What’s hampering federal environmental justice efforts in the hydrogen hub build-out?

By Kristina Marusic and Cami Ferrell

This is part 2 of a 2-part series originally published at Environmental Health News. Read part 1: Hydrogen hubs test new federal environmental justice rules

One Wednesday evening last May, Yukyan Lam stared into the camera on her computer, delivering carefully prepared remarks during a virtual listening session convened by the US Department of Energy (DOE).

The goal of the event was for the federal agency to hear concerns and questions from communities that could be impacted by the Mid-Atlantic hydrogen hub, one part of a massive federal program working to establish a national hydrogen energy network.

Lam, the director of research at The New School’s Tishman Environment & Design Center, had just three minutes to present research on a wide range of potential health impacts associated with carbon capture and storage and hydrogen energy deployment, including increased rates of respiratory issues, premature mortality, cardiovascular events, and negative birth outcomes. Later, after reading the DOE’s public summary of the event, she felt frustrated.

“I didn’t feel like they accurately summarized the research I shared, or that the DOE really heard or valued what was said in the listening session,” Lam said. “They’re moving these projects forward but they haven’t meaningfully engaged with communities yet.”

Lam, who had been providing research and technical assistance to the New Jersey Environmental Justice Alliance, a nonprofit following the development of the hub, wasn’t alone in her frustration.

The Mid-Atlantic hub is one of seven proposed, federally funded networks of infrastructure — an initiative borne from the Biden administration’s 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law — that aim to use both renewable and fossil fuel energy to create hydrogen for energy use by heavy industries that are difficult to electrify like steelmaking, construction and petrochemical production. The hubs support the administration’s objective of reaching net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 and achieving a 100% clean electrical grid by 2035.

In 2023, the Biden administration passed historic federal policies directing 80 agencies to prioritize environmental justice in decision-making. The DOE pledged to lead by example with the seven new hydrogen hubs, but impacted communities across the country say that just isn’t happening.

In interviews, more than 30 community members and dozens of organizations in the regions where the hydrogen hubs are planned said that details of the projects remain hazy, public input is only planned after industry partners have received millions of dollars in public funding, and communities feel that they have no say in the decision-making.

Community members have also expressed concerns about the alleged climate benefits and potential pollution from the hubs.

“This hydrogen hub is just one piece of this larger picture about the US’s carbon management strategy,” Lam said. “These technologies are risky, with a lot of potential to cause health harms in environmental justice communities, and they also don’t work particularly well… If they were a great climate solution we still wouldn’t be on board if it was unjust, but the fact is that carbon capture is not even a great climate solution.”

Experts say evolving federal regulations and well-intentioned but hard-to-implement federal environmental justice initiatives are keeping communities in the dark. They also say including communities in the early stages of project development isn’t just about advancing environmental justice — it’s also about efficiency.

“Studies have shown that when you meaningfully engage communities on the front end of a project, it results in less litigation and quicker finalization times,” said Chris Espinosa, legislative director for climate and energy at Earthjustice, a nonprofit legal advocacy group.

NEPA unknowns

Under the National Environmental Policy Act (commonly referred to as NEPA), federal agencies are required to assess the environmental and health impacts of proposed development projects, disclose those findings to the public and provide opportunities for public engagement. But the specifics of how that works varies across agencies.

“There are ways to do this really well,” Espinosa said, “but there are also ways to just do the required steps and check the boxes that aren’t really going to produce the tangible outcome of having communities’ input, concerns and aspirations reflected in the end product.”

A year into the hydrogen hub projects, it’s still unclear which state and federal agencies may be involved and what types of public engagement will be required.

“How exactly NEPA is going to be applied depends very much on what the project is, and we don’t know that without the transparency these communities have been asking for,” Espinosa said. “There are also many ways federal agencies can go above and beyond what’s required by NEPA… but so far the Department of Energy has done none of those things.”

Complicating things further, many of NEPA’s key provisions were gutted under the the Trump administration, but then restored and expanded by the Biden administration, leaving federal agencies scrambling. And the Biden administration’s separate environmental justice initiatives gave federal agencies additional new mandates. With Trump returning in January, agencies will likely experience more regulatory whiplash.

One challenge with the hydrogen hubs is that NEPA-mandated public engagement opportunities are planned, but not until after funding has already been awarded to industrial partners — at which point community members fear their input will be irrelevant.

“The DOE keeps saying to wait until awards have been announced and then there will be more engagement opportunities,” said Ben Inskeep, a program director for the nonprofit Citizens Action Coalition of Indiana who is concerned about the Midwest hydrogen hub. “But that’s setting these projects in motion before asking communities to weigh in, rather than involving us from the start to determine whether the projects are appropriate and will work for us.”

