Puerto Rico’s natural gas buildout may harm those it claims to help

Since 1999, Lissie Aviles, a Catholic nun, has lived in a convent in Cataño, Puerto Rico, a tiny town that borders the Bay of San Juan. The area is home to the world’s largest rum distillery, a Bacardi factory dubbed the “Cathedral of Rum.” Just across the bay, millions of tourists – many from the US mainland – flock to visit Old San Juan’s beaches and historical sites each year.

Cataño is known both as the smallest municipality on the island and as “the town that refused to die,” after it succeeded in fending off an early twentieth-century effort to merge the city with the inland community of Bayamón. The challenges for Cataño residents have persisted — after Hurricane Maria devastated the island in 2017, about 60% of Cataño residents were left homeless. Today, about 46% of the population lives below the poverty line in a US territory lacking full political representation and weighed down by a long legacy of colonization.

Aviles spends much of her time training faith educators in nearby parishes. But in recent years, her work has taken on an additional focus – defending local residents against harmful impacts tied to the island’s intensifying focus on expanding access to liquified natural gas (LNG).

The federal government has earmarked billions of dollars to help stabilize the island’s hurricane-rattled power system, including funding temporary generators powered by natural gas. Additionally, the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) has approved a project to dredge the San Juan Bay beginning in January, allowing the nearby LNG terminal to receive ships carrying six times more LNG than current tankers. And one particularly contentious project is expanding with a new LNG pipeline.

While natural gas is considered the cleanest of fossil fuels because it produces less carbon dioxide than oil or coal, climate scientists say rising use of natural gas is emerging as one of the greatest contributors to human-caused climate change.

Though the stated aim of the LNG buildout is to ensure adequate resources to power the island, LNG imports are bringing methane leaks and diesel exhaust generated by the ships and trucks that transport the fuel, and posing risks associated with potentially explosive infrastructure, say Aviles and other critics. These dangers add to the cumulative risks of existing fossil fuel pipelines, tankers, and other infrastructure that already coexist uneasily with nearby neighborhoods. As they work to heal the wounds wrought by the 2017 hurricane and by Hurricane Fiona in 2022, many Catano residents fear the unintended consequences of an LNG boom.

“This is a community that has a history of abuse and disregard, and part of it has been exposed for years to dangerous contamination,” Aviles said through an interpreter. LNG infrastructure is ”a real threat that is lingering over the people like a time bomb.”

Environmental groups are fighting the Puerto Rico LNG buildout with a string of legal actions. In one such fight, the Center for Biological Diversity and other nonprofits are aiming to block the USACE dredging project, which would remove two million cubic yards of seafloor in the San Juan Bay to allow for expanded LNG shipping in the harbor.

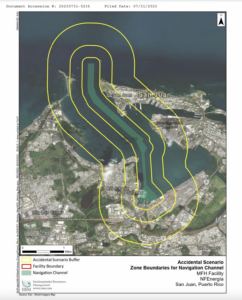

The plaintiffs submitted a filing on Sept. 22 that alleges the USACE is violating the National Environmental Policy Act by failing to account for the project’s potential environmental harms, including impacts on vulnerable coral. The plan to dredge the bay to make way for larger LNG ships would allow the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA) to convert two power plants to LNG instead of retiring them, a move that “could lock in decades of continued fossil fuel use and pollution for local communities,” according to the court filing.

“There’s just a number of safety risks in bringing that amount of LNG into a really busy and densely crowded city,” said Raghu Murthy, a clean energy attorney at Earthjustice, an environmental law nonprofit. “Those folks are very, very scared about what is going to happen if there is an accident, because they’re already living around a lot of industrial activity. This exacerbates all of those concerns.”

The USACE “basically left out all those people living on the western side of the bay” when it outlined areas to be considered for environmental impacts, said Pedro Saadé Lloréns, an adjunct professor at the Environmental Law Clinic of the University of Puerto Rico Law School.

A move to “gasify the grid”?

In the Gulf Coast region of the mainland US, a wave of new and proposed terminals are emerging to export American LNG around the world. But in Puerto Rico, LNG is flowing to the island rather than from it.

Puerto Rico has two LNG import terminals – one at Guayanilla Bay in the southwest part of the island and one at the Port of San Juan in the north.

Shipments of the fossil fuel arrive in the bay on massive tankers, mostly from Trinidad and Tobago, where they are stored on ships called Floating Storage Units that permanently dock at the bay. Later, LNG is transported to the terminals and converted to gas, which generates electricity at local power plants. From July 2021 to June 2022, natural gas-fired power plants generated 43% of Puerto Rico’s electricity, 97% of which is produced with fossil fuels. The US Department of Energy (DOE)’s most recent LNG report states that LNG imports to Puerto Rico from August 2022 through July 2023, before the temporary generation units in San Juan began operating, were 61.1 billion cubic feet, which is comparable to imports for the same time periods the previous two years.

In January, Puerto Rico chose Genera PR, a subsidiary of the New York-based LNG company New Fortress Energy, to operate the island’s fossil fuel-fired power plants for the next decade. PREPA, a public corporation, previously operated the plants. The move puts a private LNG company with an interest in selling natural gas in charge of power generation on the island even as Puerto Rico has committed to reaching 100% renewable electricity by 2050, creating a potential conflict of interest.

Since Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico in 2017, the Biden administration’s investments in rebuilding the territory’s power grid have leaned heavily on fossil fuels, including LNG. The USACE has earmarked $5 billion for a five-year contract to install temporary generation units that can run on both LNG and diesel, a project approved by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and funded by federal disaster relief money approved after Hurricane Fiona hit Puerto Rico last fall.

