Hydrogen hubs test new federal environmental justice rules

A massive push for hydrogen energy is one of the first test cases of new federal environmental justice initiatives. Communities and advocates so far give the feds a failing grade.

By Kristina Marusic and Cami Ferrell

(This is part 1 of a 2-part series originally published at Environmental Health News.)

On a rainy day in September, Veronica Coptis and her two children stood on the shore of the Monongahela River in a park near their home, watching a pair of barges laden with mountainous heaps of coal disappear around the riverbend.

“I’m worried they’re not taking into account how much industrial traffic this river already sees, and how much the hydrogen hub is going to add to it,” Coptis said.

Coptis lives with her husband and their children in Carmichaels, Pennsylvania, a former coal town near the West Virginia border with a population of around 434. The local water authority uses the Monongahela as source water. Contaminants associated with industrial activity and linked to cancer, including bromodichloromethane, chloroform and dibromochloromethane, have been detected in the community’s drinking water.

Coptis grew up among coal miners, but became an activist focused on coal and fracking after witnessing environmental harms the fossil fuel industry caused.

Now, she sees a new fight on the horizon: The Appalachian Regional Hydrogen Hub, a vast network of infrastructure that will use primarily natural gas to create hydrogen for energy. Part of the new Appalachian hydrogen hub is expected to be built in La Belle, which is about a 30 minute drive north along the Monongahela River from her home.

“I have a lot of concerns about how large that facility might be and what emissions could be like, and whether it’ll cause increased traffic on the river and the roads,” said Coptis, who works as a senior advisor at the climate advocacy nonprofit Taproot Earth. “I’m also worried that because this will be blue hydrogen it will increase demand for fracking, and I already live surrounded by fracking wells.”

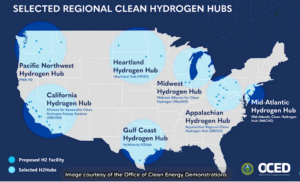

The Appalachian Regional Hydrogen Hub is one of seven proposed, federally funded networks of this type of infrastructure announced a year ago — an initiative born from the Biden administration’s 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. The hydrogen created by the hubs using both renewable and fossil fuel energy will be used by industries that are difficult to electrify like steelmaking, construction and petrochemical production.

The hubs support the administration’s objective of reaching net-zero carbon emissions nationwide by 2050 and achieving a 100% “clean” electrical grid by 2035. All seven hydrogen hubs, which are in various stages of development, but mostly in the planning and site selection phases, are considered clean energy projects by the Biden administration, including those that also use fossil fuels in production.

In March and May, Coptis attended listening sessions hosted by the US Department of Energy (DOE), which is overseeing the hubs’ development and distributing $7 billion in federal funding for them, alongside representatives from industrial partners for the project. She hoped the sessions would provide answers — like exactly where the proposed facilities would be and what would happen at them — but she left with even more questions.

The initial applications from industrial partners to DOE, which included timelines, estimated costs, proposed location details and estimates of environmental and health impacts, were kept private by the agency despite frequent requests from community members to share those details.

“The Department of Energy and the companies involved have not been transparent,” Coptis said. “It’s not possible for communities to give meaningful input on projects when we literally don’t know anything about them.”

In 2023, the Biden administration passed historic federal policies directing 80 agencies to prioritize environmental justice in decision-making. The DOE pledged to lead by example with the seven new hydrogen hubs — but so far that isn’t happening, according to more than 30 community members and advocates. They said details remain hazy, public input is being planned only after industry partners have already received millions of dollars in public funding, and communities don’t have agency in the decision-making.

“The promises DOE has made are just not being met, according to their own definitions of what environmental justice looks like,” said Batoul Al-Sadi, a senior associate at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), a national environmental advocacy group that’s been pushing for increased transparency for the hydrogen hubs.

The EHN investigation also found:

- In initial listening sessions for the hubs, 95 of 113 public comments submitted voiced some opposition to the projects.

- 49 of 113 comments submitted during the listening sessions expressed concern about a lack of transparency or meaningful community engagement.

