Battles brew over radioactive wastewater discharge from shuttered nuclear plants

By Dana Drugmand

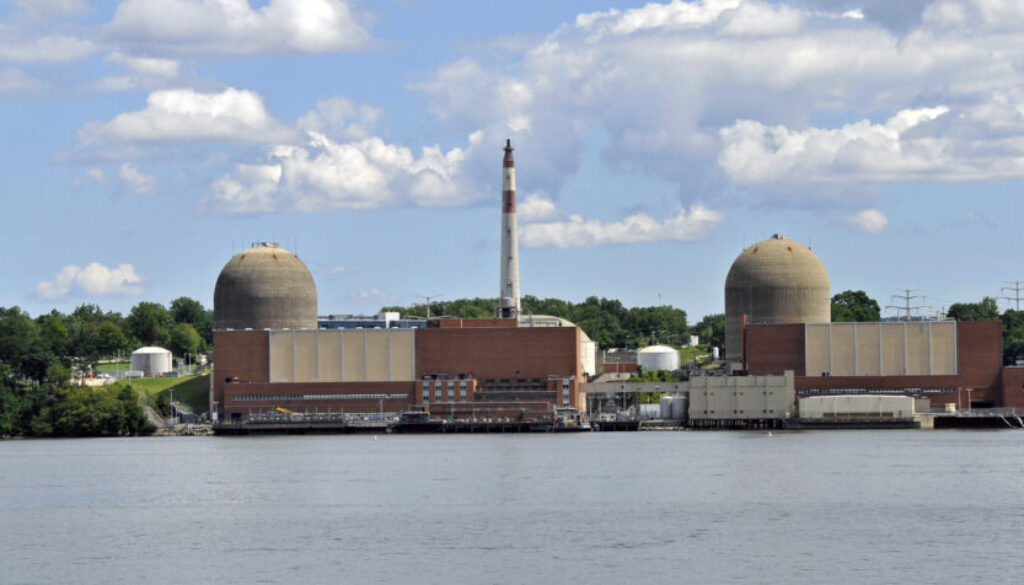

An effort by New York to ban radioactive waste from polluting the Hudson River has embroiled the state in a bitter legal battle emblematic of challenges facing communities across the country as they wrestle with what to do with the waste from shuttered nuclear power plants.

At the heart of the matter in New York is a law enacted last August that aims to block plans by Holtec International to discharge more than one million gallons of radioactive wastewater into the river during the decommissioning of the Indian Point nuclear power plant. The company sued the state in April, arguing that the discharge was allowed under federal regulations, which preempt state regulation.

The state filed a countersuit, asking the US District Court for the Southern District of New York to dismiss Holtec’s claims and validating the state new.

The United States has long had the largest nuclear power plant fleet in the world, with nuclear power accounting for roughly 20% of annual electricity generation from the late 1980s into 2020, according to the US Congressional Research Service. There are currently more than 90 commercial nuclear reactors in operation at 54 nuclear power plants in 28 states. But many have been closed over the last decade, with more scheduled for closure, due to economic challenges and battles with environmental and public health advocates who cite a number of risks associated with the facilities.

The battlegrounds extend far beyond New York. Holtec is facing similar community opposition to its plan to discharge radioactive wastewater from the decommissioning Pilgrim nuclear plant in eastern Massachusetts into Cape Cod Bay, for instance.

“It’s very clear no one wants this radioactive waste in the water,” said Santosh Nandabalan, an organizer with Food & Water Watch who campaigns against the radioactive wastewater dumping. “I think Holtec needs to get with the program now that there’s a law, and we’re going to hold them accountable to it by continuing to use this people power to ensure our Hudson River does not become a dumping ground.”

Holtec spokesman Patrick O’Brien told The New Lede that Holtec’s goal is to “safely decommission these plants and return the property to be economic engines for the communities that they reside in.” He said the company has “been open and forthright… answering questions as they have arisen.”

Opponents to discharging the radioactive wastewater, according to O’Brien, are trying to “push fear over facts.” He said the “reality [is] that you get more radiation from ingesting a banana or brasil nuts that you would from discharge.”

A common practice

Proponents of nuclear wastewater discharge argue that contaminants will be so diluted in the receiving water body that they will pose little if any risk. They say that environmental discharge of radioactive substances happens routinely in the nuclear power industry and can be safely managed.

Radioactive spent fuel from the power plants is generally stored on site in liquid pools or dry casks, and this waste is accumulating by about 2,000 metric tons each year with no permanent repository for burying the waste established.

Water used for cooling and spent fuel storage, contaminated with radioactive substances, also has to be managed and disposed of, and discharging the treated wastewater into local waterways is a common practice when nuclear power plants are operating as well as when they are decommissioning.

The decommissioning plan for the Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant in California, for example, involves discharging treated wastewater into the ocean, while other radioactive waste will be either stored on site or transported off site.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) states on its website that the federal agency “regulates the disposal of radioactive waste” including “transferring the material or waste to an authorized recipient, storing it for decay (decay-in-storage), and safely releasing it into the environment (effluent release). Any disposal method may be chosen if it meets the applicable NRC regulations.” The latter disposal method, while it may technically be considered “safe” according to regulatory authorities, has raised alarm in some communities surrounding decommissioning nuclear plants and the nearby waterways receiving the radioactive discharges.

But opponents to environmental discharges of the waste say regulators fail to take into account long-term, intergenerational toxic exposures to these substances, and how they may interact with other environmental contaminants that the public is exposed to

“There needs to be a complete generational reframing of how we think about releasing these radioactive substances,” said Cindy Folkers, a radiation and health hazard specialist with Beyond Nuclear. “Radiation’s not in a vacuum, and that’s part of the problem. No one is looking at the synergism.”

