Vast majority of global methane emissions go unregulated, says new study

Governments around the world are failing to effectively regulate and mitigate harmful emissions of methane, a greenhouse gas with a climate warming potential more than 25 times stronger than carbon dioxide, according to research published Friday.

Only 13% of global emissions from methane are covered by existing public mitigation policies, the researchers reported in the journal One Earth.

“Significant and underexplored [methane] mitigation opportunities exist,” the authors wrote.

The research comes on the heels of a report issued Thursday from the Environmental Integrity Project (EIP) showing that methane emissions from just 1,100 US landfills have a climate-warming effect equivalent to the yearly emissions of 66 million gas-powered vehicles.

Methane makes up about 12% of US greenhouse gas emissions stemming from human activities, including agricultural operations, fossil fuel extraction and use, waste management practices, and decay of organic waste in municipal solid waste landfills. Agriculture is the largest single US source of methane emissions, according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Global methane emissions are currently rising faster than at any point since the 1980s. To try to keep global warming from exceeding the warming limit of 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit set by the Paris Agreement, global methane emissions must be reduced by at least 40-45% of 2020 levels by 2030, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Gaps in emissions policies

Tackling methane emissions is a “critical” strategy if the rate of global warming is to be slowed, the authors state in the new paper. With less than 15% of methane emissions under regulation, global climate change policy has enormous room for improvement when it comes to methane, they say.

The authors reviewed 281 policies across high methane-producing sectors, including energy, waste, and agriculture. They determined that current methane policies, which vary sharply on a regional basis, are too lax and are largely based on data that uses estimates of methane emissions rather than actual measurements.

Roughly 90% of national methane emissions policies they identified were in North America, Europe, and Asia, while Central and South America, Africa, the Middle East, and Russia had far fewer methane policies. The regions with the fewest methane policies account for about 80% of global methane emissions.

About half of the policies the researchers found targeted emission from fossil fuels, while most other policies targeted agricultural and waste sectors.

In agriculture, most methane emissions come from animal manure and enteric fermentation (a methane-emitting part of the livestock digestion process). In the US, livestock make up about 27% of all methane emissions. The new research found that most policies regulated emissions from animal manure, or incentivized the controversial production of biogas from manure, rather than emissions from enteric fermentation, though enteric fermentation makes up the majority of methane emissions from livestock.

Methane is emitted across many parts of the energy sector, including the extraction, production, transport, and use of fossil fuels. Natural gas, which is used widely as a fuel source, is predominantly made up of methane. Existing policies to regulate methane in this sector mostly focused on emissions from intentional releases of methane by the gas and oil industry during production.

While many policies aimed at reducing greenhouse gases focus on transitioning to renewable energy, such transitions won’t automatically eliminate methane emissions, since abandoned coal mines and oil and gas wells can continue to emit methane.

One reason for the lack of methane policies worldwide is a history of opposition from the fossil fuel industry and agriculture industry, said Marie Olczak, the lead author of the paper and a PhD candidate at Queen Mary University of London. Existing policies targeting fossil fuels were found to be less stringent than those targeting agriculture and landfill emissions.

The authors argue that significant opportunities to improve methane policy globally lie both in the creation of new regulations and through increasing the strength of existing policies, especially policies covering the fossil fuel sector.“We already know what we could do to improve the situation,” said Olczak. “We really need policies to drive changes in how industry operates. Without these policies, we cannot expect the practices of these companies to change.”

Controlling methane from landfills

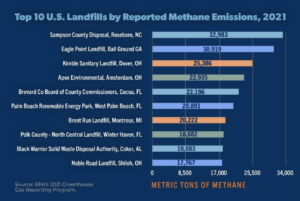

According to the EPA, municipal landfills make up about 14% of total methane emissions in the US. The new report from EIP shows that the top 10 methane-emitting landfills, all located in the Southeast and Midwest, emitted enough methane in 2021 to cause warming equivalent to the yearly emissions from five coal-fired power plants.

“EPA is failing to adequately control methane from landfills, a huge source of greenhouse gases, and we can no longer ignore this problem with the climate crisis heating up,” said Leah Kelly, Senior Attorney at the Environmental Integrity Project and one of the report’s authors, in a statement.

In the report, EIP calls for the EPA to require more landfills to have methane collection systems, to ask landfills to better monitor their methane emissions, and to strengthen requirements for landfills to report their methane emissions. The report also calls for increased efforts to raise awareness about how food waste impacts methane emissions.

In 2022, EIP and other groups sued EPA, arguing that the agency’s methods for estimating emissions of air pollutants from landfills are outdated and underreport actual emissions. In 2023, EPA and EIP reached an agreement that requires EPA to review the current defects in methodology used to report landfill methane and if necessary, revise them.

(Featured image: A gas flare in Romania. Photo by the Clean Air Task Force.)

EWG

EWG