- More than 100 regional and national advocacy groups have sent letters to the DOE requesting increased transparency and improvements to community engagement processes.

- Communities do not have the right to refuse the hydrogen hub projects if the burdens prove greater than the benefits.

- The DOE is failing to adhere to its own plans for community engagement, according to experts and advocates.

“Right now the [federal environmental justice] regulations are in the best place they’ve ever been,” said Stephen Schima, an expert on federal environmental regulations and senior legislative counsel at Earthjustice. “Agencies have an opportunity to get this right… it’s just a matter of implementation, which is proving challenging so far.”

In response to questions about transparency and community engagement, the DOEsaid it was “focused on getting these projects selected for award negotiation officially… Once awarded, DOE will release further details on the projects.”

Residents of the seven hydrogen hub communities fear that once millions of dollars in federal funding have already been distributed for these projects, their input will no longer be relevant.

The Appalachian and California hubs both received $30 million and the Pacific Northwest hub received $27.5 million in initial funding from the federal government in July. Funding for the other four hubs is still being processed. In total, the seven planned hydrogen hub projects are slated to receive $7 billion in federal funding.

Jalonne White-Newsome, federal chief environmental justice officer at the White House Council on Environmental Quality, said she’s aware that communities are frustrated about the hydrogen hubs.

“I spend a lot of my time working with our partners at the Department of Energy [and other federal agencies], making sure we support the safe deployment of these different technologies,” White-Newsome said. “I continue to hear in many different forms the concerns that communities have — that there is not transparency, there’s not enough information, there’s fear of the technology.”

“I understand all of those concerns,” White-Newsome said, adding that the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council had established a work group of environmental justice leaders across the country to address carbon capture technologies and hydrogen, and was working with an internal team, including federal agency partners at the DOE, “on how to address all of the issues that have been raised by this body.”

Advocates fear these measures won’t do enough.

“Even if this was the best, non-polluting, most renewable green energy project to come to Appalachia, this process does not align with environmental justice principles,” Coptis said.

Environmental justice and pollution concerns

The hydrogen hubs were pitched as a boon to environmental justice communities that would bring jobs and economic development, cleaner air from reduced fossil fuel use and the promise of being central to America’s clean energy transition.

But more than 140 environmental justice organizations have signed public letters highlighting the ways hydrogen energy could prolong the use of fossil fuels, create safety hazards and worsen local air pollution, according to a report by the EFI Foundation.

The Mid-Atlantic and Midwest hubs plan to use renewables and nuclear energy in addition to fossil fuels, while the California, Pacific Northwest and Heartland hubs plan to use combinations of renewables, biomass and nuclear energy. The Appalachian and Gulf Coast hubs plan to use primarily fossil fuels.

Hydrogen hubs are dense networks of infrastructure that will span large regions. Many hydrogen hub components are being planned in communities that have historically been overburdened by pollution, particularly from fossil fuel extraction, so they can take advantage of that existing infrastructure.

For example, Houston’s Ship Channel region, California’s Inland Empire, and northwest Indiana all include environmental justice communities that are tentatively expecting hydrogen hub infrastructure, and all three regions routinely rank among the worst places in the country for air pollution.

DOE has said projects will only be awarded if they demonstrate plans to minimize negative impacts and provide benefits for environmental justice communities, but so far communities expecting hydrogen hubs say they haven’t seen information about how project partners plan to do this, though some information has been provided in California’s community benefits plan.

Communities are worried the hubs will add new industrial pollution sources to already-polluted communities, while data on the cumulative impacts from existing and expanded networks of energy infrastructure remains scarce.

Concerns about health risks are especially acute around the Appalachian and Gulf Coast hubs because of their planned reliance on fossil fuels. Concerns included new emissions from truck and barge traffic, the potential use of eminent domain to seize private property for pipelines, the risk of pipelines exploding or leaking and increased nitrogen oxide emissions from the eventual combustion of hydrogen fuel, which contributes to higher levels of particulate matter pollution and ozone. Exposure to these pollutants are linked to harmful health effects including increased cancer risk, respiratory and heart disease, premature birth and low birth weight.

