Worries in wine country: Napa Valley wrestles with chemical contamination controversy

By Shannon Kelleher

Famous for its lush vineyards and cherished local wineries, Napa Valley is where people go to escape their problems.

“When you first get there, it’s really pretty,” said Geoff Ellsworth, former mayor of St. Helena, a small Napa Valley community nestled 50 miles northeast of San Francisco. “It mesmerizes people.”

What the more than 3 million annual tourists don’t see, however, is that California’s iconic wine country has a problem of its own – one that has spurred multiple ongoing government investigations and created deep divisions among residents and business owners, including some who fear the region’s reputation and environment are at risk.

At the heart of the fear is the decades-old Clover Flat Landfill (CFL), perched on the northern edge of the valley atop the edge of a rugged mountain range. Two streams run adjacent to the landfill as tributaries to the Napa River.

A growing body of evidence, including regulatory inspection reports and emails between regulators and CFL owners, suggests the landfill and a related garbage collection, recycling and composting business known as Upper Valley Disposal Services (UVDS) have routinely polluted those local waterways that drain into the Napa River with an assortment of dangerous toxins.

The river irrigates the valley’s beloved vineyards and is used recreationally for kayaking by over 10,000 people annually. The prospect that the water and wine flowing from the region may be at risk for contamination with hazardous chemicals and heavy metals has driven a wedge between those speaking out about the concerns and others who want the issue kept out of the spotlight, according to Ellsworth.

“The Napa Valley is amongst the most high-value agricultural land in the country,” said Ellsworth, a former employee of Clover Flat. “If there’s a contamination issue, the economic ripples are significant.”

Employee complaints

Both the landfill and UVDS were owned for decades by the wealthy and politically well-connected Pestoni family, whose vineyards were first planted in the Napa Valley area in 1892. The Pestoni Family Estate Winery still sells bottles and sells an assortment of wines, including a cabernet sauvignon etched magnum for $400 a bottle.

The family sold the landfill and disposal services unit last year amid a barrage of complaints, handing the business off to Waste Connections, a large national waste management company headquartered in Texas.

Prior to the sale, Christina Pestoni Abreu, who served as chief operating officer for UVDS and Clover Flat, said in a statement that the company’s operations met “the highest environmental standards” and were in full legal and regulatory compliance. Abreu is currently Director of Government Affairs at Waste Connections.

In her statement, she accused Ellsworth and “a few individuals” of spreading “false information” about Clover Flat and UVDS.

But workers at the facilities have said the concerns are valid. In December of last year, a group of 23 former and then-current employees of Clover Flat and UVDS filed a formal complaint to federal and state agencies, including the US Department of Justice, alleging “clearly negligent practices in management of these toxic and hazardous materials at UVDS/CFL over decades.

The employees cited “inadequate and compromised infrastructure and equipment” that they said was “affecting employees as well as the surrounding environment and community.”

Among the concerns was the handling of “leachate”- a liquid formed when water filters through waste as it breaks down, leaching out chemicals and heavy metals such as nitrates, chromium, arsenic, Iron, zinc, and other contaminants.

In the complaint, the employees also cited the use of so-called “ghost piping,” describing unmapped and unquantified underground pipes they said were used to divert leachate and “compromised” storm water into public waterways, instead of holding it for “proper treatment.”

Additionally, there have been allegations of a lack of proper road maintenance leading to runoff of contaminants and improper handling and storage of hazardous materials.

Several fires have broken out at the landfill over the last decade and concerns have also been raised about the facility’s handling of radioactive materials.

Even the “organic compost” the UVDS facility generates and provides to area farmers and gardeners is likely tainted, according to the employee complaint, which cites “large scale contamination” of the compost.

“These industrial sites are affecting the environment and residents of Napa Valley,” former UVDS employee Jose Garibay Jr. wrote in a 2023 email to Napa County officials. “Also, the biggest revenue for the wine country could be tremendously affected; the wine industry, tasting rooms, wineries, hotels, resorts, restaurants, and local businesses.”

Garibay said in his correspondence to county officials that ground water and water pollution stemming from the operations had been happening for years, and he believed his job was terminated in April 2022 because he would not keep quiet about the “unlawful water contamination” as well as fires at the UVDS site.

Abreu did not respond to a request for comment. Other representatives for Clover Flat, UVDS and Waste Management also did not respond to requests for comment.