The Appalachian and California hubs both received $30 million and the Pacific Northwest hub received $27.5 million in initial funding from the federal government in July. Funding for the other four hubs is still being processed. In total, the seven planned hydrogen hub projects are slated to receive $7 billion in federal funding.

Federal environmental justice efforts

Experts involved with the planning process for the hydrogen hubs said the DOE asked consultants for help incorporating the tenets of the proposed national Environmental Justice for All Act, which is considered the “gold standard” for community engagement.

The agency incorporated those strategies into its directives for community benefit plans for the hubs, which are plans industrial partners have to develop when applying for funding.

The directives include recommendations to “engage early with methods that are not a formal process,” and facilitate “discussion of whether there is a pathway for the project to propose multiple sites or consider changing the proposed site based on project learnings from engagement.” It also states that effective engagement “should allocate sufficient time for relationship building, incorporating or responding to input, sharing the results of engagement with the community, and any plans for negotiating formal agreements with labor and community partners.”

“This document seems like a great model for how to do this all right,” said Lauren Piette, a senior associate attorney for Earthjustice’s clean energy program. “The problem is we’re just not seeing any of it done yet.”

DOE said it would provide summaries of the community benefits plans on its website for “transparency and accountability,” but it has yet to do so for six out of the seven hubs, with the exception of the California hub, which was required to publish its community benefits plan under state law.

For the other hubs, none of the community groups interviewed had been invited to participate in discussions about community benefit plans with industry partners or the DOE. The publicly available materials related to community benefits plans reference jobs and economic benefits. There’s little to no mention of monitoring new air pollution sources or minimizing public health impacts, bolstering local emergency services in case of leaks or explosions, or ongoing assessments of the climate, economic and environmental health costs and benefits for the projects, all of which residents have requested. The DOE has declined to share how it’s assessing the strengths and weaknesses of those plans.

“It’s all smoke and mirrors,” said Karen Feridun, a Pennsylvania-based environmental activist who leads a national hydrogen hub working group. “The hubs have not been engaging communities. Every decision that has been made has been made behind closed doors.”

The DOE did not respond to questions about how the hydrogen hub projects advance the climate and environmental justice objectives of the Biden administration, whether there are mechanisms in place for incorporating community feedback into the planning process, or whether the agency has adjusted the community engagement and/or decision-making process for any of the hydrogen hub projects based on requests from members of potentially impacted communities.

Federal limitations in pursuing community engagement

There’s a widespread perception among both community members and experts that the DOE is well-intentioned but lacks the tools and infrastructure to live up to its community engagement promises. The DOE’s Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED) was created in December 2021 with a budget of $25 billion, and the agency is charged with distributing up to $7 billion for the hydrogen hubs.

“This is a brand new office that’s still trying to figure out its mandates and internal processes and has been given a massive budget, and it takes time to be successful — in fact, I’d be surprised if it went smoothly from the get-go,” said Darshan Karwat, an associate professor of engineering at Arizona State University who researches engineering ethics and environmental justice, and who previously worked at the DOE. “Three years is not enough time to establish an office, figure out a funding process, go through all the bureaucratic and legal requirements, then do community engagement work — which itself takes a significant amount of time — and then distribute this huge budget on these projects.”

The Biden administration’s environmental justice directives also represent a major shift in priorities for the DOE, which “has been set up to maximize other values and prioritize technological and economic metrics,” Karwat said. “It would be difficult for it to do a good job at aligning with new kinds of values without the appropriate time to create buy-in at all levels of the agency. Organizational change in large bureaucracies takes time.”

To help address that, Karwat received funding from the DOE Water Power Technologies Office and Office of Energy Justice and Equity to develop tools for assessing how well the agency is meeting its environmental justice goals, and approaches to embed environmental justice into DOE programs and processes. Details about how to use the tool were published alongside a case study in a paper in 2023 with new work ongoing, but as far as Karwat knows, the tool is not being used for the hydrogen hub projects. “Please let them know we’d be happy to help them with this,” he said.

People across the country said the lack of transparency and meaningful community engagement for the hydrogen hubs seems to be at odds with the Biden administration’s stated commitments to environmental justice.

“I don’t think the president is aware that his environmental justice priorities are being ignored for the [Midwest hydrogen hub] proposal,” said Chris Chyung, executive director of the environmental advocacy group Indiana Conservation Voters.