There are also concerns about these hubs’ reliance on carbon capture and storage technology, which is required in order to convert fossil fuels into hydrogen but won’t be required for hubs using non-fossil fuel feedstocks.

Carbon capture technology is controversial, as many experts and advocates consider it a way to prolong the use of fossil fuels, and have expressed how the technology could actually worsen climate change due to high energy consumption and leaks. Because captured CO2 contains toxic substances, like volatile organic compounds and mercury, the technique can pose risks to groundwater, soil and air through leaks.

Just last month, officials reported that the first commercial carbon sequestration plant in Illinois sprung two leaks this year under Lake Decatur, a drinking water source for Decatur, Illinois. The company that owns the plant, ADM, didn’t tell authorities about the leaks for months.

“These are communities with deep roots in extractive processes like coal mining and natural gas, so developers coming in and proposing something is nothing new for them, but when they learn that developers are interested in not extracting but depositing, injecting, their eyes widen,” said Ethan Story, advocacy director and attorney at the Center for Coalfield Justice, a community health advocacy group in western Pennsylvania.

Fossil fuel partners

Each hydrogen hub has a corporate, nonprofit or public-private partnership organization that oversees the project. The partnership organization is in charge of putting together the proposal, selecting projects, facilitating engagement, receiving and distributing federal funding and acting as a liaison between the DOE and industrial partners. In addition to the $7 billion federal investment, funding for the hydrogen hubs will include substantial private investments, incentivized by the Inflation Reduction Act.

Some of the prime contractors existed prior to the hydrogen hubs launching, like Battelle, which is overseeing the Appalachian hub, and the Energy & Environmental Research Center, which is overseeing the Heartland hub. Others were formed specifically to oversee the hydrogen hub projects, like the Alliance for Renewable Clean Hydrogen Energy Systems (ARCHES), which is overseeing the California hub, and HyVelocity, Inc., which is overseeing the Gulf Coast hub.

In addition to these contractors, the hubs have individual project partners that include fossil fuel companies. In the Gulf Coast hub, Chevron, ExxonMobil and Shell are among the fossil fuel companies listed as project partners. The Appalachia hub’s partners include CNX Resources, Enbridge, Empire Diversified Energy and EQT Corporation; and the California hub lists Chevron among its partners.

This is creating distrust in some communities.

For example, in a DOE document released in August, the agency reported that EQT Corporation, the second-largest natural gas producer in the country, would host community listening sessions and work toward establishing a community advisory committee for its projects in the Appalachian hydrogen hub. EQT has racked up environmental violations at its fracking wells that caused multiple families in West Virginia to move out of their homes. The company has also promoted misinformation about the natural gas industry’s role in worsening climate change.

“Choosing EQT to run this part of the project shows the lack of real community engagement, the lack of community trust, the lack of community transparency that surrounds the [Appalachian hydrogen hub] community benefits process,” said Matt Mehalik, executive director of the Breathe Project, a coalition of clean air advocacy nonprofits in western Pennsylvania. “This choice of manager illustrates the lack of interest in establishing any sort of trust with impacted communities.”

Karen Feridun, a cofounder of the Better Path Coalition, a Pennsylvania climate advocacy group, said: “If EQT creates a [community advisory committee], it’ll be to find out what color ARCH2 [Appalachian hydrogen hub] baseball caps they prefer.”

EQT Corporation and Battelle did not respond to multiple requests for interviews, nor to specific questions about the community engagement process and the alleged lack of transparency.

The DOE also outsourced community engagement in the Gulf Coast to a local organization — the Houston Advanced Research Center, or HARC. The organization was founded in 1982 by George Mitchell, known as the “father of fracking,” who was credited for the shale boom in Texas. In 2001, HARC updated its mission on its website to reference mitigating climate risk and advancing clean energy, and in 2023 the organization included hydrogen energy in its strategic planning and company vision.

Community engagement representative and HARC deputy director of climate equity and resilience Margaret Cook said the organization had reached out to a few local advocacy groups to discuss its role in the hub’s community engagement. Cook said they plan to include a community advisory board that will interact with the companies involved and advise on how DOE dollars are spent at the community and regional levels. Additionally, the group will be tasked with organizing community benefits.