Arnie Gundersen, chief engineer at FaireWinds Energy and a nuclear industry decommissioning expert, also said that federal regulators are not looking at the complete picture of environmental contamination when authorizing radioactive discharges from nuclear energy facilities.

Wastewater from nuclear power plants contains tritium – a radioactive isotope of hydrogen – which can be hazardous and potentially carcinogenic. Dumping large volumes of this radioactive wastewater into waterways already contaminated with toxins like PFAS or PCBs risks creating even greater contamination issues, he said. He noted that the Hudson River, for example, is known to be polluted with PCBs.

“There’s this thing called synergistic toxicity,” Gundersen said. “The NRC regulations don’t take that into account, and the EPA regulations don’t take that into account.” The science around how tritium may interact with or affect other chemical contaminants is not well understood, which warrants a precautionary approach when it comes to disposing of radioactive wastewater from nuclear plants. “There’s no doubt in my mind there’s not enough science to allow it to be dumped.”

Seeking alternatives

New York’s Indian Point nuclear power plant, located on the east bank of the Hudson River about 25 miles north of New York City, permanently ceased operating in 2021. Holtec, a private equity company and a big player in the burgeoning nuclear decommissioning business, bought the plant with a plan to accelerate its decommissioning – including release 1.3 million gallons of radioactive wastewater into the Hudson.

But when environmental activists learned of the plan, they swiftly mobilized in opposition, pushing the state to pass the law they dubbed “Save the Hudson”.

In Massachusetts, Holtec faces similar backlash with the decommissioning of the Pilgrim nuclear plant into Cape Cod Bay. The company currently lacks legal authority to discharge into the bay and reportedly is considering evaporating the wastewater.

An April 30, 2024 letter from US Sens. Ed Markey and Elizabeth Warren and US Rep. William Keating, sent to Holtec’s president and CEO, states: “There is no question that evaporating wastewater from Pilgrim poses potential health and environmental risks.” The letter urges the company to heed community concerns about releasing the waste into the air or water.

The nuclear wastewater disposal dilemma is not limited to the US. In Japan, releases of treated wastewater into the Pacific Ocean from the Fukushima plant began in March 2024, but the option to discharge the radioactive water into the ocean is highly controversial and the move has prompted China to ban seafood imports from Japan.

According to one expert who studies the environmental consequences of radioactive pollutants in the environment, the wastewater release from Fukushima is not expected to result in any significant impacts for the marine ecosystem.

Jim Smith, a professor of environmental science at University of Portsmouth in the UK, co-authored a paper published in October that notes that it is “common practice for nuclear facilities worldwide to discharge wastewater containing [tritium] into the sea.” Releasing large volumes of water containing small amounts of the radionuclide tritium is generally safe, Smith told The New Lede. “The radiation doses to the public from this release are extremely small – I would call them insignificant,” he said.

Despite such reassurances, it is still “totally understandable” why people are disturbed by the prospect of radioactive water being released into their local environment, said Allison Macfarlane, professor and director of the School of Public Policy and Global Affairs at University of British Columbia, and a former chair of the NRC. “It’s really important for these nuclear companies and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to work with the affected public.”

One disposal option is to package the wastewater and transport it off-site to a licensed treatment facility. This is what NorthStar, another nuclear decommissioning company, did with the Vermont Yankee nuclear plant.

Another alternative for contaminated wastewater is long-term storage before release. Holding contaminated wastewater for 10-20 years allow for the radioactivity to decrease is an alternative to the quick dumping approach, and one that Gundersen says is probably most appropriate for the million-plus gallons of radioactive water at the Indian Point plant in New York. “My recommendation is to store it until you find out the science behind releasing tritium into water that’s already contaminated with PCBs,” he said.

For the Pilgrim nuclear plant in Massachusetts, which Holtec acquired in 2019, the company evaluated alternative wastewater disposal options and concluded that discharge into Cape Cod Bay would be the most convenient and lowest cost disposition method.

Holtec dismissed the option of long-term on-site storage, stating in an evaluation that “impacts to the decommissioning schedule are a factor in the evaluation of alternatives.” Discharging treated wastewater into the bay, according to the company, would be “the most protective of human health and the environment” as any remaining contaminants or radionuclides, like tritium, would be so diluted as to be barely detectable.

Folkers, however, said this argument is misleading. “If something is dilute, that presupposes that it stays that way, and radioactivity moving in the environment doesn’t stay that way.” She said there is “a lot of confusion that swirls around tritium,” which is routinely released into the environment from nuclear power plants at very low doses that have long been considered relatively benign. But emerging science suggests that this radioactive substance may be more hazardous than previously thought, especially for pregnant women and children.

“People who support releasing [tritium] into the environment think that because it has a low-energy beta, it’s safe, but that’s not how radioactivity works,” Folkers said. “What we should be focused on is the longer-term releases, the releases that happened over 40 years, and the intergenerational environmental and health implications, biological implications, of that contamination.”

The NRC states on its website that “any exposure to radiation could pose some health risk,” which may include increased risk of cancer. The agency says it sets dose limits “well below the levels of radiation exposure that cause health effects in humans – including a developing embryo or fetus. The effects of high doses and high dose rates are well understood. Public health research, however, has not established health risks at low doses and low dose rates.”

For Folkers, this limited understanding of the public health impacts of low-level radiation exposures over the long-term is even more reason to be skeptical of assumptions radioactive waste discharging is safe.

“It is becoming more and more evident that we are not looking at radiation exposure in a way that we need to look at it,” she said.

(Featured photo by Tony Fischer.)

EWG

EWG