Postcard from California: Why the ‘Erin Brockovich’ Chemical Is Still Unregulated

In 2001, California lawmakers passed a law requiring the state to set a legal limit for a cancer-causing chemical found in the tap water of more than 9 in 10 Californians called chromium-6. The legislation was spurred by the film “Erin Brockovich,” based on the true story of a small town’s David-and-Goliath battle against the state’s largest utility over contamination of its water supply.

In 2001, California lawmakers passed a law requiring the state to set a legal limit for a cancer-causing chemical found in the tap water of more than 9 in 10 Californians called chromium-6. The legislation was spurred by the film “Erin Brockovich,” based on the true story of a small town’s David-and-Goliath battle against the state’s largest utility over contamination of its water supply.

The law ordered establishment of a health-protective standard for chromium-6 in drinking water by 2004. But nearly 20 years after that deadline, the process is still unfinished.

What’s worse, the weak standard recently proposed by the State Water Resources Control Board would leave millions of Californians at increased risk of cancer. And more than a decade after a US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) toxicological review concluded that chromium-6 in drinking water is a likely human carcinogen – a finding reaffirmed last year – there is still no federal standard to protect Americans nationwide.

The tortuous story of California’s long delay and the EPA’s inaction on chromium-6 shows how hard it is to regulate hazardous industrial chemicals in the US. It takes far too long, and a big reason is that polluting industries can stall the process with shady tactics.

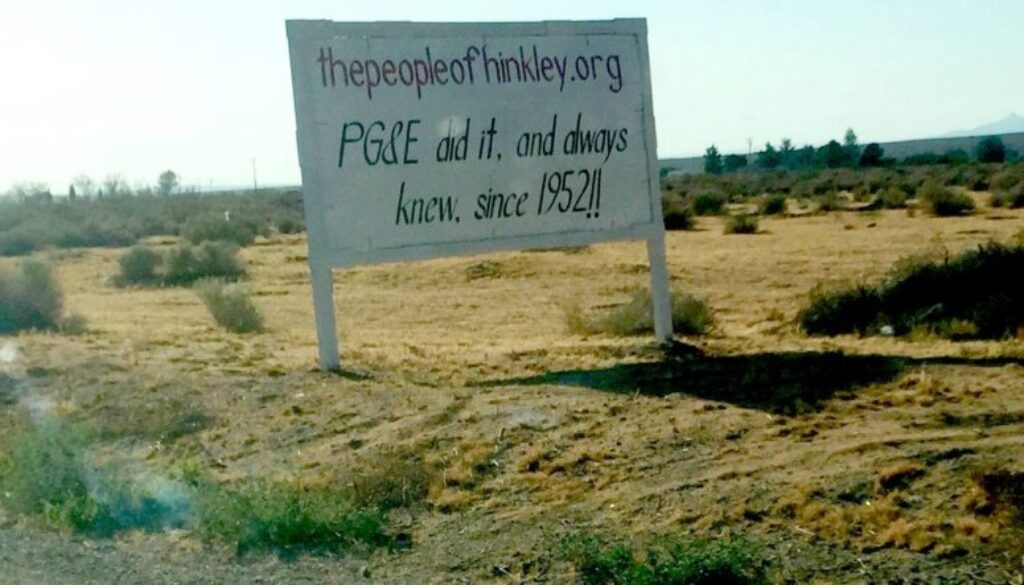

In 1993, investigating unexplained illnesses in Hinkley, Calif., for a Los Angeles law firm, Brockovich uncovered decades of chromium-6 dumping by Pacific Gas and Electric Co. (PG&E). Her firm sued PG&E on behalf of the town, and in 1996 the utility settled out of court for a then-record $333 million. The film based on the case won an Academy Award for Julia Roberts in the title role in 2001.

