“Defend or be damned” – How a US company uses government funds to suppress pesticide opposition around the world

By Carey Gillam, Margot Gibbs and Elena DeBre

By Carey Gillam, Margot Gibbs and Elena DeBre

In 2017, two United Nations experts called for a treaty to strictly regulate dangerous pesticides, which they said were a “global human rights concern”, citing scientific research showing pesticides can cause cancers, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s, and other health problems.

Publicly, the industry’s lead trade association dubbed the recommendations “unfounded and sensational assertions”. In private, industry advocates have gone further.

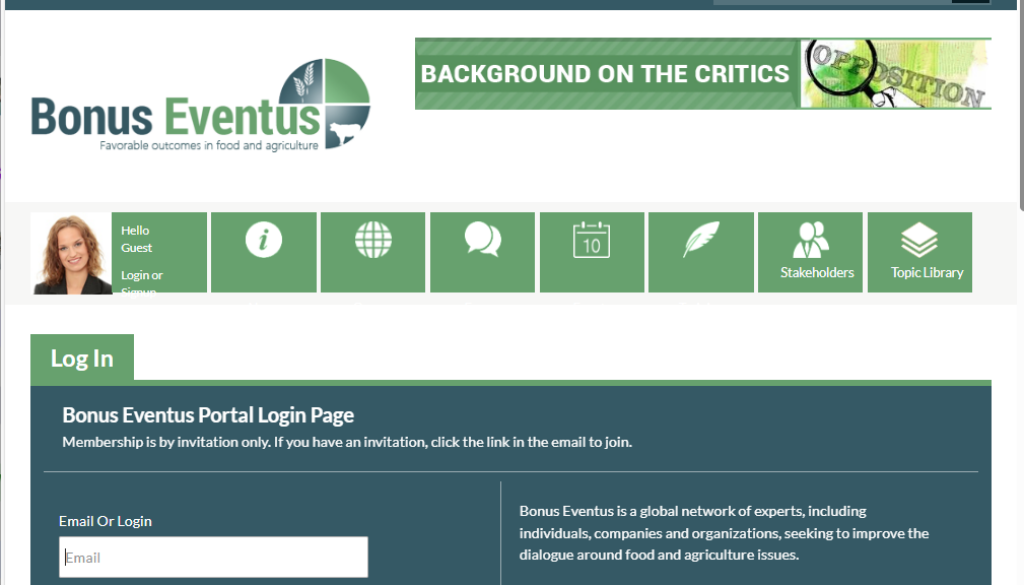

Derogatory profiles of the two UN experts, Hilal Elver and Baskut Tuncak, are hosted on an online private “social network” portal for pesticide company employees and a range of influential allies.

Members of the network can access a wide range of personal information about hundreds of individuals from around the world deemed a threat to industry interests, including US food writers Michael Pollan and Mark Bittman, the Indian environmentalist Vandana Shiva and the Nigerian activist Nnimmo Bassey. Many profiles include personal details such as the names of family members, phone numbers, home addresses and even house values.

The profiling is part of a broad campaign – that was financed partly with US taxpayers dollars – to downplay pesticide dangers, discredit opponents, and undermine international policymaking harmful to the pesticide industry, according to court records, emails and other documents obtained by the non-profit newsroom Lighthouse Reports in an investigative reporting collaboration with The New Lede, the Guardian, and other international media partners.

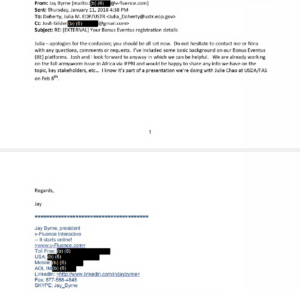

The efforts were spearheaded by a “reputation management” firm in Missouri called v-Fluence. The company, founded by former Monsanto executive Jay Byrne, provides self-described services that include “intelligence gathering”, “proprietary data mining” and “risk communications”.