“We need to understand what their concerns are so that we can address them,” said Cook. “And we need to understand what they would perceive as a benefit that is actually going to help them, so that the project can do that.”

Shiv Srivastava, research and policy researcher for Fenceline Watch, a Houston-based environmental justice organization said: “I think that this is a fundamental problem … you have organizations that are chosen to basically be the community connector, the proxy for the hub with the community. This is something the Department of Energy should be doing directly.”

A lack of transparency and meaningful engagement

Some describe Houston’s East End as a checkerboard, where the borders of their homes, schools and greenspaces are marked by industrial plants, parking lots, entry docks, smokestacks and refineries.

The East End community is in the 99th percentile for exposure to air toxics and home to the state’s largest sources of chemical pollution. Residents of these neighborhoods, such as Srivastava and Yvette Arellano, executive director of Fenceline Watch, worry that this enormous industrial presence will only increase with the introduction of hydrogen.

“When it comes to things like carbon capture, sequestration, direct air capture, these are almost like supporting tenets for hydrogen,” Srivastava said. “We see hydrogen rapidly being posited as the new feedstock for petrochemical production, to displace fossil fuels, which, for our community, doesn’t work, because they’re just still continuing to produce these toxics [with hydrogen production].”

Arellano said that Fenceline Watch educates the public about industrial projects, but for hydrogen that’s been complicated by “the lack of a formalized community engagement process across all seven hubs.”

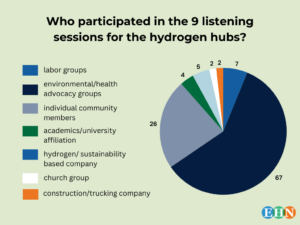

The DOE’s Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED) held nine initial listening sessions for the hubs and summarized the feedback received during those meetings on its website. The DOE did not make recordings of these meetings publicly available, but an analysis of the DOE’s transcripts shows that a majority of commenters voiced concerns about issues like employee safety, pipeline siting, carbon capture efficacy, emissions impacts, who will regulate these projects, permitting, site locations, language barriers and environmental injustice.

For the Gulf Coast Hub, the community asked for formalized sessions where they could write in questions and get written responses using simple language. “What we have heard is that this is not how this process goes,” Arellano said.” We have heard dead silence.”

Of the 113 comments the DOE transcribed from the listening sessions, 95 voiced some opposition to the projects, and calls for greater transparency and better community engagement were issued at least 49 times.

In response to complaints about engagement for the hubs, the DOE published a summary outlining key themes it heard during the listening sessions and how that feedback has been incorporated into the planning process for the hubs. An agency spokesperson said this type of community engagement is new for the DOE and the projects are all in early stages, so the agency is still learning and is working to ensure that community concerns are adequately addressed.

In response to complaints about engagement for the hubs, the DOE published a summary outlining key themes it heard during the listening sessions and how that feedback has been incorporated into the planning process for the hubs. An agency spokesperson said this type of community engagement is new for the DOE and the projects are all in early stages, so the agency is still learning and is working to ensure that community concerns are adequately addressed.

They added that the OCED has held more than 70 meetings with community members and groups, local elected officials, first responders, labor and other community groups, and has provided informational briefings to more than 4,000 people in the hydrogen hub regions.

“I have questions and concerns,” Democratic North Dakota state senator Tim Mathern said. “Thus far I support it as it is presented as a cleaner fuel than fossil fuels and better for our environment. Very little information is provided about the environmental impacts, and I would like to know more.”

EHN reached out to other policymakers in the 16 states with proposed hydrogen projects and received five responses, with four coming from states in proposed Pacific Northwest hydrogen hub regions. Most responses from policymakers noted a need for more information, similar to their constituents.

“There has been involvement with local officials in my area as well as some state officials,” Republican Montana state representative Denley Loge said. “Most (people) do not fully understand but do not dig deeper on their own. On the local level, when meetings have been held, few attend but rumors go rampant without good information.”