That same year, the state asked the University of California (UC) to convene an expert panel to assess the chemical’s health hazards. It was well-established that breathing chromium-6 fumes causes lung cancer – the reason California banned its use in chrome plating earlier this year – but there were few human studies of the risks the chemical posed in drinking water. Citing an obscure Chinese study, the panel’s report said a drinking water standard was not needed.

Then a scientist in the state Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA), saw something fishy about the Chinese study. It was a fraudulent “revision” of an earlier study that did find elevated rates of stomach cancer in village residents whose water was contaminated with chromium-6. It distorted the original study’s data to refute the chromium-cancer connection.

The “revision” was written by a San Francisco science-for-hire consulting firm working for PG&E in the Brockovich case – and the firm’s head, who had long worked for big polluters, was an influential member of the UC expert panel. When the deceit and conflict of interest came to light, OEHHA conducted a risk assessment that disregarded the bogus study and the panel’s report.

After reviewing hundreds of studies, OEHHA scientists found that even tiny traces of chromium-6 in drinking water increase the risk of cancer. They issued a public health goal – a non-enforceable contaminant level that would pose negligible risk over a lifetime of exposure.

But after aggressive lobbying by the chromium industry and water utilities, state regulators in 2014 adopted a legal limit 500 times higher than the public health goal. Instead of the lifetime risk of one additional case of cancer in a million people, the state’s limit would pose a risk of one case in 2,000 people.

Even that standard was too stringent to suit the California Manufacturers and Technology Association, which sued to overturn it. In 2017, a Sacramento Superior Court judge agreed, not challenging the science but ruling that the state had failed to show the standard was economically feasible.

OEHHA’s public health goal remained in place, and the agency is currently reviewing new research to see if it needs updating. And last year, the Water Resources Control Board staff proposed the same too-lax legal limit adopted eight years earlier. Gov. Gavin Newsom’s appointees on the board are expected to adopt it next year – 20 years after the original deadline.

The only federal regulation of chromium in drinking water covers both toxic chromium-6 and a benign form called chromium-3. The EPA’s legal limit on total chromium is 10 times higher than California’s proposed limit on chromium-6.

A joint investigation by the nonprofit Center for Public Integrity (CPI) and the PBS Newshour revealed that in 2011, an EPA toxicological review concluded that chromium-6 “likely causes cancer in people who drink it.” But before its finding was made public, the EPA bowed to pressure from the American Chemistry Council (ACC), the powerful lobby for the chemical industry, and agreed to wait for the completion of new industry-funded studies.

To lead those studies, the ACC hired a Texas science-for-hire consulting firm CPI said had a history of “poking holes in research that links chromium to cancer.” One of the firm’s principal scientists previously worked on the PG&E-funded scheme to distort the Chinese study and the industry-funded effort to influence the UC expert panel to say that California didn’t need to regulate chromium-6.

The chemical industry held up the EPA’s review for 11 years. But last year the agency finally released a draft that reaffirmed its earlier finding: Drinking chromium-6 is likely to be carcinogenic to people and is also harmful to the liver and digestive system.

The chemical lobby said the review is “not accurate, unbiased, and reliable.” The American Water Works Association said it “appears to dismiss data collected and funded by ‘industry’ as though the source of funding inherently made the data suspect.”

But it does. Trusting the industry to do unbiased research on hazardous chemicals is like trusting pharmaceutical companies to warn about the dangers of opioids.

The nonprofit online news site ProPublica recently reported that 61 million Americans drink water with unregulated contaminants that may cause cancer or reproductive or developmental harm. Since 1995, the EPA has reviewed data on 35 drinking water contaminants. None have been regulated.

The glacial pace is partly because of the byzantine rulemaking process and also because the EPA and state public health agencies are woefully underfunded. But curbing interference by the chemical industry would be a major step toward speeding the day when all Americans drink clean water.

- Bill Walker has more than 40 years of experience as a journalist and environmental advocate. He lives in California’s San Joaquin Valley.

(Opinion columns published in The New Lede represent the views of the individual(s) authoring the columns and not necessarily the perspectives of TNL editors.)