Jalonne White-Newsome, federal chief environmental justice officer at The White House Council on Environmental Quality, pointed to several measures that are meant to ensure that federal agencies are complying with the spirit of Biden’s executive order on environmental justice, rather than just checking the necessary boxes. She said the order requires the development of agency-specific strategic plans to advance environmental justice and plans to assess them along the way, “so it’s not just going to be words on a paper that nobody looks at and just shelves.”

White-Newsome also pointed to the establishment of the Environmental Justice Interagency Council, which brings together representatives from different agencies who are “committed to making sure that what is in the executive order, the initiatives that the president is driving, are actually operationalized.”

What happens next?

The three hubs that have received federal funding — the Appalachian, California and Pacific Northwest hubs — have begun “phase 1” of the development process, during which they’re expected to advance planning, development and design for hub components; begin deploying technology; and do additional community benefits planning and community engagement, according to the DOE. Additional opportunities for community engagement have been announced for some of these hubs.

California’s hub proclaimed itself as the first to officially launch on Aug. 30 of this year. If there are no construction, legal or governmental roadblocks, the hub could be complete in eight to 13 years, according to OCED projections. The Appalachian and Pacific Northwest hubs are also expected to take around a decade to complete after they officially launch — along with billions of dollars in private investment and additional public funding from tax breaks.

For the remaining four hubs, additional community engagement opportunities aren’t expected until the first round of federal funding has been distributed.

The hydrogen hubs and other clean energy projects will look different in the new year when Donald Trump is president again. Even if funding for the hubs remains untouched, public engagement requirements could change, as Trump has already gutted NEPA once and has promised to undo environmental regulations on the campaign trail. As president, Trump rolled back more than 100 environmental regulations, some of which took nearly all of Biden’s four years as president to reinstate.

While the fate of the hydrogen hubs could be determined by changes under the incoming Trump administration, community advocates aren’t waiting to take action.

“I would want the Department of Energy and the federal government to interact with our communities in the manner in which they interact with industry,” said Shiv Srivastava, research and policy researcher for Fenceline Watch, a Houston-based environmental justice organization. “DOE has had a hydrogen moon shot for a very long time, and they’ve been working very closely with their industry partners. Where are the community partners? Outreach looks like what they start doing decades prior with industry, because they have a concerted effort.”

Virginia Wiltshire-Gordon, the community engagement manager for Pipeline Safety Trust, a national nonprofit that promotes pipeline safety and transparency, said: “I think the main thing is that the Department of Energy needs to do more work to meet community members where they are. So that means doing education. It means thinking about who’s trusted sources in the community and connecting with people.”

White-Newsome, the federal chief environmental justice officer at The White House, encouraged community members who are frustrated with the process to reach out to the White House’s Council on Environmental Quality.

“We have an open door,” White-Newsome said. “If there are conversations that communities are not able to have, or not able to connect, or don’t feel satisfied about with some of our agency partners, it is [the Council on Environmental Quality’s] role to help intervene where possible.”

“While I have not heard from constituents directly about the hydrogen hubs, I do recognize concerns regarding the use of hydrogen and issues such as the cost, efficiency, sustainability and water usage to name a few,” Oregon state representative John Lively said. “The project is still early in the process and any project in Oregon will need diverse community engagement to succeed. I will work with constituents and I urge the federal government, as they move forward, to seriously engage with local constituents, stakeholders, activists and leaders.”

Robert Routh, a policy director at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), said that despite the challenges so far, he hopes communities won’t give up on fighting for meaningful engagement around the hubs.

“This will play out over the course of the next decade, so we’re still in a window of time here where both federal agencies and project partners can and must make improvements,” Routh said. “Even though we’re a year in with less engagement and transparency than we’d like, I hope community members don’t feel like it’s too late for their input to make a difference.”

Video production and editing: Jimmy Evans

Kristina Marusic covers environmental health and justice issues in Pittsburgh and Western Pennsylvania for Environmental Health News. Her new book, “A New War On Cancer: The Unlikely Heroes Revolutionizing Prevention,” uncovers an emerging national movement to prevent cancer by reducing our exposure to cancer-causing chemicals in our everyday lives.

Cami Ferrell is a bilingual video reporter for Environmental Health News based in Houston, Texas. Ferrell primarily reports on the petrochemical buildout in the Texas Gulf Coast.

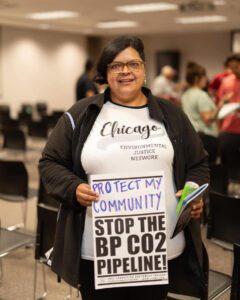

(Featured image photos by Fred Stine of Delaware Riverkeeper Network; Kristina Marusic for EHN; and Ray Bailey.)

EWG

EWG