The revelations demonstrate how industry advocates established a “private social network” to counter resistance to pesticides and genetically modified (GM) crops in Africa, Europe and other parts of the world, while also denigrating organic and other alternative farming methods. More than 30 current government officials are on the membership list of the private network, most of whom are from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Elver, who is now a university research professor and a member of a United Nations food security committee, said public money would have been better spent on scientific research into the health impacts of pesticides than on profiling people such as herself.

“Instead of understanding the scientific reality, they try and shoot the messenger. It is really hard to believe,” she said.

Author Michael Pollan’s profile portrays him as an “ardent opponent” of industrial agriculture and (GM) crops and a proponent of organic farming. His profile includes a long list of criticisms and details such as the names of his siblings, parents, son and brother-in-law.

“It’s one thing to have an industry come after you after publishing a critical article. This happens all the time in journalism,” Pollan said. “But to have your own government pay for it is outrageous. These are my tax dollars at work.”

Records show that Byrne advised US officials and attempted to sabotage opposition to products created by the world’s largest agrochemical companies.

He and v-Fluence are named as co-defendants in a case against the Chinese-owned agrochemical firm Syngenta. They are accused of helping the company suppress information about risks that the company’s paraquat weed killers could cause Parkinson’s disease, and helping to “neutralize” its critics. (Syngenta denies there’s a proven causal link between paraquat and Parkinsons.)

In an emailed statement, Byrne denied the allegations in the lawsuit, citing ‘numerous incorrect and factually false claims,” made by plaintiffs.

When asked about the findings of the investigation, Byrne said that the “claims and questions you have posed are based on grossly misleading representations, factual errors regarding our work and clients, and manufactured falsehoods”.

The company sees its role as “an information collection, sharing, analysis, and reporting provider,” Byrne said.

“Our scope of work that you are questioning is limited to monitoring, research, and trends reporting on global activities and trends for plant breeding and crop protection issues,” Byrne said in his emailed response.

“Under attack”

Byrne joined Monsanto in 1997 amid the company’s rollout of GM crops designed to tolerate being sprayed with the company’s glyphosate herbicides. As director of corporate communications, his focus was on gaining acceptance for the controversial “biotech” crops. He previously held various high-level legislative and public affairs positions at the US Agency for International Development (USAID).

The founding of v-Fluence in 2001 came amid growing public policy battles over GM crops and pesticides commonly used by farmers and other applicators to kill insects and weeds. Mounting scientific evidence has linked some pesticides to a host of health risks, including leukemia, Parkinson’s, and cancers of the bladder, colon, bone marrow, lung, blood cells and pancreas, as well as reproductive problems, learning disorders and problems of the immune system. The concerns about various documented health impacts have led multiple countries to ban or otherwise restrict several types of pesticides.

In a speech Byrne delivered at an agricultural industry conference in 2016, he made his stance clear. He characterized conventional agriculture as being “under attack,” from what he called “the protest industry” and alleged that powerful anti-pesticide, pro-organic forces were spending billions of dollars “creating fears about pesticide use”, GM crops and other industrial agriculture issues.

“We’re almost always cast as the villain in these scenarios,” he told conference attendees. “And so we need to flip that around. We need to recast the stories that we tell in alternative ways.”

While the company’s early clients included Syngenta and Monsanto, it later secured government funding as part of a contract with a third party. Public spending records show the USAID contracted with the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), which manages a government initiative to introduce GM crops in global south countries. In turn, IFPRI paid v-Fluence a little more than $400,000 from roughly 2013 through 2019 for services that included counteracting critics of “modern agriculture approaches” in Africa and Asia.

As part of the subcontract, v-Fluence was to set up the “private social network portal” that would, among other things, provide “tactical support” for efforts to gain acceptance for GM crops in those countries.

The company then launched a platform called Bonus Eventus, named after the Roman god of agriculture whose name translates to “good outcome”.

The individuals profiled in the portal include more than 500 environmental advocates, scientists, politicians and others seen as opponents of pesticides and GM crops.

The individuals profiled in the portal include more than 500 environmental advocates, scientists, politicians and others seen as opponents of pesticides and GM crops.

