Postcard from California: Freeways fracture communities, poison the air and heat the planet

In 1957, California opened its first double-decker freeway: The Cypress Street Viaduct, slicing through the heart of West Oakland toward the Bay Bridge to San Francisco. The construction displaced hundreds of Black families and businesses from a neighborhood once known as the Harlem of the West. The freeway’s eight lanes cut off West Oakland from downtown, stifling development and exposing residents to the toxic pollution of 160,000 vehicles a day.

On Oct. 17, 1989, the Loma Prieta earthquake rocked Northern California, collapsing a mile of the freeway’s upper span onto the lower deck. Though first responders feared that hundreds of rush-hour commuters had been crushed, miraculously the death toll was limited to 42. West Oakland residents organized and pushed Caltrans, the state transportation agency, to reroute a new approach to the bridge away from the neighborhood. The Cypress Street Viaduct was replaced by Mandela Parkway, a tree-lined boulevard with walking paths and bike lanes. Dozens of new businesses sprang up and air pollution dropped dramatically.

It shouldn’t take a natural disaster to open our eyes to the damage freeways do to disadvantaged communities.

West Oakland was just one of many lower-income communities of color across the country where residents, lacking the resources and political clout to resist “urban renewal,” were displaced by freeways. A 2021 Los Angeles Times investigation found that during construction of the US Interstate Highway System from the 1950s to the early 1990s, “more than 1 million people were forced from their homes, with many Black neighborhoods bulldozed and replaced with ribbons of asphalt and concrete.”

Thankfully, some places are trying to fix the mistakes of the freeway-building era. In February, the Biden Administration launched a nationwide initiative to restore communities ripped apart by freeways. The first grants will give $36 million to California, including funds for Caltrans to study removal of I-980, another freeway blocking West Oakland from the booming Uptown district, and for other projects in Long Beach, Pasadena, San Jose, and Fresno. In March, state legislators formed a new select committee to explore strategies for reconnecting freeway-fractured communities.

The first freeways were built in Southern California before World War II and are as indelibly associated with the state as beaches and redwoods. If national parks are America’s best idea, freeways may be California’s worst. They can be forbidding barriers to a city’s special natural setting. After San Francisco’s Embarcadero Freeway was torn down due to damage from a 1989 earthquake, a once-decaying waterfront came alive again with joggers, cyclists, streetcars, and cafés.

Freeways are also deadly sources of airborne pollutants. The I-710 Freeway corridor, the daily route of 40,000 cargo trucks from the Port of Los Angeles, is known as “the diesel death zone” for the high rates of lung cancer, heart attacks and strokes suffered by people living near it.

And freeways don’t ease traffic – they cause more traffic. It’s a fundamental law of road congestion: A new or widened freeway inevitably attracts more drivers, and soon traffic is just as bad or worse than before. A study by the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School found that a few years after the $1 billion-plus widening of I-405 in Los Angeles, an average mid-afternoon trip took 50% longer. More vehicles driving more miles for more minutes – what Caltrans calls vehicle miles traveled (VMTs) – means more emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) that worsen the climate crisis. For California to reach its ambitious goal of “net-zero” CO2 emissions, VMTs must drop deeply and rapidly.

But a recent report from the advocacy group NextGen Policy found that in the last decade VMTs in California have increased and car dependency has gotten worse, largely because the state is still spending too much money on maintaining and expanding freeways and the roads that feed them.

“Despite a clear mandate to reroute transportation policy toward a better future,” the report says, “last century’s pave-the-earth approach is on cruise control in Sacramento.”

An analysis by the Natural Resources Defense Council found that only about a fifth of the state’s transportation budget goes to projects that reduce the need to drive. The advocacy group Transportation for America says California spends eight times as much on roads as it gives to local and regional transit agencies, most of which face a looming “fiscal cliff” that could force deep cuts in service.

Caltrans was created more than 125 years ago as the state Bureau of Highways. Although its mission has expanded to cover mass transit, intercity rail and bike paths, its deeply ingrained road-building culture has been slow to change. Last year Los Angeles transportation planners pulled the plug on Caltran’s planned $6 billion widening of I-710, a landmark cancellation of an expansion amid protests from community and environmental advocates.

“Caltrans is evolving from prioritizing transportation efficiency to a people-first organization,” Gustavo Dallarda, Caltrans district director for San Diego, told KQED News. He said the agency is trying to make transportation part of the community “rather than something that runs through it.”

After the I-710 cancellation, state Transportation Secretary Toks Omishakin told the Los Angeles Times that Caltrans will no longer add freeway lanes solely to accommodate more vehicles. But under the guises of maintenance and safety, expansion continues. Last month, a top Caltrans planner was demoted after she told her supervisor she would file a whistleblower complaint on a project to widen I-80 near Sacramento.

Jeanie Ward-Waller told POLITICO and the Los Angeles Times that Caltrans called the construction “pavement rehabilitation” to get around state and federal requirements for an environmental review and public input, and in her whistleblower complaint she cited other such schemes, including two recently approved “safety” projects that will cost more than $150 million for widened freeways in Santa Barbara and Riverside.

Caltrans’ road-building billions must be redirected to giving Californians sustainable, equitable alternatives to driving and to healing the scars freeways carved in our cities. It’s time to put California’s car culture in the rearview mirror.

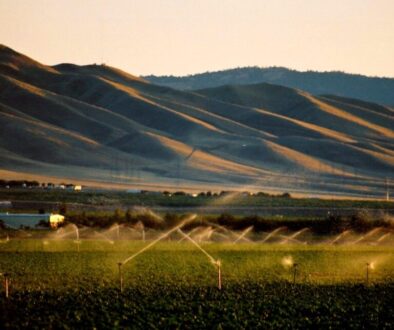

(Featured photo by Sebastian Enrique on Unsplash.)

- Bill Walker has more than 40 years of experience as a journalist and environmental advocate. He lives in California’s San Joaquin Valley.

(Opinion columns published in The New Lede represent the views of the individual(s) authoring the columns and not necessarily the perspectives of TNL editors.)