“It’s scary”- Scientists finding mounting evidence of plastic pollution in human organs

By Douglas Main

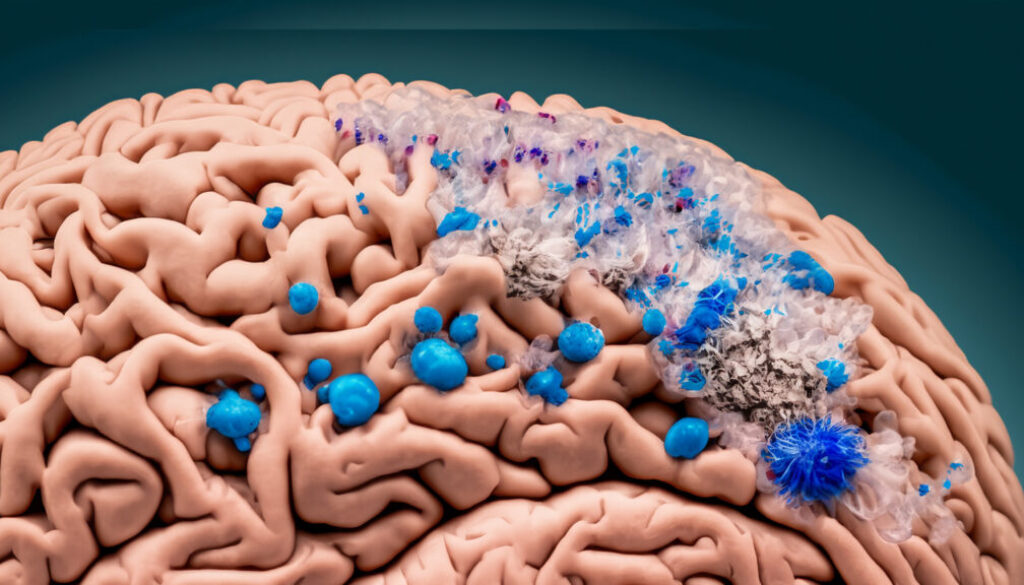

A growing body of scientific evidence shows that microplastics are accumulating in critical human organs, including the brain, alarming findings that highlight a need for more urgent actions to rein in plastic pollution, researchers say.

Different studies have detected tiny shards and specks of plastics in human lungs, placentas, reproductive organs, livers, kidneys, knee and elbow joints, blood vessels, and bone marrow.

Given the research findings, “it is now imperative to declare a global emergency” to deal with plastic pollution, said Sedat Gündoğdu, who studies microplastics at Cukurova University in Turkey.

Humans are exposed to microplastics – defined as fragments smaller than five millimeters in length – and the chemicals used to make plastics from widespread plastic pollution in air, water, and even food.

The health hazards of microplastics within the human body are not yet well-known. Recent studies are just beginning to suggest these particles could increase the risk of various conditions such as oxidative stress, which can lead to cell damage and inflammation, as well as cardiovascular disease.

Animal studies have also linked microplastics to fertility issues, various cancers, a disrupted endocrine and immune system, and impaired learning and memory.

There are currently no governmental standards for plastic particles in food or water in the United States. The Environmental Protection Agency is working on crafting guidelines for measuring them, and has been giving out grants since 2018 to develop new ways to quickly detect and quantify them.

Finding microplastics in more and more human organs “raises a lot of concerns,” given what we know about health effects in animals, studies of human cells in the lab, and emerging epidemiological studies, said Bethanie Carney Almroth, an ecotoxicologist at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden. “It’s scary, I’d say.”

“Pretty alarming”

In one of the latest studies to emerge — a pre-print paper still undergoing peer-review that is posted online by the National Institutes of Health — researchers found particularly concerning accumulation of microplastics in brain samples.

An examination of the livers, kidneys and brains of autopsied bodies found that all contained microplastics, but the 91 brain samples contained on average about 10 to 20 times more than the other organs. The results came as a shock, according to study lead author Matthew Campen, a toxicologist and professor of pharmaceutical sciences at the University of New Mexico.

The researchers found that 24 of the brain samples, which were collected in early 2024, measured on average about 0.5 percent plastic by weight.

“It’s pretty alarming,” Campen said. “There’s much more plastic in our brains than I ever would have imagined or been comfortable with.”

The study describes the brain as “one of the most plastic-polluted tissues yet sampled.”

The pre-print brain study led by Campen also hinted at a concerning link. In the study, researchers looked at 12 brain samples from people who died with dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease. These brains contained up to 10 times more plastic by weight than healthy samples.

“I don’t know how much more plastic our brain can stuff in without it causing some problems,” Campen said.

