Justices ring death knell for isolated US wetlands

By Judy Helgen

A recent decision by the US Supreme Court strips away protections from our nation’s remaining treasure of isolated wetlands. The court has reverted to the dark days when wetlands were viewed as dirty swamps to be drained — habitats with no value.

There’s a convoluted legislative and regulatory history which gave the US Army Corps authority to oversee the nation’s navigable waters. The Corps protects waters that have a significant nexus, or connection, to a navigable water like a river. On that basis, the court removed isolated wetlands as Waters of the United States. Yet scientists have documented that most waters — including isolated wetlands — are connected, even when they don’t have an obvious nexus.

As a result, the justices have rung a death knell for these unique, watery environments.

Permanent and semi-permanent wetlands support an amazing diversity of underwater life: mayflies, dragonflies, small algae-eating crustaceans, and other quietly beneficial species. Isolated wetlands also provide physical services, such as holding water on the landscape and settling silt and pollutants.

Biologists like me who care about our watery environments are in shock.

Nationwide, less than half the country’s original 220 million acres of wetlands remain after vast areas were drained, primarily to create farmland. Farmers had no malicious intent; their crops are a major contributor to the Midwest economy. Minnesota has already lost half of its 20 million acres of wetlands because of drainage to create farmland.

Shouldn’t we protect those that remain?

The National Association of Realtors exulted that property owners are free to use their land to the fullest extent possible. Does this mean that private landowners have the right to pollute or otherwise alter their land? Anything goes?

I remember when initiating a citizen wetland biomonitoring program back in the late 1990s, a landowner rights organizer castigated us for training ”wetland vigilantes” who might help the government take over their land. I envisioned our volunteers wearing Wetland Vigilante T-shirts as they waded into a pond with dip nets to sample the aquatic invertebrates.

Minnesota’s 1992 Wetlands Conservation Act provides some protections for isolated wetlands. But WCA lists dozens of exemptions that can remove or qualify protections for wetlands, particularly smaller ponds. I fear that unique, shallow vernal pools have no one looking out for them and their tadpoles, fairy shrimp and other diverse creatures.

Also, only part of WCA’s goal of achieving a “no net loss” of the “quantity, quality and biological diversity” of wetlands is being accomplished. In reality, quantity gets more oversight than water quality and biodiversity.

Here’s why: If a wetland will be harmed, a replacement plan must be approved by the state, requiring restoring a wetland or purchasing credits from a commercial wetland bank. Neither the replaced wetlands nor those in wetland banks are monitored for their biological diversity, nor long-term water retention. Scientists have documented that restored wetlands do not replace natural wetland biodiversity.

I wish I could take Supreme Court justices outside on an evening in spring to stand by a wetland and listen to the mesmerizing calls of male frogs, like the high-pitched chirps of tiny spring peepers, or the two-tone trills of tree frogs. Show them females laying eggs in the shallow water, eggs that will develop into tadpoles and then transform into small adults that hop onto the land to feed on bugs.

I wish I could have them sample the invertebrates in a semi-permanent pond and have the epiphany — as one of our volunteer monitors experienced when he first saw a dragonfly larva. He had no idea it would transform into a beautiful adult dragonfly.

Better yet, watch a nymph crawl up a cattail stem, split open, and release a compacted adult which slowly unfolds and spreads wide its wings, then zooms around, consuming mosquitoes and other bugs. Or peer into a shallow, temporary pond and watch golden-colored crustacean fairy shrimp swimming on their backs, creatures whose fossils date back 500 million years.

I wish I could take them to a small pond at the Kelley Land and Cattle Co., whose 2,600 acres of land (thanks to efforts by the MN Land Trust) will soon will be sold to DNR and Washington County and be protected from development.

Years ago, I had permission from the family to sample the Kelley wetlands. One spring, I trekked downslope through a wooded area, guided by the calls of frogs to a pond recently refilled by snow melt and spring rains. Dormant resting eggs of invertebrates were hatching and bringing new underwater life. Frogs were mating. From a colleague at the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency I learned the pond could be 3,000 years old.

Returning later in spring, the wooded pool was packed with tadpoles and the water alive with fierce predatory aquatic beetles, fairy shrimp and tiny clam shrimp. Frogs still called in the woods.

By late summer, the small Kelley pond started to go dry again. I stepped carefully onto the moist soil. I stood still. Newly matured wood frogs, tree frogs and leopard frogs squatted on the damp mud and basked in the sun. Tiny green frogs, almost invisible, perched on plants. Gray tree frogs blended into the bark of nearby trees, clinging with their sucker toes. By now the pond’s aquatic invertebrate life had disappeared along with the water. But I knew otherwise: Within the mud, the seeds of life would carry on until the following spring when, once again, diverse life would emerge anew, develop, flourish and reproduce a new generation.

If our Supreme Court justices were there with me, might they see wetlands as important Waters of the United States? Waters to be cherished and protected?

- Judy Helgen, PhD, is a retired scientist from the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency where she worked to develop biological monitoring protocols for wetlands. She is the author of Peril in the Ponds: Deformed Frogs, Politics, and a Biologist’s Quest, 2012. U Mass Press.

This article first appeared in the Minnesota Reformer.

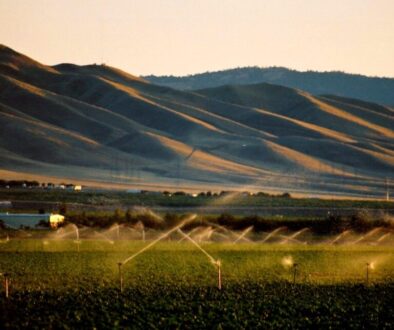

(Photo provided by Judy Helgen.)

(Opinion columns published in The New Lede represent the views of the individual(s) authoring the columns and not necessarily the perspectives of TNL editors.)

September 1, 2023 @ 2:20 am

“If our Supreme Court justices were there with me, might they see wetlands as important Waters of the United States? Waters to be cherished and protected?”

I wish they would, but I fear corporate and ideological money will rule the day for a while to come.