Postcard from California: In climate crisis, farmworkers need more protection from heat

It’s been over 20 years since a 24-year-old migrant farmworker named Constantino Cruz collapsed and died following a nine-hour shift picking tomatoes in 107-degree Fahrenheit heat near Bakersfield, California.

Cruz spent four days in the hospital before dying on July 31, 2005. He was the fourth California farmworker to die of heat related illness that month.

Cruz’s death helped spur then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger to issue emergency regulations requiring that on hot days agricultural employers must make sure farmworkers get plenty of water, ready access to shade and rest breaks. The emergency measures were later codified into the first US state law mandating heat protections for farmworkers and other outdoor workers.

Arturo Rodriquez, who at that time was president of the United Farm Workers (UFW), told the Los Angeles Times: “It is tragic that so many farmworkers had to die before action was taken.”

But since California’s landmark action, only three states – Colorado, Oregon and Washington – have passed similar heat safety regulations for farmworkers, and there are no federal safety rules for farmworkers or others who must toil under the sun, meaning most US farmworkers lack legal protection from heat.

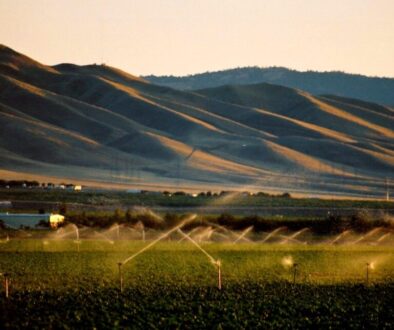

The problem is not going away. Average temperatures in the San Joaquin Valley in California are projected to rise by as much as 5 degrees by 2050. And in crop-growing counties across the nation, the number of days considered unsafe because of heat is forecast to nearly double by 2050, according to a University of Washington study.

Stalled efforts

There are ongoing efforts to address the issue. Two years ago, the Biden administration directed the Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA) to develop heat safety standards for all outdoor workers. But former OSHA chief David Michaels recently wrote that because Congress has starved the agency of “anywhere near the resources it needs to fulfill its mission,” the slow-moving rulemaking process is unlikely to produce a national heat standard any time soon.

And last year US Rep. Judy Chu of California introduced the Asunción Valdivia Heat Illness and Fatality Prevention Act to require OSHA to set a national heat safety standard within a year of enactment. The title of the measure honors a 53-year-old migrant worker who died of heatstroke in July 2004 after a 10-hour shift picking grapes in 100-degree-plus heat.

But while Chu’s bill passed the House labor committee, it stalled after Republicans took back the majority last year.

California’s heat safety regulations apply when the temperature is at least 80 degrees. Employers must provide workers at least one quart of cool water every hour, and nearby shade where workers who feel symptoms of heatstroke may take a break of at least five minutes.

If the heat reaches 95 degrees, workers must get a rest period of at least 10 minutes every two hours, with additional breaks if the shift goes beyond eight hours. Last year, a proposal to add extra protections at “ultrahigh” temperatures –– 105 degrees or higher – died in the state Legislature.

The onus is on employers. They must make sure workers and supervisors are trained to know the rules, the signs of heat illness, and how to get medical help in an emergency. They may not push workers taking a break to return to work too soon, or dock workers’ pay for taking a break.

Violations are misdemeanors, with fines according to the seriousness of the violation.

There have been signs of improvement. In 2021, researchers from the University of California at Los Angeles and Stanford University found that heat-related injuries for all outdoor workers in the state fell by about 30% since the law took effect.

The study did not break out farmworker injuries, however, and a 2015 investigation by the Desert Sun of Palm Springs suggests Cal/OSHA, the state’s counterpart to the federal workplace safety agency, may be undercounting heat related injuries and deaths of farmworkers. The newspaper reported: “Most every year, farmworkers die in 90 or 100 degree heat but are never counted as heat related fatalities.”

The investigation found that while Cal/OSHA counted 55 farmworker deaths from 2008 to 2014, it categorized only six as heat related. In 2014, 13 farmworkers died after working in the fields, but Cal/OSHA said none were linked to heat, including a man who died after picking lemons in 109-degree heat in Riverside County.

Flouting the rules

In 2009 and 2012, the UFW filed lawsuits accusing Cal/OSHA of systematically failing to enforce the heat rules and claiming the death toll was much higher. The suits were settled in 2015, with the agency promising to step up enforcement.

Still, many employers continue to flout the rules.

Last year, the Community and Labor Center of the University of California at Merced surveyed more than 1,200 farmworkers throughout the state. More than 40% said their employer never provided a plan for preventing or responding to heat illness. Nearly one in six did not receive the minimum number of rest breaks required by law. And more than a third said they would not be willing to report their employer for non-compliance, most because of fear of retaliation or losing their jobs.

It is indisputable that farmworkers’ already severe heat risks will get worse.

California must redouble efforts to protect farmworkers from heat. Congress and OSHA must quickly implement national heat safety standards. In the meantime, as California did in 2005, the Biden administration should announce emergency measures to protect those who brave the heat to put food on our tables.

- Bill Walker has more than 40 years of experience as a journalist and environmental advocate. He lives in California’s San Joaquin Valley.

(Opinion columns published in The New Lede represent the views of the individual(s) authoring the columns and not necessarily the perspectives of TNL editors.)

(Featured image from Farmworker Justice.)