Democratic Texas state representative Penny Morales Shaw expressed support for the Gulf Coast hub: “As a state representative, I receive feedback from my constituents every day about poor air quality and environmental conditions impacting their health and quality of life,” Morales Shaw said. “Hydrogen hubs can help bring us to net-zero carbon emissions, and we all want to make sure it’s done in an effective, collaborative way.”

The listening sessions are just one way communities have requested improvements to the DOE’s engagement process. Written requests made to DOE regarding transparency around the hydrogen hubs outside of the listening sessions showed the following:

- A group of leaders from numerous national advocacy groups, including Clean Air Task Force, the Environmental Defense Fund and the Natural Resources Defense Counsel, also formally asked the DOE for increased transparency and engagement around the hydrogen hubs.

- 54 Appalachian organizations and community groups signed a letter to the DOE calling for the suspension of the Appalachian hub, citing a lack of transparency and engagement.

- 32 groups from the Mid-Atlantic hub region signed a letter to the DOE stating that the first public meeting on the hub was inaccessible to many residents and requesting increased transparency and engagement.

- 15 community groups from the Midwest hydrogen hub region sent the DOE a letter expressing frustration over the lack of transparency and engagement.

- Nine environmental and justice advocacy groups in California made similar requests related to transparency and engagement.

- A coalition of groups from Texas, California, Washington, Pennsylvania, New Mexico and Indiana requested improved transparency and engagement around hydrogen energy in a published report.

- In the absence of meaningful engagement on the projects, a coalition of advocacy groups also recently published their own “Guide to Community Benefits in Southwestern Pennsylvania” with the hopes that the Appalachian hydrogen hub project, and others like it, will use it as a reference.

A DOE spokesperson said the agency has responded directly to more than 50 letters, but most of those responses have not been made public. Community advocates who received responses to these letters said they were dissatisfied. The agency declined to answer questions about whether it was working to meet the specific requests in these letters.

In initial presentations about the hubs, the DOE discussed “go/no-go” stages for the projects, which require community engagement before the projects can move forward. This led many community members to believe this meant the projects could be stopped if communities decided the costs outweigh the benefits. That turned out not to be the case.

“Communities will not have a direct right of refusal,” DOE said in an emailed response to questions from community groups about the Mid-Atlantic hub in July. “This is not a requirement of the H2Hubs program.”

Some people, including Feridun of the Better Path Coalition in Pennsylvania, felt misled. “We’ve been fed a line over and over about these go/no-go decisions and how we’ll be engaged when each one is being made, but that’s simply not what’s happening,” Feridun said.

Advocates question the ethics of the federal government citing new pollution sources in environmental justice communities whether or not they consent to it.

There’s also a widespread perception that the hubs’ industrial partners are forging ahead with planning in closed-door meetings with agency officials, without community input.

“The DOE appeared on the very first listening session as a co-host of the call with [the industrial partners],” Chris Chyung, executive director of the environmental advocacy group Indiana Conservation Voters, speaking about the Midwest Hydrogen hub. “It creates an ethical dilemma since DOE is supposed to be a mediator, providing oversight of this money and advocating on behalf of the taxpayers who are funding it.”

On the East Coast, the prime contractor leading the Mid-Atlantic hub set up monthly networking meetings for corporate partners that cost $25-$50 to join and were not open to the public. It also established a tiered membership program that cost between $2,500 and $10,000 and gave members free access to educational webinars, free registrations for an “annual MACH2 Hydrogen Conference,” and access to members-only events and a members-only online portal with additional information about the projects.

In an email to local advocates who asked why these opportunities weren’t open to the public, a DOE spokesperson said the networking meetings were “for businesses, startups and other parties engaged in the clean energy economy” and “are not intended to be a substitute for community events.”

“Our biggest concern is that many projects that are already set as key components to [the Mid-Atlantic hydrogen hub] are being advanced with no community outreach,” said Tracy Carluccio, deputy director of the Delaware Riverkeeper Network. The nonprofit Carluccio heads filed a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to gain access to these applications and other materials related to the Mid-Atlantic hydrogen hub in November 2023. When they received responses in August 2024, they learned that numerous projects were further along in the planning process than they’d realized.