Since June, three federal government-funded temporary generators connected to the company’s Palo Seco power plant have been providing 150 megawatts of power, “already helping to stabilize the grid and provide reliable, cleaner power for the benefit of Puerto Ricans,” says New Fortress Energy on its website. On September 27, the company began operating a 200-megawatt temporary generation system in San Juan, which is also federally funded.

Puerto Rico’s mayors have shown bipartisan support for portable natural gas generators largely funded by FEMA, and called for the federal government to carry out its original promise to provide the island with at least 700 megawatts of additional power in a September 4 letter to the US Energy Secretary.

While these new fossil fuel-run energy generators are called “temporary,” environmental justice advocates fear they might be here to stay, exacerbating the island’s reliance on fossil fuels and potentially interfering with efforts to bolster renewable solutions to its electrical woes, such as rooftop solar and storage.

“In a lot of ways, sometimes these fossil fuel interests in Puerto Rico are taking advantage of the fact that federal money is available,” said Murthy. “They’re manufacturing a crisis here and they’re using that to gasify the grid.”

“Once that federal money runs out and the government stops paying, it’s going to be on Puerto Ricans to continue fueling these things,” he added.

A FEMA spokesperson said that the temporary generators are critical for reducing the impact of unplanned power outages and are expected to operate until March 15, 2024, “while work to stabilize the existing grid gets on the way.”

The temporary generators at San Juan are being supplied with gas from a new pipeline from the adjacent New Fortress terminal, said a spokesperson for the USACE. Residents’ lack of trust in the industry is due in part to this terminal, which was built by New Fortress in 2019 in a densely populated, disaster-prone urban area without a permit from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). The company claimed that the terminal was outside of FERC’s jurisdiction, in part because it said that a small pipeline connecting the import facility to the power plant does not count as a delivery “pipeline” under the Natural Gas Act. New Fortress did not respond to The New Lede’s request for comment about its LNG projects.

The way the permit was constructed, without a permit requiring the company to consider impacts to surrounding communities and the environment, wouldn’t happen in other parts of the US, said Saadé Lloréns.

“It’s a discriminatory treatment,” he said.

“A very strange, abnormal situation”

The unpermitted LNG terminal spurred a group of faith-based organizations to send a letter to FERC in early 2020 to “convey our fear regarding this new industry being developed so close to our homes and schools, and to request that FERC take an immediate and active role” in supervising the new LNG terminal. The US Court of Appeals in Washington, DC, determined in June 2022 that FERC does have jurisdiction over the terminal, requiring the company to file for a permit through the agency. But the terminal continues to operate.

“We have a very strange, abnormal situation, with a gas terminal being operated without all the environmental and public safety guarantees which are supposed to accompany an LNG terminal,” said Saadé Lloréns.

The LNG tanker traffic comes with risks, including the possibility of accidental explosions or ships running aground. Plus, the LNG ships come in close contact with ships involved in other fossil fuel deliveries, including a Puma operation with an oil dock in Cataño.

“Breakage in the combination of working pipeline and loading and unloading system, rupture in liquid hold, collision and other factors may lead to leakage of liquefied gas, which will result in fire accidents when encountering fire,” warned a 2012 study assessing fire and explosion risk for LNG ships. It estimated that a vapor cloud explosion could injure people standing more than 1,000 meters away from the ship’s center.

“There is no calculation or evaluation of what will happen with the mutual risk with those already-existent [oil] tankers and the LNG tankers,” said Saadé Lloréns.

FERC has confirmed several gaps in the information necessary to assess the New Fortress terminal’s safety, including that the company had not filed an analysis of risks from potential explosions or flammable vapor clouds as of January 2023.

Earthjustice and other groups filed a joint protest to FERC in July regarding the proposal by NFEnergia, New Fortress Energy’s subsidiary, to expand the company’s LNG terminal with a pipeline. Soon after, FERC announced a “determination not to act,” saying that it would not prevent the pipeline’s construction in light of the need for grid stability during the upcoming hurricane season. The groups filed a request for rehearing at the end of August; a FERC letter issued October 2 suggests it has been denied. The groups point to regulatory documents that NFEnergia filed detailing zones around the terminal that could be in danger if an accident occurred.

“They make clear to FERC the densely populated communities, businesses, institutions and infrastructure that could be affected by this Unpermitted LNG Terminal, and exacerbated by the expansion and modification of the LNG Terminal,” wrote the environmental groups in their rehearing request.

Seeing a future in solar

As the conflict over Puerto Rico’s energy future escalates, many point to solar as an alternative that would spare vulnerable communities and make the island resilient to disasters in a way they say fossil fuels never could. A 2023 DOE report found that Puerto Rico was more than capable of meeting its electricity needs through renewable energy, and that residents prefer distributed energy rather than centralized power because it is more resilient to disasters and preserves land for farming.

Even as fossil fuels expand in Puerto Rico, residents’ interest in solar has been surging, with about 85,000 rooftop solar and storage systems on the island as of June. In February, the DOE announced $1 billion to improve energy resilience in vulnerable Puerto Rico communities, including through rooftop solar.

“At the same time one branch of the government is providing $1 billion for rooftop solar and storage, some other branch is providing $5 billion for gas and gas-fired generation,” said Murthy. “It’s interfering with the ongoing [renewable energy] revolution in Puerto Rico.”

(Featured Image: Two LNG tankers docked at the New Fortress Energy LNG terminal. Photo by Jordan Luebkemann, Earthjustice.)