EPA scores enforcement wins, losses in 2023; announces funding for vulnerable communities

The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) scored both wins and losses in its enforcement of environmental laws for 2023, stepping up fines for polluters and on-site inspections but cleaning up fewer pollutants than it has in a decade, according to the agency’s annual enforcement and compliance report.

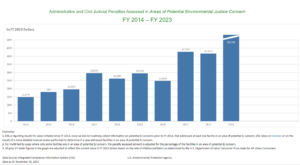

The agency said Monday that it had required polluters to pay more than $704 million in fines, penalties, and restitutions this year, a tally significantly higher than in 2022. However, the agency’s enforcement actions only led facilities to reduce, treat or eliminate about 74 million pounds of pollutants – about 450 million pounds less than in 2015, and the smallest amount since at least 2014.

The EPA said a focus of its work was in communities facing environmental justice concerns; the agency conducted 60% of its on-site inspections in 2023 in such communities, surpassing a goal it had set to achieve by 2026.

The EPA said a focus of its work was in communities facing environmental justice concerns; the agency conducted 60% of its on-site inspections in 2023 in such communities, surpassing a goal it had set to achieve by 2026.

“While our work is not complete, EPA’s revitalized enforcement program is making a positive difference in communities across America, particularly for people living in underserved and overburdened communities that for too long have borne the brunt of pollution,” David Uhlmann, assistant administrator for EPA’s Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance, said in a press release.

In other high points for the year, the agency said its public water system inspections resulted in 150 cases to correct violations – a more than 300% increase over the average for the last decade, the agency said.

And, after losing about 950 jobs following a decade of budget cuts, the agency is now hiring about 300 new positions to boost its enforcement program, the EPA said.

“We’re pleased to see the Environmental Protection Agency staffing up and ramping up enforcement efforts to hold polluters accountable and protect some of our nation’s most vulnerable communities,” said Coby Dolan, the legislative director of the Access to Justice Program at the nonprofit Earthjustice.

The agency needs to do more, however, to address disparate harms faced by frontline communities burdened by pollution, he said.

The EPA results show that the Biden administration is serious about rebuilding EPA’s environmental enforcement and compliance programs, but the enforcement program has become “so degraded that it will take years of sustained funding and political support to turn it around,” said Tim Whitehouse, executive director of the watchdog group Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility and a former senior enforcement attorney at EPA. “I would call this a ‘fragile’ recovery,” he said.

On the heels of the report, the Biden-Harris administration said Tuesday it will provide $600 million in grants over the next three years through an EPA program to help fund local environmental justice projects in communities across the US, including clean-ups, air quality and asthma projects, programs to boost jobs that reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and projects to address illegal dumping.

“These grants could help a nonprofit in, say, Atlanta monitor air pollution levels,” Vice President Kamala Harris said in a press call. “Or they could help a middle school in Indian Country create a summer program to teach young leaders about environmental science.”

The newly announced environmental justice grants will be administered through 11 “well-trusted and well-established community organizations,” she said. The program is expecting to begin opening competitions for funding and awarding grants in summer 2024.

Environmental groups generally applauded EPA’s recent achievements, but some expressed concern that not all of the agency’s recent actions support its environmental justice goals.

Environmental groups generally applauded EPA’s recent achievements, but some expressed concern that not all of the agency’s recent actions support its environmental justice goals.

Last month, the US Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit vacated a 2021 EPA rule that effectively banned the use of the pesticide chlorpyrifos, an insecticide shown to damage children’s brains. The EPA announced Tuesday it plans to allow farmers to use the pesticide on 11 crops, including wheat, soybeans, strawberries, apples, and cotton.

“Harm from chlorpyrifos is generational—children don’t get a do-over on brain development and acute poisonings have a cumulative effect on the long-term health of farmworkers and their families,” said Noorulanne Jan, an Earthjustice attorney. “Pursuing environmental justice means protecting children and farmworker families—EPA should act accordingly.”

To truly promote lasting environmental justice, the EPA needs to shift resources from voluntary programs to regulatory programs that stop pollution from entering the environment in the first place, said Whitehouse. He noted that the EPA recently approved a fuel ingredient with a lifetime cancer risk more than one million times higher than what the agency typically considers acceptable for new chemicals.

“The communities most affected by this dangerous EPA precedent are environmental justice communities,” said Whitehouse. “I am worried on the environmental justice front, EPA is not doing enough to tackle the systemic problems within the agency.”

EWG

EWG