Toxic PFAS found

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has listed Clover Flat as one of thousands of sites around the country suspected of handling harmful per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS).

After a request from regulators for an analysis of leachate and groundwater samples at the landfill, Abreu reported to the California Regional Water Quality Control Board in 2020 that a third-party analysis had found PFAS in all the samples collected.

PFAS are manmade chemicals that don’t break down and have been linked to cancers and a range of other illnesses and health hazards. Levels of PFOS and PFOA – types of PFAS considered particularly dangerous – were detected in the landfill’s leachate at many times higher than the drinking water standard recently set by the EPA.

In early 2023, the San Francisco Regional Water Quality Control Board sampled a creek downstream from CFL for eight PFAS, identifying multiple PFAS compounds in each sample, according to an email from Water Board inspector Alyx Karpowicz to Waste Connections.

“There are detections in the creek of the same compounds detected at the Clover Flat landfill,” Karpowicz informed the company.

When asked about the results, a spokesperson for the Water Board said the PFAS concentrations in the creek samples were low enough that “chronically exposed biota are not expected to be adversely affected and ecological impacts are unlikely.”

The Water Board’s GeoTracker database, which contains quarterly inspection reports, indicates that PFAS isn’t the only contaminate. Heavy metals are present in “alarmingly high detection” levels at the landfill, said Chris Malan, executive director of the Institute for Conservation Advocacy, Research and Education, a watershed conservation nonprofit in Napa County.

In 2022, the California Sportfishing Protection Alliance (CSPA) sued Clover Flat, alleging since at least January 2021 that landfill operations were engaged in “ongoing and continuous” violations of the Water Pollution Control Act. The organization cited the risk of exposure to heavy metals and other contaminants that it said could cause health problems in people and aquatic animals, including “neurological, physiological, and reproductive effects.”

The case was settled in early 2023, with CFL agreeing to a series of actions, including implementing new erosion control measures, new training for workers to improve pollution control, and required sampling and testing of stormwater. Importantly, Clover Flat agreed to take action if testing showed contaminants above certain levels. The landfill also agreed to pay $125,000 to CSPA for legal fees and ongoing monitoring of CFL’s compliance with the settlement, as well as paying $75,000 to a third-party foundation to fund projects to improve water quality in the Napa River.

“Both UVDS and [Clover Flat Landfill] have no business being in the grape growing areas or at the top of the watershed of Napa County,” said Frank Leeds, former president of Napa Valley Grapegrowers who runs an organic vineyard across from the UVDS composting operation. “There are homes and vineyards all around that are affected by them.”

Regulatory violations

Clover Flat opened in 1963, and together with UVDS provides a range of valuable services to the community, according to the facility websites, including collecting and capturing methane gas to convert to electricity. Working with Pacific Gas & Electric, a Clover Flat “Resource Recovery Park” provides enough energy to power the equivalent of 800 homes. Clover Flat operates with “net zero” emissions, according to the website, employing sustainability practices “which have become the standards for industry.”

Not addressed on the Clover Flat website are multiple recent alleged regulatory violations involving discharges into the streams that run near the landfill and feed the Napa River.

Notice of violations at the landfill have been leveled by multiple agencies.

A joint investigation conducted by the Water Board, the Napa County District Attorney’s Office and California Department of Fish and Wildlife led to the leveling of a civil penalty of $619,400 against the landfill last year.

Among the permit violations alleged was the discharge of 40,000 gallons of “leachate-laden” stormwater into one of the streams and a discharge of “acidic” stormwater into the same stream. Investigators also alleged a “failure to implement effective erosion and sediment controls” and a failure to implement “best management practices for preventative maintenance.”

One 2019 report from a California Department of Fish and Wildlife Officer determined that the landfill had “severely polluted” both streams that flow through the landfill property with “large amounts of earth waste spoils, leachate, litter, and sediment.” There was “essentially no aquatic life present” the investigator noted, citing concerns about “long-term stream pollution” and harmful impacts on multiple other species, including several protected under the state’s Endangered Species Act.

A 2019 email thread to and from state regulatory officials noted “an intentional, illegal discharge of landfill leachate” from Clover Flat into a creek that flows downstream directly into the Napa River. Inspectors additionally noted “improperly managed debris” and said they had been issuing the landfill violations “for months”.