Details in the profiles appear to be drawn from a range of online sources, with many of the profiles including disparaging allegations authored by people funded by, or otherwise connected to, the chemical industry. Early versions of the profiles were compiled by Academics Review, a nonprofit created with the involvement of Monsanto and Byrne.

Today, Bonus Eventus counts more than 1,000 members, and access is by invite only. Members include executives from the world’s largest agrochemical companies and their lobbyists, as well as academics, government officials, and high profile policymakers such as the Trump administration’s ambassador to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization and an agricultural research advisor to USAID.

A profile of a London-based research professor who has spoken out against agrochemical companies and GM crops contains several deeply personal details of his life unrelated to his positions on crops or chemicals. The profile describes a wife who died of “suicide-related complications” after discovering an extra-marital affair by her husband and following a “23-year struggle with depression and schizophrenia…”

A profile of a prominent US scientist that is laden with critical commentary includes details about a 33-year-old traffic violation and the scientist’s spending on political campaign contributions, along with a personal cell phone number (that had the last digit wrong), and the scientist’s former home address.

An Indiana pediatric health researcher who studies pesticide impacts on babies is also profiled. The information lists a home address – along with the property’s approximate value – and the names and other details of his wife and two children.

Many profiles include “Criticisms” sections that include information provided by people and organizations funded by, or otherwise connected to, the chemical industry.

A profile of former New York Times food writer Mark Bittman, a critic of industrial agriculture, is 2,000 words long and includes a description of where he lives, details of two marriages and personal hobbies, and an extensive Criticisms section.

“It’s filled with mistakes and lies,” Bittman said of the profile about him. Still, he said, the fact that he is profiled is far less of a concern than the larger context in which the profile exists.

Bittman said that it was a “terrible thing,” for taxpayer dollars to be used to help a PR agency “work against sincere, legitimate, and scientific efforts to do agriculture better.”

“The fact that for well over a century the government has steadfastly supported industrial agriculture both directly and indirectly, at the expense of agroecology is a direct roadblock in the face of efforts to produce nutritious food that’s universally accessible while minimizing environmental impact. That’s sad, tragic, malicious, and wrong.”

Both Lighthouse Reports and an author of this article, Carey Gillam, are also profiled on the platform.

“Collecting personal information about individuals who oppose the industry goes way beyond regular lobbying efforts,” said Dan Antonowicz, an associate professor at Wilfrid Laurier University in Canada who researches and lectures about corporate conduct. “There is a lot to be concerned about here.”

When contacted by reporters, some people listed as Bonus Eventus members said they had not signed up for membership themselves, or were not aware of the content. One said they would cancel their membership.

CropLife International, the preeminent advocacy group for agricultural pesticide companies, said it would “be looking into” the issues raised in this piece, after reporters asked about the dozens of CropLife employees around the world who are listed as members of Bonus Eventus.

Actions in Africa

V-Fluence, and Byrne personally, have developed extensive connections with government officials who he has advised on attempts to introduce pesticides regulations outside the US.

In 2018 Byrne attended a meeting with the US Trade Representative to discuss “concrete and actionable ways to assist” the agency in its pesticide policies. Following the meeting, the two were invited to meet with the government’s chief agricultural trade negotiator.

Around the same time, Byrne was invited by the USDA to advise an interagency group tasked with limiting international rules which would reduce pesticides. Byrne instructed the group on how to combat efforts to enact stricter pesticide regulations, and referred to a “politicized threat” from the “agroecology movement.”

A key region for v-Fluence work has been Africa. According to the government contracts, v-Fluence was to work with USAID’s program to elevate pro-GM crop messaging in Africa and counter GM opponents. It focused in particular on Kenya.

A key region for v-Fluence work has been Africa. According to the government contracts, v-Fluence was to work with USAID’s program to elevate pro-GM crop messaging in Africa and counter GM opponents. It focused in particular on Kenya.

Byrne denies that v-Fluence has any past or current contracts with the US government. He said the US funds “other organizations with whom we work,” and over more than 20 years “we’ve had multiple projects funded by the US and other governments.”

