GE, Bayer, blamed for child’s cancer in a community awash in PCB pollution

A Massachusetts mother filed a lawsuit on Tuesday blaming widespread PCB pollution by General Electric (GE), Monsanto and its German owner Bayer AG, and several other companies for causing her 9-year-old son to develop leukemia and suffer repeated debilitating medical treatment.

Crystal Czerno alleges, among other things, that GE knowingly contaminated her son Carter’s elementary school and playground with PCB waste while downplaying the harm it could cause. The school is located in the town of Pittsfield, just north of a GE facility that made electrical transformers containing PCBS for more than 40 years. PCB-laden soil from the GE site was spread over the school grounds.

The lawsuit accuses the companies of using the community as a “dumping ground” for “toxic and cancerous” chemicals.

“As a mom I am supposed to protect my babies and I must now live with the fact that I moved them into a home and a school that put them in direct danger,” Czerno said. “My son Carter has paid the price.”

The young boy has undergone multiple rounds of chemotherapy, as well as full-body radiation, and multiple stem cell transplants and bone marrow biopsies, according to the lawsuit. Another bone marrow biopsy is scheduled next week, his mother said.

Czerno’s lawyer, Thomas Bosworth, said he has several more claims that will be filed in the coming days from area residents struggling with health problems they believe are linked to PCB pollution.

“This is not just about getting justice for these victims,” said Bosworth. “It is also about the future of the community.”

“A significant hazard”

The Massachusetts case is the latest in a string of lawsuits filed around the country that aim to hold the makers and users of PCBs accountable for decades of persistent environmental contamination. The chemicals, formally called polychlorinated biphenyls, have long been linked to an array of human health concerns, including leukemia and other cancers. In one study of nearly 400 children, researchers found that detection of PCBs in the home was associated with a 2-fold increase in risk for acute lymphocytic leukemia.

PCBs are also known to be harmful to fish and wildlife. They do not easily break down, making eradication difficult.

Monsanto, purchased by Bayer in 2018, manufactured PCBs from the 1930s to the late 1970s for use in coolants and lubricators in electrical equipment. Internal corporate records revealed through litigation show the company continued to sell PCBs for years while knowing they posed health risks and publicly downplaying the risks. The new lawsuit draws on those documents, citing several from the 1950s and 60s that speak of internal corporate concerns about PCB toxicity, potential legal liability, and the “universal presence as residues in the environment.”

The United States banned PCBs in 1979 but PCB pollution remains pervasive. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has called them “a significant hazard to human health and the environment.”

Several thousand municipalities have sued over PCB contamination of waterways, and Attorneys Generals of several states have also sued over contamination of schools and other properties. Bayer so far has agreed to pay $650 million to municipal entities for the PCB water pollution.

In addition, Bayer is facing claims from several people who worked at a school in Monroe, Washington. Three teachers won $185 million two years ago in a lawsuit against Monsanto, alleging they suffered brain damage from PCBs in fluorescent lights at the school where they worked. Others associated with the same school have also won verdicts recently.

Bayer claims it has “strong defenses” against such cases, including the fact that it did not make the lighting products that contain the PCBs, and says the schools actually could be responsible because they’ve known for years of the need to address PCB-containing products in their schools.

In a statement, Bayer said it has “great sympathy” for the plaintiff in the lawsuit but denied any responsibility. Monsanto did not manufacture or dispose of PCBs in the greater Pittsfield area and had no responsibility for, or control over, the GE plant, the company said. The company additionally disputed a connection between exposure to PCBs and leukemia.

GE did not respond to a request for comment.

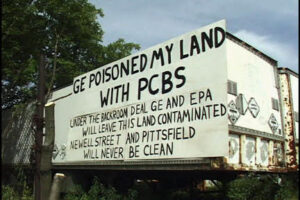

Protesting a “massive” PCB dump

Czerno’s lawsuit comes against the backdrop of an ongoing battle over a federal mitigation plan for PCB pollution in the Housatonic River in Berkshire County, Massachusetts, where Czerno and her family live.

The EPA has laid out a cleanup plan with GE to relocate up to 1 million cubic yards of PCB-contaminated sediment from the river. Much of the contaminated waste will go into a landfill in the county, though the EPA maintains the most toxic material would be shipped out of state.

But environmentalists, residents and community leaders have protested the plan, claiming dredging the river and then trucking the waste to a nearby site within the county will do little to protect community residents and could put them at added risk, in part because the designated landfill is near the town’s water reservoir. They want the waste removed from the community entirely.

Research shows that people can be exposed to PCBs not only through water, but also by breathing in contaminated air or exposure to contaminated soil, and ingesting contaminated food.

The opponents to the EPA plan have sued the EPA to block what they call the “massive PCB dump” in Berkshire County. But so far they are losing the fight. Last month a federal appeals court rejected their challenge to the EPA.

A “life-altering” toll

While her neighbors fight the PCB landfill plan, Czerno said her focus is on protecting her family. They no longer eat the vegetables from the backyard garden, and Czerno said she wonders where she can send her son to school if and when he is well enough to attend.

Caring for Carter in and out of hospitals has forced her to quit work, and taken a “life-altering” toll on her other son as well as her extended family.

Doctors have told her that even if Carter is eventually declared cancer-free, his life expectancy is significantly shortened due to all the treatments he has undergone.

“Every day I look at Carter and I wonder if the cancer is going to take him away from me,” she said. “Sometimes when we are lying in bed at night I record our conversations and dread the day they are all I have left.”

(This story is co-published with The Guardian.)

EWG

EWG