The paper also found the quantity of microplastics in brain samples from 2024 was about 50% higher from the total in samples that date to 2016, suggesting the concentration of microplastics found in human brains is rising at a similar rate to that found in the environment. Most of the organs came from the Office of the Medical Investigator in Albuquerque, New Mexico, which investigates untimely or violent deaths.

“You can draw a line — it’s increasing over time. It’s consistent with what you’re seeing in the environment,” Campen said.

Many other papers have found microplastics in the brains of other animal species, so it’s not entirely surprising the same could be true for humans, said Almroth, who wasn’t involved in the paper.

When it comes to these insidious particles, “the blood-brain barrier is not as protective as we’d like to think,” Almroth said, referring to the series of membranes that keep many chemicals and pathogens from reaching the central nervous system.

Explosion of research

Adding to the concerns about accumulation in the human body, the Journal of Hazardous Materials published a study last month that found microplastics in all 16 samples of bone marrow examined, the first paper of its kind. All the samples contained polystyrene, used to make packing peanuts and electronics, and almost all contained polyethylene, used in clear food wrap, detergent bottles and other common household products.

Another recent paper looking at 45 patients undergoing hip or knee surgery in Beijing, China, found microplastics in the membranous lining of every single hip or knee joint examined.

A study published May 15 in the journal Toxicological Sciences found microplastics in all 23 human and 47 canine testicles studied, finding that samples from people had a nearly three-fold greater concentration than those from dogs. A higher quantity of certain types of plastic particles — including polyethylene, the main component of plastic water bottles — correlated with lower testicular weights in dogs.

Another paper, which appeared June 19 in the International Journal of Impotence Research, detected plastic particles in the penises of four out of five men getting penile implants to treat erectile dysfunction.

“The potential health effects are concerning, especially considering the unknown long-term consequences of microplastics accumulating in sensitive tissues like the reproductive organs,” said study lead author Ranjith Ramasamy, a medical researcher and urologist at the University of Miami.

Meanwhile, a Chinese group published a study in May showing small quantities of microplastics in the semen of all 40 participants. An Italian paper from a few months prior reported similar results.

A handful of studies have also now found contamination in human placentas. A study that appeared in the May issue of Toxicological Sciences reported finding micro- and nanoplastics in all 62 placental samples, though the concentration ranged widely.

In Italy, researchers followed 312 patients who had fatty deposits, or plaques, removed from their carotid artery. Almost six in 10 had microplastics, and these people fared worse than those who did not: Over the next 34 months, they were 2.1 times as likely to experience a heart attack, stroke, or die.

This explosion of research has been made possible thanks to improved methods for measuring the quantity and type of microplastics present. Campen and colleagues used a technique called pyrolysis–gas chromatography–mass spectrometry to heat up and break down samples into smaller molecular components that are then chemically identified.

“Nowhere left untouched”

The Food and Drug Administration says in a statement on its website that “current scientific evidence does not demonstrate that levels of microplastics or nanoplastics detected in foods pose a risk to human health.”

Still, researchers say that individuals should try to reduce their exposure by avoiding the use of plastic in preparing food, especially when microwaving; drinking tap water instead of bottled water; and trying to prevent accumulation of dust, which is contaminated with plastics. Some researchers advise eating less meat, especially processed products.

Leonardo Trasande, a medical researcher at New York University, said much remains unknown about the impacts of microplastic accumulation in humans. The negative health impacts of chemicals used in plastics, such as phthalates, are better established, though, he said. A study he co-authored found exposure to phthalates has increased the risk of cardiovascular disease and death in the United States, causing $39 billion or more in lost productivity per year.

Microplastic particles can be contaminated with and carry such chemicals into the body. So it’s not just the direct effects of their presence that cause harm. “There may be synergy, as the micro- and nanoplastics may be effective delivery systems for toxic chemicals,” Trasande said.

The American Chemistry Council, which represents plastic and chemical manufacturers, did not directly respond to questions about the recent studies finding microplastics in human organs. Kimberly Wise White, a vice president with the group, noted that “the global plastics industry is dedicated to advancing the scientific understanding of microplastics.”

The United Nations Environment Assembly agreed two years ago to begin working toward a global treaty to end plastic pollution, a process that’s currently ongoing.

Several news reports in the last week suggest that the Biden administration has signaled that the U.S. delegation involved in the discussions will support measures to reduce global production of plastics, which researchers say is critical to getting a handle on the problem.

“There’s nowhere left untouched from the deep sea to the atmosphere to the human brain,” Almroth said.

(A version of this article was co-published by The Guardian.)

(Featured image by Alex Hinton.)

EWG

EWG