New hope for long-polluted communities, but skepticism of Superfund success remains

By Barbara Reina and Carey Gillam

Jackie Medcalf was a teenager when she moved with her family to a small farm near the San Jacinto River in Harris County, Texas. It felt like a good life, playing in the river and “eating off the land,” as Medcalf describes it.

But the animals quickly grew ill, as did Medcalf, suffering a range of health problems. Her father developed multiple myeloma at the age of 51. Tests of the family’s well water would later reveal contamination with several toxic metals. Testing of the eggs collected from the family’s chickens also found an array of heavy metals. The family was not alone, as others in the area reported similar problems.

There was little doubt about the source of the contamination: The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has designated the San Jacinto River Waste Pits as a Superfund site due to dumping in the 1960s of waste from a paper mill containing carcinogens and other types of toxins. The site has been on the EPA’s “National Priorities List” for cleanup since 2008. But 14 years later, those efforts have yet to be completed.

“For decades my fellow community members have unknowingly recreated around dioxin laden pits,” said Medcalf, now a 37-year-old mother and the founder of a nonprofit that advocates for the cleanup of area contamination. “How many more decades must pass before this disaster is remedied?”

The suffering of the Medcalf family is but one story among far too many that are emblematic of the struggles behind America’s Superfund program, which aims to clean up sites around the country contaminated with a range of dangerous industrial toxins.

In February, the Biden administration said it was earmarking more than $1 billion to help clean up those long-standing hazardous waste sites that are jeopardizing the health of communities around the country. The money is to go to new and continuing projects, and is part of roughly $3.5 billion allocated in President Biden’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law for work at Superfund sites.

The new funding was applauded by community advocates around the country, but also met with some skepticism by those who have been waiting for relief for years, or in many cases, for decades. There are currently more than 1,300 sites around the US on the EPA’s priority list, designated for cleanup under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act of 1980 (CERCLA). But progress has been slow, hindered by a range of bureaucratic hurdles that critics say prioritize politics over public health.

The law allows the EPA to make the companies responsible for the contamination do the cleanup work themselves or reimburse the government for the costs of cleaning up the sites. This “polluters pay” model is a core component of CERCLA. But the complex and costly work required for the cleanups often is slowed by conflicts with the companies deemed responsible for paying for and managing the work and the challenges in trying to eradicate enormous amounts of hazardous waste that have become deeply embedded in soils and sediment.

The lengthy process involved in planning and implementing cleanups in coordination with the companies responsible for the pollution leaves vulnerable people exposed to known health-damaging toxins for far too long, forcing communities to advocate for faster timetables and more stringent cleanup requirements, critics say.

The law gives the EPA latitude to punish companies that don’t comply with EPA orders, including allowances for the recovery of up to three times its costs.

“They (the EPA) have the legal authority, they need the political will,” said Stephen Lester, science director at the Center for Health, Environment & Justice (CHEJ). “They want to be the friend of these companies, not their regulators.”

Millions at risk

Researchers say that living within 1.8 miles of a Superfund site puts people at risk for life-long, adverse health effects. Roughly 21 million people live even closer – within a mile – of a Superfund site, where toxins such as lead, arsenic, and mercury pollute the water, air and soil.

Health risks of close proximity to such hazardous substances include cancers, birth defects, reproductive problems, and genetic mutations, according to the EPA.

The San Jacinto River Waste Pits site is a prime example of the difficulties that come with the Superfund cleanup project. In the mid-1960s, the Champion Paper Mill hired McGinnis Industrial Maintenance Corporation to dispose solid and liquid pulp and paper mill wastes contaminated with dioxins and furans into waste pits on the banks of the San Jacinto River. Two contaminated pits sprawl about 15 acres each, spilling dioxins into the river. Dioxins are highly toxic chemical compounds that can cause cancer, reproductive and developmental problems, damage the immune system, and interfere with hormones.

People living in the area have suffered elevated rates of cancer, including abnormally high incidences of childhood cancers, according to a 2015 assessment by the Texas Department of State Health Services.

For several years, the EPA has been trying to coordinate a cleanup strategy with the two companies deemed responsible for the contamination, working to excavate the contaminated soils, cap or otherwise contain the waste pits, and take other mitigation measures. Some work has been done, but the EPA and the companies involved still have not agreed on a final comprehensive action plan. The latest plan proposed by the companies contained a “serious deficiency”, according to the EPA.

Last month, the EPA sent a letter to the project coordinator for the cleanup work regarding the lack of progress. The agency has given the companies another 90 days to produce a workable plan.

Amid the delays, the community fears contamination continues. A petition to the EPA drawn up by community advocates states that “Time is of the essence.”

“We need the EPA to use every authority granted under CERCLA to move this site to remediation,” the petition states. “The health and wellbeing of our community and Galveston Bay hinges on the successful cleanup of this Site…”

Under fire

The issues seen in Texas are not unique.

The EPA is also under fire for its handling of a Superfund site in Montana where waste from an aluminum company has contaminated groundwater and surface waters with what the EPA calls “contaminants of concern,” including cyanide, fluoride and various metals. The company, Columbia Falls Aluminum Company (CFAC), operated from 1955 and 2009, leaving a legacy of hazardous waste that spreads over more than 900 acres north of the Flathead River.