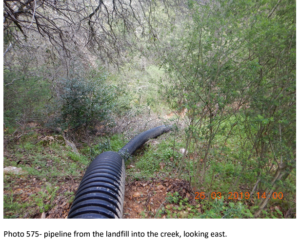

A 2019 “cleanup and abatement order” issued by state officials reported a pipeline running from the landfill directly into the creek. The order demanded the landfill immediately “cease all discharges into the creek.

Discharges from the facilities remained a concern, however, at least as recently as last year. Napa County Solid Waste Program Manager Peter Ex warned county officials in January 2023 that UVDS “may have a discharge into the creek from their wastewater pond in the coming days/week.”

Last fall, a group of Water Board officials visited the landfill to hunt down the “ghost piping” alleged in the worker complaint, reporting in an October 2023 email that they discovered a culvert intercepting the creek and running beneath the access road, “it’s purpose unknown,” as well as a metal pipe in the creek that runs under the access road toward the pond, and “many pipes” going between the containment pond and a stormwater drain. The findings require further investigations, the email said.

There remains an “ongoing investigation” into environmental concerns tied to Clover Flat and UVDS, according to Eileen White, executive director of the San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board.

The board will “summarize our investigation after the investigation is concluded,” she said, adding that they hope to complete it by the end of the summer.

Steven Lederer, Napa County Public Works Director, confirmed a joint probe by the Water Board and the Local Enforcement Agency (LEA). He declined to comment further.

Separate from the environmental probe by state and local officials, the US Justice Department has issued subpoenas for information from UVDS as well as from more than 20 other companies and individuals in the region. That investigation appears to focus on local political connections and contracts, not environmental concerns.

Little public pushback

Ellsworth is among a small group of community members who have tried taking their own actions against UVDS and CFL.

In February 2021, dozens of residents voiced complaints about odors, noise and light pollution from UVDS at a virtual meeting.

Area residents Mathew Smith and his wife Kami Smith joined with other neighbors to file a lawsuit against UVDS and CFL in May 2021, alleging the companies polluted the Napa River and engaged in violations of numerous solid waste, chemical, drainage, discharge, leachate, permit and environmental regulations.

The lawsuit was dismissed shortly after it was filed, however, due to a lack of financial support, according to Mathew Smith. Other area residents, including winemakers, had initially pledged to donate funds for the legal fight, but withdrew that support due to fears of publicity, Smith said.

The Smiths, who live close to UVDS, continue to worry what they might be exposed to, including concerns about exposure to types of PFAS that are known to cause cancer and other illnesses.

“Frankly, we only use our water to shower because we don’t know what’s in it,” said Mathew Smith.

Lauren Pesch, who co-owns a vineyard near UVDS with her father Frank Leeds, said she has deep concerns about water contamination from CFL and has seen pipes from the UVDS property carrying liquid into the creek next to her vineyard.

But the wine industry itself has not expressed public concern, and when asked for comment about the issues, there were no replies from Napa Valley Grapegrowers, Napa Valley Vintners, nor California Certified Organic Farmers.

Winegrowers of Napa County Executive Director Michelle Benvenuto said she was “not knowledgeable enough on the details of this issue” to comment.

Anna Brittain, executive director of the nonprofit Napa Green, a sustainable winegrowing program that lists UVDS as a sponsor, also said she was not aware of concerns about contamination held by any members.

Over a dozen Napa Valley vineyards or wineries did not respond to request for comment from The New Lede or declined to comment.

Ellsworth maintains that Napa Valley’s wine industry prefers any contamination concerns be kept quiet.

“We tried to talk to the Napa Valley wine industry trade organizations. They completely stonewalled us,” he said. “Everybody’s afraid to speak up or is too apathetic or doesn’t want to see it.”

Winemaker Julie Johnson, who farms in the Napa River watershed not far from UVDS does not irrigate most of her land, drawing water as needed from a deep well. Still, she said she is “diligently trying to follow all of the science” surrounding UVDS and CFL.

“I would think that this is a topic that many farming communities –not just in California–are facing,” she said.

(Featured image: Clover Flat Landfill overlooks Napa Valley. Drone photo taken by environmental activist Anne Wheaton.)

(This article was co-published with The Guardian.)

EWG

EWG