But he also said that over more than 20 years “we’ve had multiple projects funded by the US and other governments which have all been satisfactorily completed…” and that the US funds “other organizations with whom we work.”

Opposition to GM crops and pesticides has been strong in Kenya, where around 40% of the population works in agriculture. Kenyan farmworkers use many pesticides that are banned in Europe and are routinely exposed to these products, often without adequate protective equipment or access to healthcare.

Roughly 300 African individuals and organizations, mainly in Kenya, are profiled on Bonus Eventus.

Bonus Eventus lists more than 30 Kenyan members with access to its private network, more than any other country outside North America. Members from Kenya include a high-ranking official at the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries, and a former chief executive of the National Biosafety Authority.

As part of its Kenya campaign, Byrne and v-Fluence were involved in efforts to undermine a conference that was to be held in Nairobi in June 2019, organized by the World Food Preservation Center, an organization which provides education on agricultural-technology in developing countries. Scheduled speakers included scientists whose work has exposed the health and environmental impacts of pesticides, and it came as Kenyan lawmakers were about to launch a parliamentary inquiry into hazardous pesticides.

Records show that in early February 2019, Byrne sent his weekly newsletter to members of Bonus Eventus. The newsletter warned that speakers of the upcoming conference included “anti-science critics of conventional agriculture”, and that “promotional materials include claims that GMOs and pesticides may cause cancer and other diseases”. The email mentioned the conference’s sponsors and linked to the Bonus Eventus profile of the World Food Preservation Center.

The day after he sent the email, prominent members of the Bonus Eventus network took action.

Margaret Karembu, an influential Kenyan policy maker and early member of Bonus Eventus, sent an email alert to a group that included agrichemical employees and USDA officials, many of whom were also members of Bonus Eventus.

“[The pesticides conference] is a big concern and we need to strategize,” Karembu wrote, in an email thread that included discussion about how to “neutralize the negative messaging” of the conference, as one participant described. An official from Bayer, which acquired Monsanto and its pesticide and GM crop businesses in 2018, wrote back to Karembu and others, including a USDA officer, agreeing and suggesting a meeting to “plan mitigation strategies”. (Bayer said it does not work with v-Fluence and its employees don’t use the Bonus Eventus platform.)

Just days later, the organizers of the conference received emails informing them that their funders were pulling out. Martin Fregene, Director of Agriculture and Agro-Industry at the African Development Bank (AfDB), wrote to them: “I am afraid the aforementioned conference is one-sided and sends a wrong message about the AfDB’s position on agricultural technologies approved for use by regulatory bodies.”

Just days later, the organizers of the conference received emails informing them that their funders were pulling out. Martin Fregene, Director of Agriculture and Agro-Industry at the African Development Bank (AfDB), wrote to them: “I am afraid the aforementioned conference is one-sided and sends a wrong message about the AfDB’s position on agricultural technologies approved for use by regulatory bodies.”

The next week, Byrne sent a news alert to his network telling them the AfDB and another sponsor had withdrawn their support of the conference. He later shared the information personally with select employees at USAID and USDA.

Byrne said he had no involvement in the loss of funding for the conference.

Neither USDA nor USAID responded to questions about the conference.

A spokesperson for AfDB said that the bank’s senior management had taken the decision to withdraw funding from the conference after they were contacted by Syngenta, which expressed concerns that the conference was “one-sided”.

The director of World Food Preservation Centre, Charles Wilson, who is a former research scientist at the USDA said he had felt “unseen forces” operating against the conference, but was surprised to learn the details.

“By targeting certain speakers as ‘anti-science,’ this firm appears to be borrowing from an old industry playbook—to attempt to squash legitimate areas of scientific inquiry before they take root,” he said.

Dr Million Belay, general coordinator of the Ugandan non-profit Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa, who was set to speak at the conference, said the findings were “deeply concerning”, describing them as a “blatant attempt to silence and discredit movements advocating for Africa’s food sovereignty.” Bonus Eventus has created profiles on both Belay and AFSA.