Testing found multiple contaminants in groundwater in the area, including cyanide, fluoride and metals such as aluminum, arsenic, chromium, copper, iron, lead, nickel, selenium and vanadium, among others, according to the EPA.

The federal government has known for decades that the area was dangerously polluted. In the 1960s, government researchers reported that emissions from the plant were impacting wildlife and in 1988, an EPA-commissioned report confirmed that cyanide, a known serious health risk, and other contaminants were going into the water from the plant. But it was not until 2016 that the site was added to the National Priorities List. It took until 2021for CFAC to finalize a cleanup feasibility study under EPA oversight. The agency then released a proposed cleanup plan in June 2023.

Though long-awaited, the plan is not meeting with community approval. A grassroots organization called the Coalition for a Clean CFAC is petitioning the EPA and Montana Department of Environmental Quality over the plans to handle the toxic waste. The group says the EPA is poised to allow most of the contamination to stay in place behind a concrete wall that would be constructed. The group says the plan would “leave the toxic waste-in-place and restrict future economic redevelopment and human use. Forever.”

“The community has been calling for a complete cleanup including off-site removal for a long time,” said Peter Metcalf, a spokesman for the Coalition for a Clean CFAC.

In California, public health advocates have accused the US Navy and the EPA of failing to deal with the toxic dumping at the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard Superfund site in a way that protects the public.

The shipyard in San Francisco has been on the Superfund list since 1989, contaminated with radioactive waste, pesticides, heavy metals, petroleum fuels, PCBs and other toxins from the naval activities there. While some remediation work has been completed to the EPA’s satisfaction, critics say the work has not eradicated the hazardous waste but has merely capped and covered it up.

Last year, the nonprofit Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER) complained to the Navy’s Office of Inspector General, alleging the Navy has failed to properly inform the public about the dangers of the contamination at the site.

As well, a group called Greenaction for Health and Environmental Justice accuses the Navy and the EPA of violating CERCLA and other laws and says the Navy and EPA have failed to take action at the site that “assures protection of human health and the environment.”

The group wants the EPA to force the Navy to do a “proper cleanup,” said Bradley Angel, Greenaction executive director.

“Success” stories

The EPA points to several of what it calls “success stories” and says that the Superfund cleanups are working to protect human health and the environment, “while also supporting community revitalization efforts and economic opportunities through redevelopment.”

The agency points to a 200-acre former steel company site next to the Delaware River in New Jersey. The industrial work left the soil and water contaminated with heavy metals and buildings on the site were filled with asbestos. The EPA oversaw demolition of 70 buildings and removed underground contamination and dredged both the river and a creek. It counts the site as a success story in part because the site was turned into a light-rail commuter station and parking lot, and a museum was established on the site. The EPA said it also restored the riverfront and opened 34 acres of public greenspace along the river.

One of the largest Superfund sites in the country, the Hudson River PCBs Superfund site is also hailed by the agency as a success story. The agency spent many years working on a plan and has removed 2.75 million cubic yards of river mud dredged from the Hudson River that was contaminated with 310,000 pounds of cancer-causing polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), which were banned in 1977. The EPA said marked it the “largest and most technically complex environmental dredging work ever undertaken in the United States.” The agency is now monitoring the area for “natural recovery.”

Concerns remain about the work, however. An independent study found that dredging the upper Hudson failed to reduce PCB concentrations to the target range set by the EPA. A group called Friends of a Clean Hudson (FOCH) is calling for a pause in the dredging and an adjustment to future remediation goals.

“We’re calling on the agency to step back and see, this is your data, and we feel you’re even more off track than before,” said former EPA Region 2 administrator Peter Lopez, who is now executive director of policy, advocacy and science with a group called Scenic Hudson.

A third EPA five-year review on how the river has been recovering will be released soon, according to EPA Public Affairs Specialist Larisa Romanowski.

Money woes

The Superfund program has long faced money woes, including funding cutbacks, struggles to pry money from “potentially responsible parties” (PRPs), and a failure to properly manage costs.

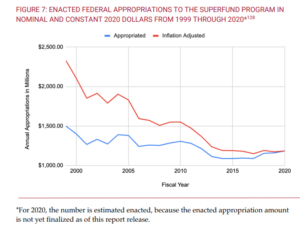

After the expiration of a special polluters tax on the chemical and petroleum industries in 1995, program funding declined to the point that by 2010 the EPA estimated that cleanup costs were outstripping funding, even as the list of sites being added to the program was increasing.

From 1999 to 2020, annual appropriations for Superfund work dropped from $2.3 billion to just under $1.2 billion, resulting in cleanup delays, according to a report by the Public Interest Research Group (PIRG) and Environment America.

During the period from 1999 to 2013, the EPA did not have enough money to pay for about a third of the cleanup work ready to begin, and from 2014 to 2021, the same was true for about one fourth of the projects ready to go, according to the groups.

The outlook is much brighter going forward, however, due not only to the new money earmarked by the Biden administration, but also because of the reestablishment of the polluter pays taxes, which should provide a “steady stream of funding” to the program for at least the next several years, according to an updated report from the groups.

EWG

EWG