Postcard from California: Why the ‘Erin Brockovich’ Chemical Is Still Unregulated

By Bill Walker

In 2001, California lawmakers passed a law requiring the state to set a legal limit for a cancer-causing chemical found in the tap water of more than 9 in 10 Californians called chromium-6. The legislation was spurred by the film “Erin Brockovich,” based on the true story of a small town’s David-and-Goliath battle against the state’s largest utility over contamination of its water supply.

The law ordered establishment of a health-protective standard for chromium-6 in drinking water by 2004. But nearly 20 years after that deadline, the process is still unfinished.

What’s worse, the weak standard recently proposed by the State Water Resources Control Board would leave millions of Californians at increased risk of cancer. And more than a decade after a US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) toxicological review concluded that chromium-6 in drinking water is a likely human carcinogen – a finding reaffirmed last year – there is still no federal standard to protect Americans nationwide.

The tortuous story of California’s long delay and the EPA’s inaction on chromium-6 shows how hard it is to regulate hazardous industrial chemicals in the US. It takes far too long, and a big reason is that polluting industries can stall the process with shady tactics.

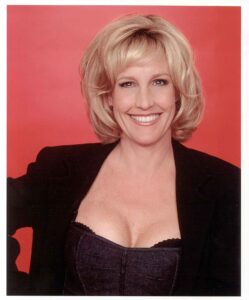

In 1993, investigating unexplained illnesses in Hinkley, Calif., for a Los Angeles law firm, Brockovich uncovered decades of chromium-6 dumping by Pacific Gas and Electric Co. (PG&E). Her firm sued PG&E on behalf of the town, and in 1996 the utility settled out of court for a then-record $333 million. The film based on the case won an Academy Award for Julia Roberts in the title role in 2001.

That same year, the state asked the University of California (UC) to convene an expert panel to assess the chemical’s health hazards. It was well-established that breathing chromium-6 fumes causes lung cancer – the reason California banned its use in chrome plating earlier this year – but there were few human studies of the risks the chemical posed in drinking water. Citing an obscure Chinese study, the panel’s report said a drinking water standard was not needed.

EWG

EWG