In addition to attempting to undermine the conference, v-Fluence associates and Bonus Eventus members have sought to spread disputed claims about pesticides and attempts to limit their use.

In 2020, a petition to ban hazardous pesticides was resubmitted to the Kenyan parliament. At the same time, a stream of articles authored by Bonus Eventus members started circulating about the supposed devastation that the proposed ban would wreak on Kenya’s food security.

In February 2020, for instance, James Wachai Njoroge, who is currently listed as senior counsel on v-Fluence’s website, published an article on the “European Scientist” website with the headline, “Europe’s anti-science plague descends on Africa”. He argued that “European activists are putting lives at risk in East Africa, turning a plague of insects into a real prospect of widespread famine.”

Njoroge’s articles were reposted on several leading climate-denial websites, and articles authored by Bonus Eventus members making the same claims were published in US papers including the Wall Street Journal and Town Hall.

Hans Dreyer, the former head of crop protection at the Food and Agriculture Organization, said that the articles were “utterly biased and highly misleading” and appeared to be attempts to discourage new pesticide regulation.

The Kenyan parliament ordered several government agencies to conduct a wide ranging review of the country’s pesticides regulations, but the process stalled. More than 20 pesticides banned in Europe remain common in Kenya.

“Defend or be damned”

A lawsuit naming Byrne and v-Fluence as co-defendants with Syngenta was filed in Missouri by a woman and her son – Donna and James Evitts – who both suffer from Parkinson’s disease and claim it is linked to decades of use of the herbicide paraquat on their family farm.

The suit contains specific allegations about the role of v-Fluence in hiding the dangers of paraquat, which has been banned in the European Union, the UK, China and dozens of other countries, though not in the US. There have been several studies linking paraquat to Parkinson’s disease, one of the most recent was published in February in the peer-reviewed International Journal of Epidemiology.

The Evitts lawsuit is one of thousands of cases brought by people alleging they developed Parkinson’s from using Syngenta’s paraquat products. The first US trial is scheduled to get underway in February.

Donna’s husband, George Evitts, also had Parkinson’s and died in 2007 at the age of 63. He had sprayed paraquat around his farm from 1971 to shortly before his diagnosis and death, according to the lawsuit. Donna was diagnosed with Parkinson’s two years after her husband died. Their son, who grew up on the farm, was diagnosed with the same disease in 2014.

The lawsuit cites sealed court records in alleging that Syngenta signed a contract with v-Fluence in 2002 to help the company deal with negative information coming to light about its paraquat herbicides. The lawsuit alleges v-Fluence went on to help Syngenta create false or misleading online content that was “Paraquat-friendly” used search engine optimization to suppress negative information about paraquat in Internet searches and investigated the social media pages of victims who reported injuries to Syngenta’s crisis hotline.

According to the lawsuit, in September 2003 Byrne traveled to Brussels to meet with Syngenta executives where they agreed to protect paraquat products from mounting concerns and regulatory actions. The meeting participants agreed to adopt an approach of “defend or be damned,” the lawsuit alleges.

One of the alleged v-Fluence jobs was to develop a website called the “Paraquat Information Center” at paraquat.com that carried a reassuring message about the safety of paraquat and asserted there was no valid scientific link between the chemical and Parkinson’s disease. The site had various featured articles encouraging paraquat use, such as “Why Africa needs paraquat.”

The website did not have a Syngenta branded logo as its other web pages did, and it operated with a domain that was separate from Syngenta. It was only identified as affiliated with Syngenta in a small font at the very bottom of the website. It was not until this year – as litigation against the company accelerated – that Syngenta brought the website under its company web address and added its logo to the top of the page, making it clear the information was coming from Syngenta.

The New Lede and the Guardian have previously revealed that Syngenta’s internal research found adverse effects of paraquat on brain tissue decades ago but the company withheld that information from regulators, instead working to discredit independent science linking the chemical to brain disease and developing a “SWAT team” to counter critics. In its response to those stories, Syngenta asserted that no “peer-reviewed scientific publication has established a causal connection between paraquat and Parkinson’s disease.”