Similarly, near the California and the Pacific Northwest hubs, communities have heard promises that hydrogen production will only come from renewables, according to Kayla Karimi, a staff attorney for the California-based nonprofit Center on Race, Poverty and the Environment. Her organization has not seen any contracts or documents supporting those promises beyond the initial announcements made prior to funding.

Karimi said that her organization was asked to sign a non-disclosure agreement (NDA) to obtain information about the California hub beyond what’s on its website. She found the NDA “very punitive” and said those who signed it could face legal ramifications for speaking negatively about the California hub. Karimi’s organization did not sign the NDA, and advocated against community members doing so.

Steven Lehat, managing director of the investment banking company Colton Alexander, did agree to sign NDAs to gain access to three otherwise-private planning committees for the California hub. While the NDA provided more information, that information legally could not be shared with community members. Barriers like these raised the question of how equitable the community engagement process is, even for the hubs that are slated to use mainly renewable energy sources.

“The community’s comments thus far have been really limited because we don’t know what we’re commenting on,” Karimi said. “But also we wouldn’t know if they’re being incorporated whatsoever, because we haven’t been told anything [and] have not been communicated with.”

When asked about the NDA’s, a spokesperson for ARCHES, the organization managing California’s hydrogen hub, said that NDAs were not required in order to join workgroups related to community engagement or benefits.

“ARCHES stands by our principle of being stakeholder and community engaged and will continue to work to ensure that all stakeholders can participate in our community meetings,” the spokesperson said in an email. “However, NDAs are necessary for becoming an ARCHES member, as member companies must feel confident sharing sensitive or proprietary information.”

The Pacific Northwest hub was distinct in having public information available compared to the other six hubs. Keith Curl Dove, an organizer with Washington Conservation Action, said his organization was able to access proposed project locations and tribal outreach history, and said that the Washington Chamber of Commerce attempted to respond to all questions and concerns that his organization had.

Policymakers in Washington mirrored Dove’s perspective.

“I will say, I feel like there has been a pretty broad stakeholder engagement process, which is different than a community engagement process, early on to figure out which businesses, which industries, etc., were going to be ready to make the investments to match Washington state’s and the federal investment in our [Pacific] Northwest hydrogen hub,” said Democratic Washington state representative Alex Ramel.

“Two of the state’s five refineries are in my district, and two more are in the next district, north of me,” Ramel said. “So about 90% of the state’s refining capacity is right next door, and the refineries are going to be a major place where hydrogen is deployed in Washington State, and I think they’re an important early customer… because they’re already using dirty hydrogen, and this is a chance to replace it with green hydrogen.”

In US Environmental Protection Agency documents, the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council shared concerns about hydrogen hubs and other carbon management technologies, stating, “This investment in ‘experimentation’ of technology that lacks sufficient research of both its safety and efficacy further creates barriers of distrust between impacted communities, particularly those who have been historically and currently disenfranchised, and the respective government agencies.”

The Council added that “a humane approach to carbon management would be to prioritize sound research (not influenced by polluters) that includes a robust focus on potential public health and environmental risks.”

These concerns mirror those of individuals working on the ground.

“Can we really rely on another potential polluter?” asked Arellano of Fenceline Watch.

Read Part 2 tomorrow: What’s hampering federal environmental justice efforts in the hydrogen hub build-out?

————————————–

Author bios:

Kristina Marusic covers environmental health and justice issues in Pittsburgh and Western Pennsylvania for Environmental Health News. Her new book, “A New War On Cancer: The Unlikely Heroes Revolutionizing Prevention,” uncovers an emerging national movement to prevent cancer by reducing our exposure to cancer-causing chemicals in our everyday lives.

Cami Ferrell is a bilingual video reporter for Environmental Health Sciences based in Houston, Texas. Ferrell primarily reports on the petrochemical buildout in the Texas Gulf Coast.

(Featured image compilation of photos by Kristina Marusic and Jennifer Gazdick for Just Transition Northwest Indiana.)

EWG

EWG