Postcard from California: Climate change is fueling faster-spreading, more extreme wildfires

This summer, the Park Fire burned more than 425,000 acres near Chico, Calif. – the fourth-largest wildfire in the state’s history. It started when an arsonist pushed a flaming car into a grassy, brush-strewn gully, sparking California’s largest-ever deliberately set wildfire. But what set the Park Fire apart from the 7,194 wildfires that have burned more than 1 million acres in California this year was how fast it grew.

After first igniting on July 24, it spread an estimated 5,000 acres an hour – about one football field a second. In 24 hours it burned 150,000 acres, and in 72 hours incinerated an area larger than San Francisco. Fire experts said it was among the fastest-growing wildfires in history.

As it burned, Zeke Lunder, director of Deer Creek Resources, a wildfire management consulting firm in Chico, told The Washington Post that in 25 years of mapping large fires throughout the Western US, he couldn’t recall another blaze that spread so far so fast. He said the Park Fire “was moving in ways we aren’t used to seeing.”

It’s settled science that the climate crisis is increasing the number and frequency of wildfires. A 2016 study estimated that from 1984 to 2015, human-caused climate change contributed to the burning of almost twice the acreage in 11 Western states than might have burned in its absence.

Now, new research confirms that Western wildfires are also spreading faster.

In a study published Oct. 24 in the journal Science, a team of researchers analyzed images from NASA satellites to track the day-by-day spread of more than 60,000 fires in the continental US from 2001 to 2020.

They found that in that period, the average peak daily growth rate of wildfires in the West more than doubled. In California, wildfires spread almost four times as fast in 2020 as in 2001. They cited other research predicting that if global warming continues at its current pace, the frequency of the fastest-spreading fires in the West could double in 30 years.

“The modern era of megafires is often defined based on wildfire size, but it should be defined based on how fast fires grow,” the researchers wrote. “Speed fundamentally dictates the deadly and destructive impact of megafires… [F]ire speed matters more for infrastructure risk and evacuation planning.”

They cited the 2018 fire that wiped out the town of Paradise, Calif., in which 85 people died because there was only one route to escape the rapidly spreading flames.

“We’ve been so focused on size, but what we really need to focus on is speed,” Jennifer Balch, the study’s lead author and an associate professor of geography at the University of Colorado at Boulder, told The New York Times. A co-author, University of California at Los Angeles geography professor Park Williams, told the Los Angeles Times: “The faster the fire, the more easily it can escape control.”

That’s intuitive. But Williams said recent developments in satellite technology allowed the team to quantify the relationship between how fast fires spread and how much damage they cause: A tiny fraction of the fastest-moving fires analyzed – less than 3% – did more than three-fourths of the total property damage.

Conditions in Chico on July 24 were what Californians call “fire weather:” A high of 108 degrees Fahrenheit, no measurable rain for months, winds gusting to almost 30 miles per hour. But the next day, as the Park Fire raged through bone-dry oak and manzanita brush, it did something fire watchers are seeing more often: It created its own weather.

Swirling clouds of smoke, ash and embers rose to 30,000 feet and formed a spinning vortex of flame known as a “fire tornado.” Its winds propelled burning firebrands far ahead of the tornado’s eye, spreading the inferno by leaps and bounds.

The most extreme fire tornadoes can generate thunderstorms, hail and lightning. They were virtually unknown, or at least unrecorded, until the Australian “Black Saturday” bushfires of 2003, when an astonished citizen caught one on video.

But in recent years, they’ve been documented several times in California, including during the Carr Fire of 2018, the Creek and Loyalton fires of 2020, and the Tennant Fire of 2021. The Carr Fire tornado, whose winds reached 143 miles per hour, is considered the strongest tornado of any kind in the state’s history.

“Fire Weather: On the Front Lines of a Burning World” is journalist John Vaillant’s chilling account of the wildfires that in 2016 ravaged the city of Fort McMurray in Alberta, Canada. He writes that fire tornadoes “have become significantly more common over the past two decades, occurring around the world, in places they have never been observed before.”

“Fires are now making their own behavior,” Jonathan Cox, a deputy chief of California’s state firefighting agency, told Vaillant. “The anomalies are becoming more frequent and more deadly.” Of the Carr Fire, he said, “We’ve never seen anything like this. ‘Extreme’ is an understatement.”

The climate crisis is not the only factor in the increase in faster, more intense wildfires.

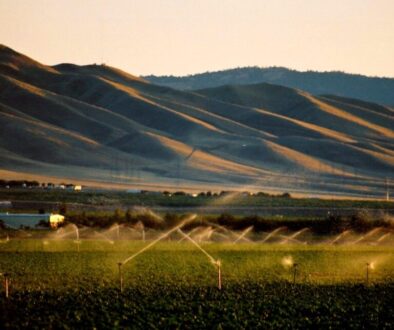

Particularly in the West, millions of Americans have moved to what’s called the Wildland-Urban Interface, where residential subdivisions abut forests that drought and mismanagement have turned to tinderboxes. These houses, unlike those of earlier generations, are packed with highly flammable plastics and other materials that can cause a house to be leveled by fire in minutes.

But the warmer, drier climate, and the plastics made from oil and gas, are the products of our dependence on fossil fuels and our stubborn resistance to curb our addiction to them.

As Vaillant’s book concludes: “This is not Planet Earth as we found it. This is a new place – a fire planet we have made.”

- Bill Walker has more than 40 years of experience as a journalist and environmental advocate. He lives in California’s San Joaquin Valley.

(Opinion columns published in The New Lede represent the views of the individual(s) authoring the columns and not necessarily the perspectives of TNL editors.)

(Featured photo by Casey Horner on Unsplash+.)

November 16, 2024 @ 2:24 pm

Wildfires are burning and spreading faster because the ground and vegetation are full of aluminum oxide from the aerial spraying that is heavily used in California. They’re spraying everything from the air with incendiary chemicals!

“Climate Change” is a hoax. These fires and other weather disasters are a result of humans geoengineering the weather:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A24fWmNA6lM

http://www.goeengineering.org