When asked for comment, Syngenta denied the allegations made in the Evitts lawsuit and said scientific studies “do not support the claim of a causal link between exposure to paraquat and the development of Parkinson’s disease.” The company did not answer questions about Bonus Eventus and v-Fluence, saying it would address those claims in court.

In a letter sent by Byrne’s lawyer to Evitts’ lawyers in response to a subpoena for v-Fluence records, the lawyer confirmed that v-Fluence had done work for Syngenta for more than 20 years, but said “Syngenta never engaged v-Fluence to perform any work on Paraquat other than to monitor publicly available information, provide benchmark assessments of content and stakeholder sources, and to provide supplemental contextual analysis”.

Other than saying the lawsuit claims are false, Byrne declined to comment about the pending litigation.

“Really scary”

In 2020, the USDA contracted with a “strategic communications firm” called White House Writers Group (WHWG), in an agreement worth up to $4.9 million. It was part of a USDA strategy to undermine Europe’s Farm to Fork, a environmental policy which aimed to reduce pesticide use by 50% by 2030, which was drastically watered down following heavy industry lobbying.

V-Fluence was to provide “data” services as part of the WHWG contract, which also included access to Bonus Eventus, according to records obtained from the USDA. The contract does not specify how the money was to be divided between the firms.

When asked about the contract, the USDA confirmed that its Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS) entered into a “blanket purchase agreement” with the White House Writers Group that expires in November 2025. Only one “call order” for a payment on the contract has been placed and that was under the Trump administration, the USDA said. Public records suggest that payment was for $50,000.

FAS is “currently reviewing” the blanket purchase agreement, USDA said.

Clark Judge, managing director of White House Writers Group, said his organization had tried to revive the contract, to no avail. He stated that “Bonus Eventus was, and I presume still is, an online community for scholars, journalists, and the like who share perspectives and information on agricultural topics.”

When asked about the findings of this investigation, Byrne said his organization has not engaged in any “unethical, illegal, or otherwise inappropriate outreach, lobbying or related activities… of any kind.”

Some experts say they are disturbed by the US government’s association with v-Fluence.

“I don’t think most people realize the degree of corporate espionage and USDA’s complicity with it,” said Austin Frerick, who served as co-chair of the Biden campaign’s Agriculture Antitrust Policy Committee and recently authored a book about concentration of power in the food system. “The coordination here – the fact that USDA is part of this – is really scary.”

Bonus Events has been active in recent days.

Five days before this story was published, after the reporting team asked Byrne and others for comment, the Bonus Eventus portal alerted members to this upcoming investigative reporting project. They provided members with an article describing this project as as “an ethical trainwreck with no concept of journalistic integrity.”

(See the media library for this story with downloadable documents.)

(Margot Gibbs and Elena DeBre are with Lighthouse Reports, a Netherlands-based investigative journalism collaborative.)

(A version of this article was co-published by The Guardian.)

(Featured photo is an image from the Bonus Eventus portal.)

EWG

EWG

October 1, 2024 @ 4:22 am

Great article, keep going folks. It’s hard I know, when all you are revealing is things that are obvious. Getting this news down to citizen level, along with presenting the alternative food choices needs collaboration. The days of Empire are not over

AJ

Devon, UK

September 29, 2024 @ 11:28 am

Monsanto was run by a CIA agent during the 1980. This may have been the case during the late 60s and 70s as well. In the 80s I researched the group trying to put a natural gas pipeline through the state of Vermont, down through Massachusetts and Connecticut. It wasvat that time we unearthed the CIA tie. It was in his Who’s Who bio! I think it is likely that the Agency infiltrated the USDA and controls USAID as well. Given the link between the part of the chemical industry and petrochemicals (fertilizer), it’s a sure bet that a corporate interlock analysis with deep bios on the heads of the corporations and their boards would triangulate the forces involved in the smear campaign.