for farm workers who lose wages.”

Drying out the Tulare Basin will take years and cost billions of dollars. But as climate change increases the likelihood of superstorms slamming California more frequently, this won’t be the last time the lake re-emerges.

The smart thing is to restore the lake for good.

For decades, the California ag industry has lobbied for new dams and reservoirs to store irrigation water.

In 2014, Congress authorized development of plans for the Temperance Flat Dam, which would flood the San Joaquin River Gorge, about 100 miles upstream from Tulare Lake. The state issued bonds for the project, but in 2020 it was put on hold, in part because of fierce opposition from environmental groups. Steve Haze, executive director of the nonprofit Tulare Basin Watershed Partnership, says restoring Tulare Lake to even a fraction of its historic size would provide twice as much water as the proposed Temperance Flat Dam project.

In an interview, he cited state studies that estimate the cost of restoration and new irrigation infrastructure would be about 10% of Temperance Flat’s $3 billion-plus price tag. Restoring the lake would also create a sustainable recreation economy for disadvantaged San Joaquin Valley communities, improve drinking water quality and revive fish and wildlife habitat.

“We have in front of us the greatest opportunity to shape the future of the Tulare Basin since Boswell drained the lake,” Haze said. “Will we continue to manage it for the benefit of a handful of landowners? It took us decades to get in this mess, and it will take decades to get out. But we can’t just close our eyes and pretend it won’t happen again.”

Bill Walker has more than 40 years of experience as a journalist and environmental advocate. He lives in California’s San Joaquin Valley.

(Opinion columns published in The New Lede represent the views of the individual(s) authoring the columns and not necessarily the perspectives of TNL editors.)

(Featured photo of Lake Tulare area by US Geological Survey.)